WWF’s Secret War

WWF Funds Guards Who Have Tortured And Killed People

The World Wide Fund for Nature funds vicious paramilitary forces to fight poaching. A BuzzFeed News investigation reveals the hidden human cost.

Tim Lane / Guy Shield for BuzzFeed News

Down the road from the crocodile ponds inside Nepal’s renowned Chitwan National Park, in a small clearing shaded by sala trees, sits a jail. Hira Chaudhary went there one summer night with boiled green maize and chicken for her husband, Shikharam, a farmer who had been locked up for two days.

Shikharam was in too much pain to swallow. He crawled toward Hira, his thin body covered in bruises, and told her through sobs that forest rangers were torturing him. “They beat him mercilessly and put saltwater in his nose and mouth,” Hira later told police.

The rangers believed that Shikharam helped his son bury a rhinoceros horn in his backyard. They couldn’t find the horn, but they threw Shikharam in their jail anyway, court documents filed by the prosecution show.

Nine days later, he was dead.

Hira Chaudhary

Tsering Dolker Gurung for BuzzFeed News

An autopsy showed seven broken ribs and “blue marks and bruises” all over his body. Seven eyewitnesses corroborated his wife’s account of nonstop beatings. Three park officials, including the chief warden, were arrested and charged with murder.

This was a sensitive moment for one of the globe’s most prominent charities. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) had long helped fund and equip Chitwan’s forest rangers, who patrol the area in jeeps, boats, and on elephant backs alongside soldiers from the park’s in-house army battalion. Now WWF’s partners in the war against poaching stood accused of torturing a man to death.

WWF’s staff on the ground in Nepal leaped into action — not to demand justice, but to lobby for the charges to disappear. When the Nepalese government dropped the case months later, the charity declared it a victory in the fight against poaching. Then WWF Nepal continued to work closely with the rangers and fund the park as if nothing had happened.

As for the rangers who were charged in connection with Shikharam’s death, WWF Nepal later hired one of them to work for the charity. It handed a second a special anti-poaching award. By then he had written a tell-all memoir that described one of his favorite interrogation techniques: waterboarding.

Shikharam’s alleged murder in 2006 was no isolated incident: It was part of a pattern that persists to this day. In national parks across Asia and Africa, the beloved nonprofit with the cuddly panda logo funds, equips, and works directly with paramilitary forces that have been accused of beating, torturing, sexually assaulting, and murdering scores of people. As recently as 2017, forest rangers at a WWF-funded park in Cameroon tortured an 11-year-old boy in front of his parents, the family told BuzzFeed News. Their village submitted a complaint to WWF, but months later, the family said they still hadn’t heard back.

People living near Nepal’s Chitwan National Park

Tsering Dolker Gurung for BuzzFeed News

WWF said that it does not tolerate any brutality by its partners. “Human rights abuses are totally unacceptable and can never be justified in the name of conservation,” the charity said in a statement.

But WWF has provided high-tech enforcement equipment, cash, and weapons to forces implicated in atrocities against indigenous communities. In the coming days, BuzzFeed News will reveal how the charity has continued funding and equipping rangers, even after higher-ups became aware of evidence of serious human rights abuses.

A yearlong BuzzFeed News investigation across six countries — based on more than 100 interviews and thousands of pages of documents, including confidential memos, internal budgets, and emails discussing weapons purchases — can reveal:

- Villagers have been whipped with belts, attacked with machetes, beaten unconscious with bamboo sticks, sexually assaulted, shot, and murdered by WWF-supported anti-poaching units, according to reports and documents obtained by BuzzFeed News.

- The charity’s field staff in Asia and Africa have organized anti-poaching missions with notoriously vicious shock troops, and signed off on a proposal to kill trespassers penned by a park director who presided over the killings of dozens of people.

- WWF has provided paramilitary forces with salaries, training, and supplies — including knives, night vision binoculars, riot gear, and batons — and funded raids on villages. In one African country, it embroiled itself in a botched arms deal to buy assault rifles from a brutal army that has paraded the streets with the severed heads of alleged “criminals.”

- The charity has operated like a global spymaster, organizing, financing, and running dangerous and secretive networks of informants motivated by “fear” and “revenge,” including within indigenous communities, to provide park officials with intelligence — all while publicly denying working with informants.

World Wildlife Fund activists demonstrate on the sidelines of the UN Climate Change conference

Jorge Silva / Reuters

WWF has launched an “independent review” led by human rights specialists into the evidence uncovered by BuzzFeed News. “We see it as our urgent responsibility to get to the bottom of the allegations BuzzFeed has made, and we recognize the importance of such scrutiny,” the charity said in a statement. “With this in mind, and while many of BuzzFeed’s assertions do not match our understanding of events, we have commissioned an independent review into the matters raised.” The charity declined to answer detailed questions sent by BuzzFeed News.

It continued: “We hope that an accurate picture of our conservation work on the ground, the challenges faced by all, in some of the most dangerous and hostile places on Earth, and the efforts being made to secure a future for people and planet can be reflected in the story.”

WWF was established by a small group of mostly British naturalists in Zurich in 1961. Since then it has expanded globally, establishing field offices in over 40 countries, which are coordinated and led by executives at its international headquarters in Gland, Switzerland. It aims to “protect the future of nature,” a vital mission that has galvanized millions of supporters, including famous patrons, from Leonardo DiCaprio to Prince Charles to Sir David Attenborough. The charity’s advertising campaigns, many of which promote rangers as “one of the planet’s first and last lines of defense” against wildlife crime, inspire small donors to give in droves. In 2017 alone, WWF raked in more than 767 million euros, more than half of which came from members of the public.

“Some types of torture are done to obtain confessions, as the killing of a rhino is a very serious case.”

The charity funnels large sums of cash to its field offices in the developing world where staff work alongside national governments — including brutal dictatorships — to help maintain and police vast national parks that shelter endangered species. It says it is active in more than 100 countries on five continents, and showcases its collaborations with communities, whether in protecting reefs in the Pacific islands or facing off against illegal gold mining in the Amazon rainforest.

But many parks are magnets for poachers, and WWF expends much of its energy — and money — in a global battle against the organized criminal gangs that prey on the endangered species the charity was founded to protect.

It’s a crusade that WWF refers to in the hardened terms of war. Public statements speak of “boots on the ground,” partnerships with “elite military forces,” the creation of a “Jungle Brigade,” and the deployment of “conservation drones.” The charity sells forest ranger children’s dolls for $75, branded as “Frontline Heroes.”

WWF is not alone in its embrace of militarization: Other conservation charities have enlisted in the war on poaching in growing numbers over the past decade, recruiting veterans from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to teach forest rangers counterinsurgency techniques and posting promotional materials showing armed guards standing at attention in fatigues and berets. Ex–special forces operatives promote their services at wildlife conferences. But WWF stands out as the biggest global player in this increasingly crowded space.

The enemy is real, and dangerous. Poaching is a billion-dollar industry that terrorizes animals and threatens some species’ very existence. Poachers take advantage of regions ravaged by poverty and violence. And the work of forest rangers is indeed perilous: By one 2018 estimate, poachers killed nearly 50 rangers around the world in the previous year. But like any conflict, WWF’s war on poaching has civilian casualties.

Nepali army personnel burn wildlife parts seized from poachers at Chitwan National Park

AFP / Getty Images

Indigenous people living near one park in southeast Cameroon described a litany of horrors in interviews and documents obtained by BuzzFeed News: dead-of-night break-ins by men wielding machetes, rifle butt bludgeonings, burn torture involving chilis ground into paste, and homes and camps torched to the ground.

Their tormentors in these accounts were not poachers, but the park officials who police them. Although governments employ the rangers, they often rely on WWF to bankroll their work. Rangers are scattered thousands of miles apart across many countries, but WWF’s international network of offices effectively stitches them together into one global force fighting under the same set of principles.

Staffers in the charity’s in-country field offices are supposed to report any allegations of brutality back to its headquarters in Switzerland. But documents reveal WWF’s own staffers on the ground are often deeply entwined with the rangers’ work — coordinating their operations, jointly directing their raids and patrols alongside government officials, and turning a blind eye to their misdeeds.

Since 1872, when Native American tribes were forced to leave their ancestral lands to make way for Yellowstone National Park, hundreds of thousands of people worldwide have lost access to their land to ensure animals roam in people-free spaces. These communities, from the Tharu in Nepal to the Baka in Central Africa, remain on the outside looking in at land where their ancestors gathered food, built shelter, and made medicine out of natural resources for generations.

With deep knowledge of the land and its animals, these communities should be ideal partners in WWF’s war against poaching, anthropologists and activists said. Alienating locals only encourages them to assist professional out-of-town poachers, making that battle harder. “The Baka are the eyes and ears of the forest and could really help conservation,” said Charles Jones Nsonkali, a Cameroonian indigenous rights activist. “But they are treated as the enemy instead.”

A Baka woman fishes in the forest near Lobéké National Park

Tom Warren / BuzzFeed News

WWF said it does not see indigenous communities as its target: The goal is to catch organized criminals, not people struggling to feed their families. The charity vows to work hand in hand with these communities, and even has a written policy pledging that it will “not undermine” their human rights.

Yet, time and again, indigenous groups — both small-fry hunters and innocent bystanders — say they suffer at the hands of the rangers.

This is the untold story of collateral damage in WWF’s secret global war.

A sign near an entrance to Chitwan

Tsering Dolker Gurung for BuzzFeed News

On his knees outside Chitwan’s jail, Shikharam Chaudhary begged his wife, Hira, to get him out before it was too late. “He had told me crying that they might kill him if I cannot take him away,” Hira later told human rights investigators.

But all Hira could do was give her husband an ointment for his wounds. Shikharam insisted he was innocent, but he didn’t have a lawyer, and there was no judge to hear his case or grant him bail. No police officer or prosecutor had approved his imprisonment.

Nepal’s park officials were given this free rein decades ago, shortly after WWF first arrived in Chitwan in 1967 to launch a rhinoceros conservation project in a lush lowland forest at the foot of the Himalayas. Six years later, Nepal created Chitwan National Park, 360 square miles of protected land for the area’s one-horned rhinos, Royal Bengal tigers, and slender-snouted gharial crocodiles.

To clear the way, tens of thousands of indigenous people were evicted from their homes and moved to areas outside the park’s boundaries. These people had lived in the area for centuries, building their roofs out of leaves, making medical ointments out of tree bark, and feeding their families with fish from the river.

The park’s creation radically changed their way of life: Now they must scrape together money to buy tin for their roofs, pay hospital bills, and farm new crops. They also live in fear of the park’s wild animals, which, while rising in number thanks to anti-poaching efforts, have destroyed crops and mauled people to death.

Rhinoceros horns can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars on the black market. Professional poachers offer a tiny portion to locals who assist them, which can be hard for impoverished residents of villages to turn down.

Chitwan’s forest rangers work alongside over 1,000 soldiers from the park’s army battalion. Nepalese law gives them special power to investigate wildlife-related crimes, make arrests without a warrant, and retain immunity in cases where an officer has “no alternative” but to shoot the offender, even if the suspect dies. Chitwan’s chief warden serves as a quasi-judge who for years had the ability to dole out 15-year prison terms himself (a recent constitutional amendment transfers all criminal cases that require sentences longer than a year to district courts).

“This was how I learned to pour water into the nose while interrogating. To tell the truth, after that we used this method many times in Chitwan.”

Starting in the 1990s, WWF Nepal set up “anti-poaching units” at the country’s parks. The charity provided monthly salaries for staffers, rewards for informants, and a variety of field gear for rangers, including “khukuris,” curved knives commonly used by the Gurkhas, the famously fierce army brigade, according to internal documents obtained by BuzzFeed News. A former WWF Nepal employee said he was once told to buy North Face jackets for the army officials inside the park — who donned them only after he replaced the North Face logo with WWF’s emblem.

Indigenous groups living near Chitwan have long detailed a host of abuses by these forces. Villagers have reported beatings, torture, sexual assaults, and killings by the park’s guards. They’ve accused park officials of confiscating their firewood and vegetables, and forcing them into unpaid labor.

When forest rangers locked up Shikharam in June 2006, park authorities were scrambling to curb the poaching that spiked alongside social unrest during the country’s Maoist insurgency. They managed to save more rhinos the following year — but the success came at a cost.

Shikharam Chaudhary’s brother, who advocated for his case

Tsering Dolker Gurung for BuzzFeed News

Rangers had not just waterboarded Shikharam, according to eyewitness testimony in police records and a human rights report obtained by BuzzFeed News. Fellow detainees reported that they had seen the guards kicking him in the chest, beating him with bamboo poles, and stomping on him with their boots. Indigenous rights activists who visited Shikharam in jail said they warned Chief Warden Tikaram Adhikari that he was in a bad state.

“We asked the chief warden to stop torturing him and requested that Shikharam be taken to a hospital for treatment, but he just shrugged off our request,” activist Chabilal Neupane told BuzzFeed News. “He told us it was necessary to put pressure on detainees during the investigation process.”

When Shikharam finally fell unconscious, one detainee told police he had heard guards say “the oldie has stopped breathing.” He died at a hospital soon afterward.

After Shikharam’s death, the park released a statement saying he had simply fainted and fallen off a bench after an uneventful week.

Tharu activists demanded a postmortem, obtained by BuzzFeed News, which found “a clear indication of physical violence.” The cause of death was declared to be “excessive pressure applied on the back and left side of the chest,” which rendered Shikharam unable to breathe.

WWF responded to the Shikharam crisis with emphatic support for the park officials charged with murdering him, all of whom, including Adhikari, claimed Shikharam died of natural causes and told BuzzFeed News they weren’t involved in his death.

In a series of meetings hosted by the government’s forest department while the park officials awaited a verdict, staff from a joint initiative between WWF and the government of Nepal asked the Tharu activists to convince Shikharam’s family to drop the criminal complaint, multiple activists told BuzzFeed News.

The section manager of the WWF-backed initiative was then Purna Bahadur Kunwar.

“He would say, ‘Let’s not politicize the issue, it was an accident, who will be there to take care of animals?”’ claimed Birendra Mahato, the chairperson of the Tharu Cultural Museum and Research Center.

Purna Kunwar, now the field coordinator for another WWF project, said he “could not clearly recall the incident in question.” He asked BuzzFeed News to email him further questions, but did not respond in time for publication.

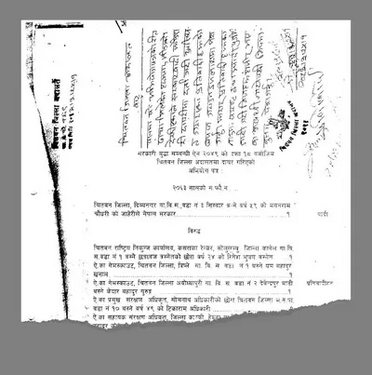

Court documents from the Chaudhary case

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

The family pushed ahead, but to no avail. The Nepalese government intervened and withdrew the case against the accused killers in March 2007.

WWF celebrated. “I have every confidence that this move will renew the motivation of park staff and other conservationists to save Nepal’s rhinos and root out illegal wildlife trade,” WWF Nepal president Anil Manandhar declared in a press release. “WWF will always be there to support this endeavor in any way we can.”

The government’s decision was later questioned in an investigation by a Nepalese human rights group, which reviewed medical records and re-interviewed witnesses. The group concluded Shikharam had died due to torture “at the hand of Park authorities” and called his treatment “inhuman, cruel and degrading.” Assuming that forestry officials could run their own system of justice was “as foolish as to suppose that a child can shoulder the load of a grown up person,” the report said.

The three men who had been accused of murder did not take part in the review, and continued to deny involvement in his death. But another Chitwan official spoke to the group’s investigators about general interrogation practices at the park. “Some types of torture are done to obtain confessions, as the killing of a rhino is a very serious case,” he said. The report was later featured in a book.

After Shikharam died, another indigenous man was found dead at the park’s jail. His family insisted that he had been tortured and accused guards of murdering him. Park officials said he had hanged himself.

A 2008 internal report by a WWF consultant, obtained by BuzzFeed News, came to its own conclusion about Shikharam’s death. The report referred to Shikharam as a “crime convicted individual” — even though he had never been formally charged — and lamented that the arrests of the three Chitwan officials had “widely demoralized park staff and paralyzed anti-poaching operations.”

WWF’s work with violent partners spans the globe. In Central Africa, internal documents show the charity’s close involvement in military-style operations with both a repressive dictatorship and a notoriously fierce army.

In Cameroon, under authoritarian president Paul Biya, rangers have long been accused of beating and torturing people who live near the WWF-supported parks they patrol. The government believes “there are no human rights violations anywhere” in Cameroon, said spokesperson Loh Guillaume Kimbi. He added that taking “concrete steps to prevent poaching cannot and should not be considered at any moment as a gross violations of human rights.”

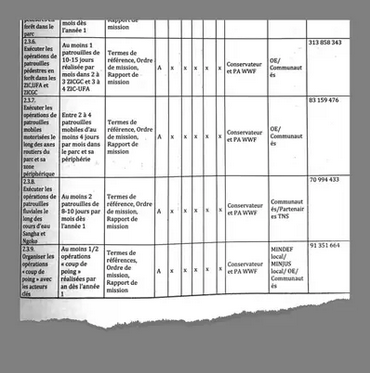

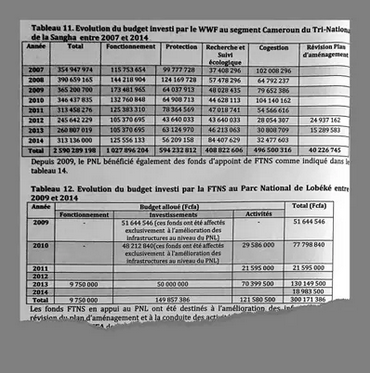

Secret budgeting documents from Lobéké National Park in Cameroon show how closely WWF’s staff have worked with government forces. The charity has helped train them, paid their salaries, and built them homes. It has bought them radios, satellite phones, TVs, 4x4s, and boats. And it has allocated a significant portion of the millions in donor money it spends at Lobéké to “enforcement” activities, including patrols and raids.

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

The park’s management plan says WWF will help organize raids, known as “coup de poings,” on local villages suspected of harboring poachers. A confidential internal report found that such missions, frequently conducted in the dead of night with the help of police units, were often violent.

WWF also worked with the Battalion d’Intervention Rapide (BIR), a Cameroonian special forces unit that has separately been accused of killing unarmed civilians. (Kimbi, the government spokesperson, denied that the BIR has been involved in human rights abuses.) The charity has long denied collaborating with the controversial unit, but emails obtained by BuzzFeed News show its staff in Cameroon responded enthusiastically when an official called on them to arrange a “well-armed” team to catch suspected poachers who they believed had just shot a ranger and suggested they seek the backing of “our colleagues from the BIR.” Three days later, a WWF staff member wrote that he had met with a BIR lieutenant to “solicit their participation” in “this important patrol.”

Internal budgeting documents

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

In neighboring Central African Republic (CAR), a failed state in civil war, WWF’s staff embroiled themselves in something potentially even riskier: an arms deal.

WWF’s local office plays a central role at the Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve on the southwestern tip of the CAR: The charity formally comanages the park and its forest rangers in partnership with the country’s environmental ministry.

In 2009, WWF staff in CAR got involved with the purchase of assault rifles from the country’s army, a force notorious for committing human rights abuses, including decapitating civilians and parading their heads through the streets.

Though the anti-poaching forces it works with are often armed, WWF itself has strict rules against buying or selling weapons. And the park was already in trouble: It was losing donor money in a haze of severe mismanagement. In one internal memo, a local WWF employee warned colleagues of “critical” problems: rules broken, “bad contracts” that paid out “exaggerated amounts,” and other “certain abuses” found in the park’s budget.

One former WWF employee in CAR told BuzzFeed News he was recruited to help “camouflage the deal because none of our funders were permitted to buy weapons.”

But as he examined the invoices, he noticed that the numbers didn’t add up. In an email, he prodded Jean Bernard Yarissem, WWF’s top official in the country, for more detail. An AK assault rifle “should cost us” 266,666 Central African francs (around $615), the employee wrote, “so for 15” weapons “it reaches 4 million.” If so, he wrote, that would leave about 2 million francs unaccounted for: “Does that mean that two boxes of ammunition cost 1 million each?”

Soon it all unraveled. Yarissem explained what happened in a reply to an email sent to nine other officials under the subject line “scandale.” Members of the CAR army had “embezzled” funds meant for arms and ammunition. (The CAR government did not respond to a request for comment.)

Yarissem wrote he was upset the money from the deal had gone missing. Yet he betrayed no misgivings about purchasing the guns, which he referred to as “the weapons that we possess.”

Yarissem did not respond to requests for comment. One official copied on the email initially denied any involvement in the deal to BuzzFeed News, saying, “The idea of WWF buying weapons is unbelievable.” Reminded of details in the email, he backtracked, acknowledging there had been “some discussion” about such a deal, but he did not believe it had gone through.

WWF declined to answer questions about the botched arms deal when asked about it in detail last week.

After that deal went awry, the charity’s staff in CAR did not appear to shy away from involvement with weapons. The charity bought food and fuel for soldiers deployed on an anti-poaching mission during the peak of the country’s civil war, according to two former staffers who spoke to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity. One former WWF staffer said he had personally taught rangers how to safely handle AK-47s and how to conduct defensive combat tactics.

In the years after Shikharam’s death, WWF continued to support Nepal’s forest rangers. In 2008, the charity wrote about the success of their intensive campaign called Operation Unicornis to increase the number of rhinos in Chitwan. The mission included “risky undercover investigations,” according to WWF’s internal newsletter.

The next year, Kamal Jung Kunwar, one of the three officials charged in Shikharam’s death, wrote a memoir about his time at the park. In Four Years for the Rhino, which was published by a Nepalese nonprofit, Kunwar claims to have arrested over 150 poachers, brokers, and smugglers over a three-year period. He insisted he was innocent, claimed he was out of the country when Shikharam was detained, and speculated that the damning autopsy results were fabricated.

But Kunwar freely admitted that the forces he oversaw as coordinator of the park’s anti-poaching operation unit regularly beat suspects. He wrote about giving a suspect a “hard slap,” buying packets of chilli powder for sprinkling into suspects’ eyes, and watching as a fellow ranger punched a boy in the nose until it “started bleeding profusely.” In another, he described a Tibetan boy who refused to speak during interrogation until soldiers poured water into his nose and eyes — the same waterboarding technique Shikharam had described to his wife.

“This was how I learned to pour water into the nose while interrogating,” Kunwar wrote. “To tell the truth, after that we used this method many times in Chitwan. This method was useful in obtaining information.”

In an interview, Kunwar told BuzzFeed News he stood by his memoir: “Everything is in my book,” he said, “just read my book.” He defended his tactics. “It was not torture,” he said. “It was interrogation.”

“I could have hidden the truth and not talked about it in the book,” he added, “but I didn’t because I wanted to present the real scenario. I wanted to let people know about the situation at the time and say, ‘This is what had to be done to save rhinos.’”

In a follow-up email, Kunwar added that it was important to show “respect to others’ human rights,” even if they “are suspected of killing pregnant rhinos, child rapist, human murderer etc.”

WWF spent nearly $3 million on the area including Chitwan National Park in 2009–10, nearly double what it had spent only five years earlier. In 2010, the United Nations released a report documenting six recent extrajudicial killings by army personnel patrolling national parks around Nepal, including Chitwan. Park officials “played an active role in obstructing criminal accountability,” the report said, by falsifying and destroying evidence, falsely claiming the victims were poachers, and pressuring the families of the victims to withdraw criminal complaints.

In one case, soldiers shot and killed two indigenous women and a 12-year-old girl while they were gathering tree bark at Bardiya National Park in 2010. The victims weren’t criminals, another human rights report concluded, just “very poor people who had hardly any source of income.”

Neither report mentioned WWF or made any findings about its relationship with the parks or their officials. The charity has funded anti-poaching enforcement at each of the national parks where the killings took place. One of its major celebrity board members, Leonardo DiCaprio, funds tiger conservation efforts at both Bardiya and Chitwan national parks. (DiCaprio did not respond to a request for comment.)

Two years after the report was released, a Tharu woman was cutting grass near the banks of the Rapti River when a soldier patrolling Chitwan National Park attacked her, she told BuzzFeed News. He stepped on her hands, threw away her sickle, and pushed her into the bushes, where he ripped off her clothes and attempted to rape her. When she resisted, he beat her with a bamboo stick until she lost consciousness.

The soldier was arrested, and a park-affiliated committee tasked with improving local relations stepped in. The woman and her family told BuzzFeed News she was pressured not to press charges against the soldier. “I didn’t get justice,” she said. Her knee is still so damaged that she’s unable to work.

“I am still suffering,” she said.

The sexual assault made national headlines. Despite WWF’s deep involvement with Chitwan National Park and its commitment to protecting indigenous people from abuse, no one from the charity ever met with the woman to discuss the attempted rape, she said. A few months later, WWF gave the soldier’s army battalion an award for combating rhino poaching.

Chitwan park officials continued to lock people up. As of November 2013, there were 80 people detained in Chitwan custody, some whom had been there more than 15 years, according to the Kathmandu Post.

Chitwan National Park did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

During this time, Chitwan’s former chief warden, Tikaram Adhikari, continued working for Nepal’s forest department — and closely with WWF. In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Adhikari denied any involvement with Shikharam’s death and said he was only arrested because of political pressure from Maoists. Shikharam’s autopsy results were fabricated, he said.

After the case was dropped, Adhikari’s influence expanded.

Chitwan’s Rapti River

Frank Bienewald / Getty Images

In 2014, M.K. Yadava, then director of Kaziranga National Park in India — where WWF has backed rangers with supplies and arranged combat and ambush training — produced a document laying out an extraordinarily hardline anti-poaching strategy in which due process would take a backseat.

“Never allow any unauthorized entry (Kill the unwanted)” was a key principle. “If a question arises as to which rights shall get higher priority,” Yadava wrote, “it shall not be the human rights.”

He called on the government to grant him the same sweeping powers to arrest and detain suspects as his Nepalese neighbors. “This is also what we need to do in India,” he wrote.

Yadava personally thanked Adhikari in his proposal. He had invited Adhikari to an international conference where, with a senior WWF representative looking on, Adhikari “shared his positive experiences of controlling poaching in Chitwan by conferring magisterial powers to the Chief Warden,” Yadava wrote.

Yadava’s strategy may have helped curb poaching, but in 2017 the BBC reported rangers at the park had killed dozens of people under his watch, including innocent villagers. “The instruction is whenever you see the poachers or hunters, we should start our guns and hunt them,” one guard told the BBC. “First we warn them — who are you,” another guard said. “But if they resort to firing we have to kill them.” The story led to international outcry, but there was little mention of WWF’s role at the park. “We do not support any procedure that advocates an alleged ‘shoot on sight policy,’” WWF said in a statement, denying that such a policy existed.

But BuzzFeed News can now reveal that WWF India was not only aware of Yadava’s proposal, but supported it. Documents reveal that five WWF employees — including the chief executive of its India office — were listed on his proposal as members of an “expert panel and peer-review group.” One WWF India staffer responded to the paper by offering to help park officials motivate and train its “frontline staff.”

“I could have hidden the truth and not talked about it in the book, but I didn’t because I wanted to present the real scenario. I wanted to let people know about the situation at the time and say, ‘This is what had to be done to save rhinos.’”

Indigenous people have also reported abuse by rangers near other WWF-backed protected areas across India. Just last year, a man who was out collecting wood near Pench Tiger Reserve was found beaten to death. Eight forest rangers were arrested, and police said one of them had confessed that they had burned his body in the forest to destroy evidence.

BuzzFeed News sent a detailed letter seeking comment to numerous Indian Forest Service officials, as well as Yadava. None responded.

Financial documents show that, over the years, WWF has supplied Indian rangers with hundreds of batons and anti-riot helmets, and night vision binoculars for patrols. It also donated uniforms, evidence kits, and a range of vehicles, from jeeps to four-wheelers to trucks and boats.

“In India, if anyone is in uniform they have powers and can abuse anyone at any point,” a former employee of WWF India told BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity.

WWF’s war on poaching extends beyond its support for boots-on-the-ground patrols. Documents obtained by BuzzFeed News reveal the charity has assumed the role of a global spymaster in its efforts to protect wildlife.

Forest rangers often pay people in villages to act as “informants,” documents show. That tactic is risky even when it’s used by trained law enforcement and intelligence agencies, since an informant can be tortured or killed if their cover is blown. Charities shouldn’t get involved with such a “dangerous” enterprise, conservation expert Rosaleen Duffy told BuzzFeed News, because they can lack training in how to collect and transmit sensitive information to keep sources safe.

WWF officials have repeatedly claimed that the charity steers clear of direct involvement in the recruitment and running of informants. “We aren’t law enforcement agencies,” said Drew McVey, a regional officer overseeing operations in Africa, during a recent conference at the London Zoo.

But WWF has been deeply involved in the controversial practice for some time. The charity has helped establish informant networks in authoritarian states, documents show, and it has handed over intelligence to rangers and soldiers accused of human rights abuses.

Internal documents obtained by BuzzFeed News show WWF has offered staffers detailed instructions for finding and cultivating informants, who “help to solve crimes.”

“If a question arises as to which rights shall get higher priority, it shall not be the human rights.”

A global training manual drafted in 2015 declared that people who disclose sensitive information do so with a range of motivations: “Fear; Revenge; Money; Repentance; Altruism.” When they find a potential source, the manual instructs WWF staffers to deploy a three-step approach. Step one: “establish rapport.” Step two: “orientation and guidance.” Step three: “explain safety policies.”

It makes clear that those safety policies only go so far, saying WWF has “a limited means to extract” an informant from a dangerous situation.

In India, Nepal, Cameroon, and CAR, emails and other internal documents show WWF’s active on-the-ground involvement with informant networks. The charity has purchased information and arranged bounties — $170 for a seized assault rifle, for example. For regular informers, it has paid salaries and transportation costs.

One WWF staffer emailed his managers in CAR in 2010 to warn that morale of the secret informants would run low if the charity wasn’t paying them swiftly enough. The staffer proposed a “slush fund” to pay them faster.

The road to Lobéké National Park in Cameroon

Tom Warren / BuzzFeed News

This past rainy season, the muddy red road from the Cameroonian capital of Yaoundé to Lobéké National Park was studded with crater-sized potholes and carcasses of unlucky trucks as it wound through logging towns and jungle villages plastered with reelection posters for President Biya. The three-day drive ends with a welcome sign bearing the name of the Cameroonian Ministry of Forestry and Fauna. WWF’s famed panda logo is stamped alongside it.

WWF executives at its headquarters thousands of miles away in Switzerland claim to keep the Cameroonian government at arm’s length. But this local bureau of “Programme WWF” shares its office with forest rangers employed by the government — meaning WWF administrators work just a few doors down from an ad hoc jail cell where guards have locked up suspected poachers before carting them away to prison.

WWF promises that if it learns of possible abuses by forest rangers, it will “leave no stone unturned” to find out what happened, but its complaint process is not straightforward. In 2016 it established a “complaints resolution process,” overseen by officials in Switzerland, in which WWF pledges to respond to allegations within 10 days. The charity told BuzzFeed News that it informs people of the process through churches and other community organizations.

Yet Baka people throughout Lobéké told BuzzFeed News they were unaware there was anyone they could complain to. Others only learned they could complain because a British NGO called Survival International, which campaigns for indigenous rights, has recently helped dozens of people submit complaints through a separate reporting system for WWF whistleblowers, which is advertised outside the Lobéké bureau on a tattered piece of paper. One complaint submitted online, signed by five people from a village near the park, alleged that forest rangers had tortured an 11-year-old boy.

A sign outside the program office near Lobéké National Park

Tom Warren / BuzzFeed News

“If the guards find you, even with just one antelope, they beat you and make you take your clothes off,” they wrote.

BuzzFeed News traveled to the village and confirmed the account with both the boy and his parents, Moungue and Janine.

The family of three was out harvesting cocoa near the park one day in 2017 when a team of forest rangers and soldiers approached demanding information about weapons used for poaching.

“I said, ‘I don’t have weapons, I’m just working the fields, I don’t know which weapons you’re talking about,’” Moungue told BuzzFeed News. “At that point they said, ‘If that is so, get on your knees, sit down, sleep here.’ That’s when they started to hit me.” They beat the mother, father, and son with machetes, using the blunt ends to hit the soles of their feet.

It was October 2018, three months after the villagers submitted their complaint. No one from WWF had met with them, they said. The original complaint never received a response, according to records obtained by BuzzFeed News.

Last week, WWF issued a press release announcing a “historic” new agreement between the Cameroonian government and the Baka people. It grants them “greater access rights” to the forest, and promises to “tap into” their “traditional knowledge” of the region.

Hira Chaudhary

Tsering Dolker Gurung for BuzzFeed News

Hira Chaudhary said she received a few thousand dollars from Chitwan after her husband’s death. She never heard from the park or from WWF again.

“I am all alone,” Hira told BuzzFeed News.

Near the on-site detention center where Shikharam sobbed into the night, a gold-plated sign from 2016 celebrates the anti-poaching efforts of the “joint conservation operation cell” where park officials and soldiers from Chitwan’s army battalion work together.

Recent changes to Nepalese law mean park officials must now seek approval from a judge to detain someone for longer than 24 hours. But they can still launch cases without involving the police and dictate prison sentences with a maximum of one year. It’s still not an offense for a ranger to shoot a poaching suspect to death in self-defense.

WWF cites Nepal as a shining example of what can happen when the government and people in villages work together. But on the ground, villagers tell a different story.

In December, indigenous people from a village bordering Chitwan gathered behind a mustard seed field and discussed their recent run-ins with park officials. One man told BuzzFeed News that Chitwan soldiers had beaten him so badly the year before that they had broken his eardrum. Others said their fishing permits were abruptly denied for no apparent reason. Even those who have permits said they couldn’t walk near the Rapti River, long the lifeblood of the community, without being hassled by park officials. The president of the nearby community forest — one of the initiatives championed by WWF — said even he wasn’t allowed to enter the forest without permission from the warden.

The villagers said they would be eager to speak with WWF about these issues, and to learn more about how they might look after the land better. “We’d be lucky if they would come to us and talk to us,” said community leader Jaya Mangal Kumal. “They have to consult us, educate us, teach us.”

Yet WWF had never once come to speak with them, the villagers said. They live less than a mile away from the park.

People gather by a mustard seed field to talk to BuzzFeed News

Tsering Dolker Gurung for BuzzFeed News

The three rangers originally charged with causing Shikharam’s death continue to thrive. One, Ritesh Basnet, got a job at WWF Nepal after the charges were dropped. He told BuzzFeed News he “was innocent” and that he “had done nothing wrong.”

Kamal Jung Kunwar’s memoir, in which he admitted to waterboarding suspects, has been adapted for the big screen. A February trailer for the upcoming movie, on which he has a writing credit, portrays rangers slapping poaching suspects before Kunwar is “jailed by the corrupted system” as part of a “conspiracy.”

In 2014, WWF gave a Leaders for a Living Planet award to Chitwan National Park. The charity handed the award to Kunwar, who by then had become the chief warden.

A photograph shows him smiling with the charity’s top officials, including then-president Yolanda Kakabadse and then–director general Jim Leape.

Kakabadse did not respond to a request for comment. Leape told BuzzFeed News in a statement he “was not aware of concerns” about Kunwar. “As I expect they have told you, given the seriousness of the allegations WWF has decided to launch an independent review to determine exactly what happened,” Leape said.

In an interview for WWF’s website, Kunwar had warm words for the charity. The support WWF provides “is really helping us to do our job well,” he said. “I thank them for this.”

BuzzFeed News reported from Nepal in partnership with the Kathmandu Post, which has today published its own investigation into WWF’s work in the country. Read the Post’s story here.

Tsering Dolker Gurung, François Essomba, Cecile Dehesdin, Alice Kantor, Morgane Mounier, and Emma Loop contributed reporting to this story.

This is Part 1 of a BuzzFeed News investigation.

To read the other articles in this series, click here.

Trigger Warning

Trigger warning: suicide, self-harm, eating disorders

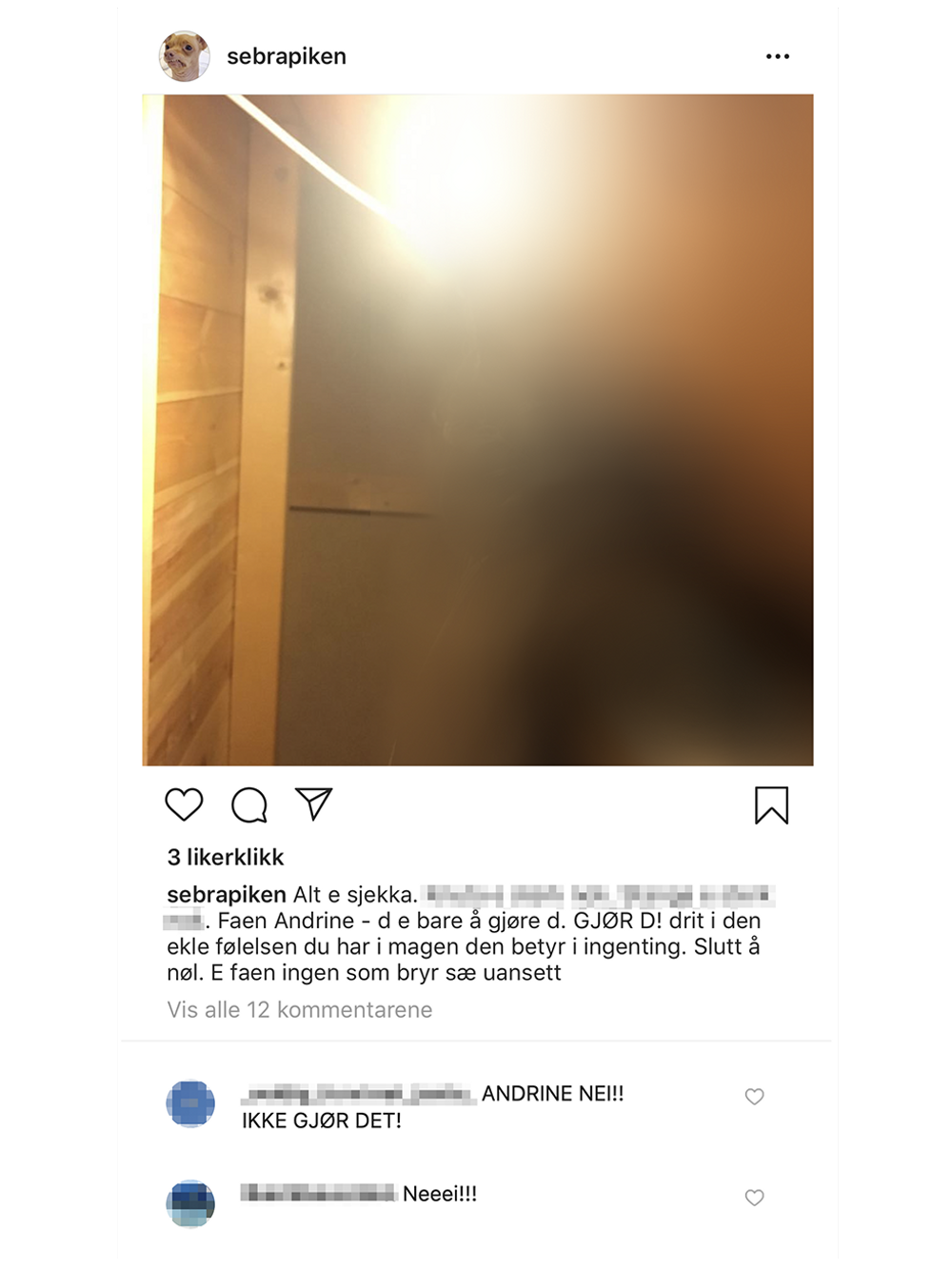

The cubbyhole in which Andrine (17) has hidden herself is so small she must sit on her knees. From her mobile she posts several entries on her secret Instagram account. Hundreds of Norwegian girls on this hidden network can read her messages about her wish to die.

NRK has investigated the dark network on Instagram. Andrine is just one of the girls connected to it. At least fifteen Norwegian girls in this closed group have, within a few years, taken their own life. For a long period, Andrine has been one of the most active users on this site – even into her last hours.

Between her bouts of crying she is hardly aware of the two adults standing outside her cubbyhole. She’d rather concentrate on the network and on getting the courage to send what will be a directly transmitted suicide note she writes in one of her last messages on Instagram:

All is checked. Shit Andrine – it is only to do it. DO IT! Don’t give a shit about the disgusting feeling you have in your stomach that does not mean a thing. Stop hesitating. Hell, nobody cares anyway

Comment: ANDRINE NO!! DON’T DO IT!

Comment: Noooo!!!!

(All censorship of the Instagram-postings has, in this story, been made by NRK)

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

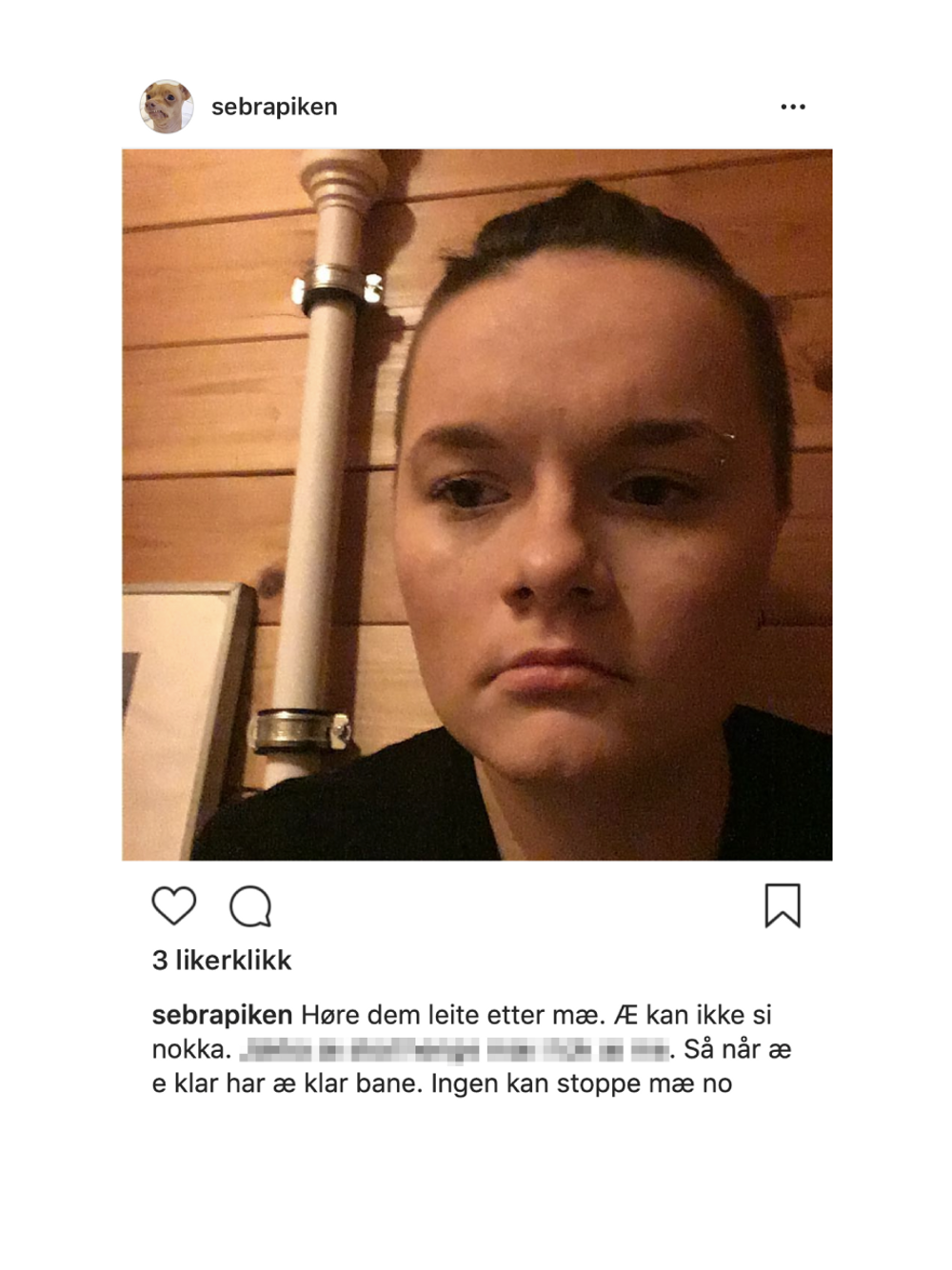

“At last everything is ready,” she writes. For nearly ten months she’s been living in a private child protection institution. On this day the last brick falls into place.

I hear how they look for me. I can’t say anything. (Censured, censured, censured, censured, censured). So when I am ready, I have a clear path. Nobody can stop me now.

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

She also sends several text messages to the staff on duty this late evening in March 2017. Just before 10.30 pm Andrine sends a message where she says goodbye to her mother.

“Tell her that I am sorry for ruining her life. Just tell her that she was the best mother I could ever have had.”

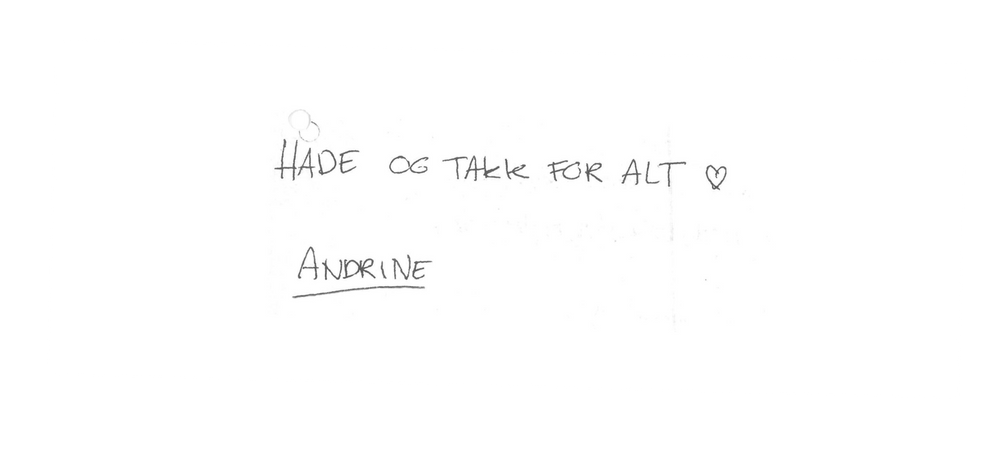

In her room there is also a handwritten note. “Bye and thanks for everything,” she writes, ending with a heart.

“Bye and thanks for everything”

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

The staff finds out where Andrine is hiding and tries to get her to talk. Finally she agrees to unlock the door.

Everything now looks as if it will sort itself out, but on the way down from the second floor, the staff suddenly hears a sharp thump from the room where Andrine is.

Then everything is quiet.

The staff runs upstairs again, but gets no response. The emergency centre is being contacted, while the staff tries to break in with a crowbar.

Just a few minutes later an ambulance is on site, and the girl is being brought out.

But for Andrine it is too late.

After four days in a respirator in hospital, she dies.

Photo: Patric da Silva Sæther

In the cardboard box

The cardboard box with Andrine’s things has been standing in the hallway for nearly two years. Her mother Heidi got it from the police just a few weeks after her daughter’s suicide.

Photo: Patric da Silva Sæther

After that, it has remained there, untouched but never forgotten. Almost every day she looks at it, but is too afraid to open it.

That’s because the mobile from that evening when Andrine died, is in the box.

Heidi is afraid there are things on it she actually does not have the strength to see.

Photo: Patric da Silva Sæther

After nearly two years she at last picks up the courage.

On the mobile there are two Instagram accounts: the normal one she followed herself, but also a completely unknown profile, “Sebrapiken.”

Photo: Patric da Silva Sæther

She logs in and feels how nausea is building up.

There she finds a dark and frightening world, full of girls like Andrine.

The hidden network

Trigger warning: suicide, self-harm, eating disorders

On a hidden network with private and often anonymous profiles, hundreds of girls suffering from mental illness are meeting. In this secret place they give each other comfort and support, but they also share their darkest thoughts.

But even worse: they are posting pictures and films of serious eating disorders, deep wounds after self-harm, suicide thoughts, attempts and methods.

They often mark the accounts with “TW” or “Trigger Warning” to warn followers of content that may affect them in a bad way.

From Andrine’s mobile, NRK gets access to this secret room. Before she took her own life, she was one of the most active users in this enclosed environment. From her hidden Instagram account we find over 1,000 users posting depressive content of self-harm and suicide. Nearly 500 of the profiles are Norwegians. A mapping of this environment reveals that in just a few years, at least fifteen young girls have taken their own life.

– Immediately after the Easter break this year, a 22-year-old in Førde takes her life. Konstanse is also part of this world with several suicide attempts behind her. Before she dies, she deletes all her profiles on social media.

– Just a few days before, another suicide takes place. Cecilie can fill a whole room with her heart, but only fills a small corner of the sofa, her friends say about her. She is morbidly emaciated and is self-harming. The 20-year-old tries to take her own life several times and goes in and out of psychiatric treatment. On the eve of Easter 2019, she kills herself in Larvik.

– Leila Mariell from Vadsø has, for a long time, struggled with psychiatric problems and self-harm. She has been admitted on a number of occasions and has tried to kill herself several times. On Instagram and Twitter she has a lot of contact with others who also have difficulties. She finds a lot of support in this environment, but can also see that they can make each other more ill. By her followers she is seen as one who helps and support others, but she could not help herself. The 24-year-old dies in February 2019.

– In Østfold, a 17-year-old girl is together with another girl from the Instagram-group when she takes her own life in May 2018.

– Tine has several hidden profiles and is open about the environment she’s part of. She thinks it is about supporting and helping each other and can perhaps not see how damaging it can be for her and others. The 34-year- old struggles heavily with mental disorder, has an eating disorder and is self-harming. Tine takes her own life in October 2017.

– Merete’s great hobby is to sew and knit. She is training to be a child carer, but suffers mentally and has been in and out of institutions for many years. Finally this Haugesund girl plans her own funeral. In a final letter to her family she writes what is to be inscribed on her grave stone: Faith, hope and love. Merete dies in September 2017 at the age of twenty-nine.

– “Dear Mum, I’m writing to say goodbye. Love you so much. We will meet again.” This farewell letter lies in a flat belonging to a 19-year-old girl in Bergen. She has just moved into her own flat, but suffers mentally and injures herself. Her wish to die has been there a long time. She takes her own life in November 2016.

– In Rogaland, a 16-year-old girl is admitted for psychiatric treatment. She suffers from eating disorders and serious self-harm. She takes her own life in August 2016.

– Anette is only fifteen. The girl from Brønnøysund has just gotten a summer job and wants to buy a motorbike with the money. In a few weeks she is about to start an electronics course at college. She kills herself in July 2016.

– In March 2016 Karoline from Bergen dies. The 20-year-old shared many difficult thoughts and wishes to take her life in the network on Instagram.

– In February 2016 another girl from Bergen takes her own life. Camilla was only eighteen years old. “Rest in peace, little friend,” the family writes in the obituary.

– In the same month Marthe, who was also a part of the network, dies. She was bullied, injured herself and tried to take her own life several times. Marthe was only sixteen.

– “Karianne got peace at last,” says an obituary from 2014. She was depressed and did self-harm, but did not share her darkest thoughts with her near ones or in treatment. Within the network she had close friends, but was only fifteen years old when she died. Karianne took her own life in Stavanger after having given the followers a warning on Instagram about her plans.

– Eline dies in Bærum summer 2012, twenty-two years old. Before her suicide she struggled for a long time with self-harm and depression. She was active on several blogs before she took her own life.

They’re from all over the country and did not usually know each other outside the network.

They suffered from eating disorders or self-harm.

Half of them were below the age of twenty when they died.

Within the network, NRK has seen concrete examples on how methods for self-harm or attempts of suicide have spread from one member of the group to another. The worse an entry from a girl is, the more attention and care they receive from others.

Andrine

At only five years old, Andrine is bouncing around in her sister’s gym-suit and two years later she turns up, proud and a bit nervous, to her first training session. Throughout her childhood and youth at school, gymnastics is something she really loves, also as an instructor to the younger children.

Andrine grows up just outside the centre of Tromsø together with her mother and nine year older sister. “She had a normal childhood with much care and love,” says the mother.

At school she fulfils her duties and does well in most subjects. She has a winning way and lots of friends. She is a ray of sunshine with so much humour and high spirits that she is missed whenever she is away for just one day.

– “Andrine was very easy to like. We joked a lot together, even after she became ill. We could say one word wrong, look at each other and then burst out laughing,” says Heidi.

Andrine paints and draws and likes to potter around the house and her room. She has her own style, a bit playful and a bit boyish. When she puts on make-up, it is always soft and discreet. Andrine knows what she is doing.

Outward she appears tough and comfortable, but without anybody knowing it, she has serious psychological problems.

In February 2017, Andrine posts an old picture of herself. It is from a holiday with palm trees and flowers in the background. Andrine is smiling to the camera, dressed in a singlet and shorts.

TB to when I wasn’t sick, but just one who felt life had a few downs but I had been self-harming for nearly a year. The cuts were not particularly deep but I was also «clever» at cutting myself in places that wasn’t showing. Very few knew how I was struggling and that was fine. I was waiting fora n appointment at Bup (Child and Youth Psychiatric Clinic/transl.), but otherwise I was fairly OK.

Soon, she begins to cover herself up, as her arms, under her clothes, were covered with scars and wounds.

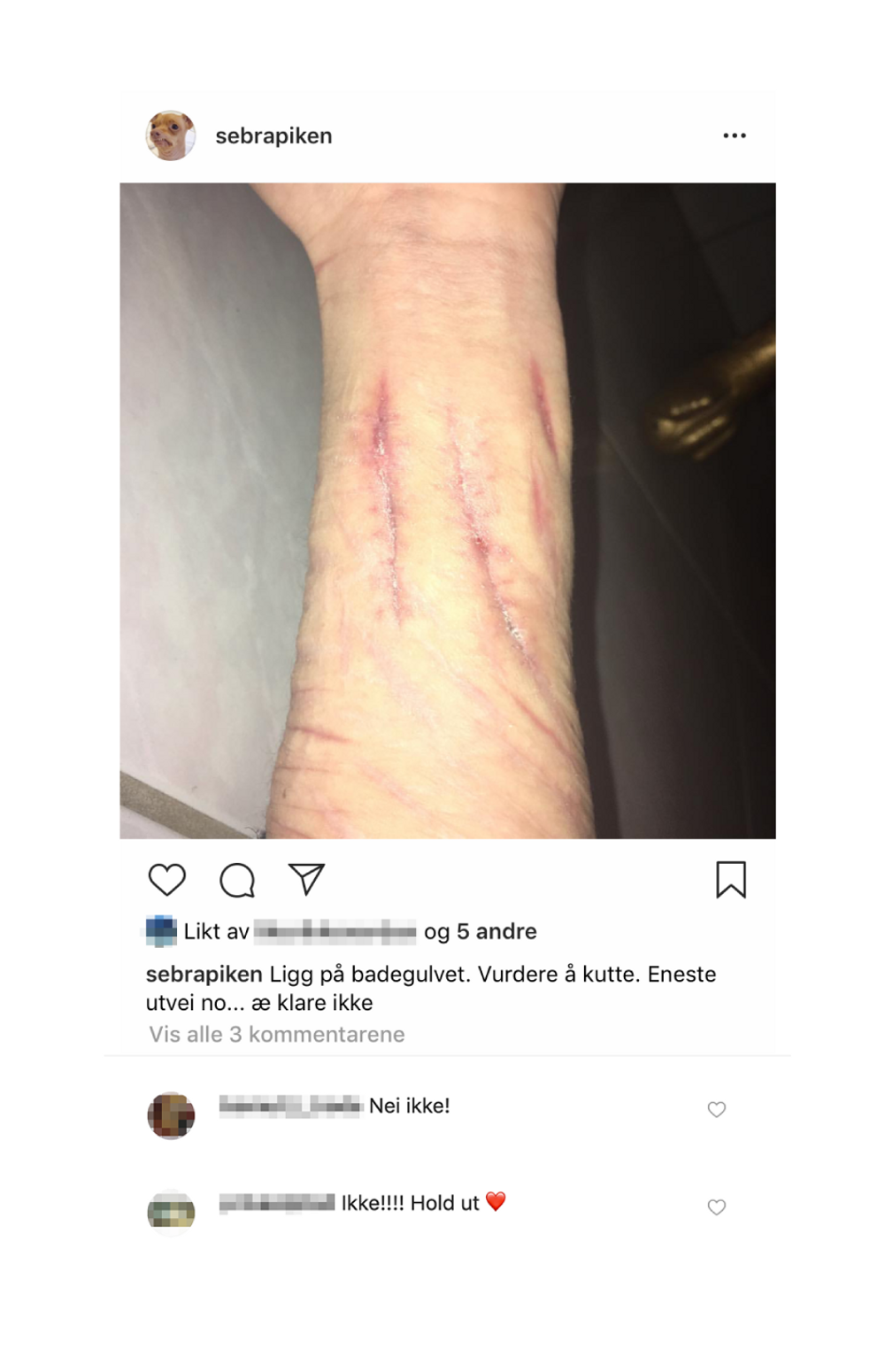

Trigger warning: Self-harm

The first cuts

Andrine’s first meeting with self-harm was at school. She’s together with a friend when some older girls show their scars. She had never seen anything like it before and in her diary Andrine writes that this is “extremely stupid!”

At the same time there is something from this happening that sticks.

At fourteen, Andrine starts to cut herself. It happens after what she herself describes as a “heavy summer holiday.” Hidden from everybody, this self-harming takes place more and more often, while the cuts get deeper and more serious.

She herself describes self-harm as an “adrenalin kick.” A form of mastering that lets her handle evil and destructive thoughts: “It feels like being locked into a room where self-harm is the only emergency exit,” Andrine explains to a psychologist.

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

Trigger warning: suicide

The first suicide attempt

In August 2015, Andrine is admitted to hospital after a suicide attempt. The risk of suicide is not overwhelming, according to the doctors, but at the same time they warn of the danger of a repeat and the fact that the girl can “take her own life as an accident.”

After the suicide attempt, Andrine explains that she’s suffered of anxiety for many years. She never feels good enough and is convinced that nobody likes her. She also has great problems with controlling her feelings, especially when life goes against her.

Things that most people see as trivial can release endless sadness and crises. Self-harm and suicidal thoughts “can be seen in this context,” the report from the hospital says.

There is also another reason why she hurts herself. Andrine reveals this several months later.

The dangerous voice

Andrine is hearing a voice in her head. It suddenly appears and orders her to take her own life.

Together with “The Voice” there is also a small girl. Andrine calls her “Dagny.” A drawing in her diary shows a character that looks like she’s been taken from a horror movie. The eyes are pierced out and the mouth sewn together with thick stiches. “The Voice” has done this, and if Andrine doesn’t do as “The Voice” commands, the same thing will happen to her.

In order to ignore “The Voice,” Andrine has to suffer pain, she explains, either by cutting herself or swallowing dangerous objects.

Andrine is now being treated at the hospital, first in conversation therapy and later by medication. After a while she is seen as being well enough to be discharged, but Andrine does not want to go home.

The relationship with the family is very difficult, she feels. Andrine is now so sick that she requires more frequent follow ups than her mother can give her. Contact with her father was broken when she was ten years old, and Andrine feels she’s only a burden that nobody cares about.

She’s kept in hospital. And while her contact with the real world is shrinking, her life on Instagram takes increasingly more time and space.

The hidden account

She calls herself “Sebrapiken.” Probably from a book with the same name about a girl who also injures herself.

Lying on the bathroom floor, thinking of cutting. The only way out now….I can’t do it

Comment: No don’t!

Comment: Don’t!!!! Hold on (heart)

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

Just like Andrine, many of the girls on the hidden network seem to be completely normal girls from all over the country. Often very young, some as young as fourteen years old. They often don’t know each other in real life, only online.

The girls use their own “tribe language” with codes for diagnoses, what type of self-harm they’re into, how many times they have been admitted to a hospital or tried to take their own life.

In this, Andrine at last finds a place where she doesn’t feel alone. Here she gets support and understanding from others who suffer the same and who understand her situation.

But most of all, she has found a fellowship where sick girls are exchanging negative thoughts and experiences. In a world without adults, they share tips and advice on self-harm and suicide.

Andrine quickly becomes a person that most people know of in this secret environment.

Being transferred to child care

During the next months, Andrine is more or less continuously admitted to several different institutions.

In several places it seems like things are going well, at least in the beginning. The girl seems positive and happy, she follows her treatment and often shows signs of improvement.

Then come the downturns, abruptly and worse. Self-harming gets more frequent and takes new forms. Andrine starts to swallow harmful objects and the cuts find new spots on her body.

In February 2016, Andrine’s condition has deteriorated so seriously that she’s transferred to child protection, and in May she moves into a private institution called “Jentespranget.”

Here she remains during the last months of her young life.

A new beginning

Jentespranget is situated at Stord, between Haugesund and Bergen. It is a department for seriously-ill girls. Some of whom are often under around- the-clock supervision.

Andrine gets her own room with two staff members looking after just her.

She’s given a new treatment plan and sees a psychologist regularly. Gradually, she begins to think of her future and attends school when she is capable. To keep her thoughts away from evil, the days are filled with activities. Andrine is to be taught to take responsibility for her own life and has to wash her clothes and keep the house in order.

She starts working out, and as a part of her treatment Andrine begins horse therapy.

But during the summer she suddenly falls into extended, heavy depressive periods. Her thoughts on self-harm and suicide increase, especially in the evenings, according to staff.

Andrine has access to both her phone and the internet, also at night. In two months she posts over 1,500 entries. She posts private messages several times a day and much of those are images of self-harm and thoughts on taking her own life.

At Jentespranget they notice that she’s very active on the Internet. In a risk assessment the employees write:

“Andrine has on several occasions informed that she wishes to take her own life. She has also written suicidal thoughts on social media, on a closed Instagram profile.”

During her stay Andrine attends several meetings on how damaging this environment can be for her, but she takes no notice.

I and people in charge talk about “self-harming Instagram” (smiling face upside down)

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

The staff has no right to take the mobile away from her, but when they suggest banning it for a period, Andrine uses self-harm as blackmail to keep it.

As Andrine is voluntarily admitted to the institution, the staff has only limited authority to use force against her.

You snitch, you die

As Sebrapiken, Andrine is “safe.” Many users also mark their profiles like this. In this group “safe” means to follow an unwritten rule that nothing from within the network is to be shown or told to outsiders. There’s a rule of silence, and it’s simple: “You snitch, you die!” If you don’t keep quiet, you can be blocked or closed down by others. Some say this rule is valid even when there’s a question of life-or-death for the girls.

But Andrine does not want to follow this rule when somebody is trying to take their own life. Once she called an institution in northern Norway to tell their staff that one of the girls living there was about to commit suicide.

Contagious behaviour

In August 2016, Andrine experiences online that a close friend from within the Instagram network kills herself. She takes this very hard and is clearly affected by her death. The two following months she is admitted six times after overdoses and other suicide attempts. During this period she has to get nearly 200 stitches.

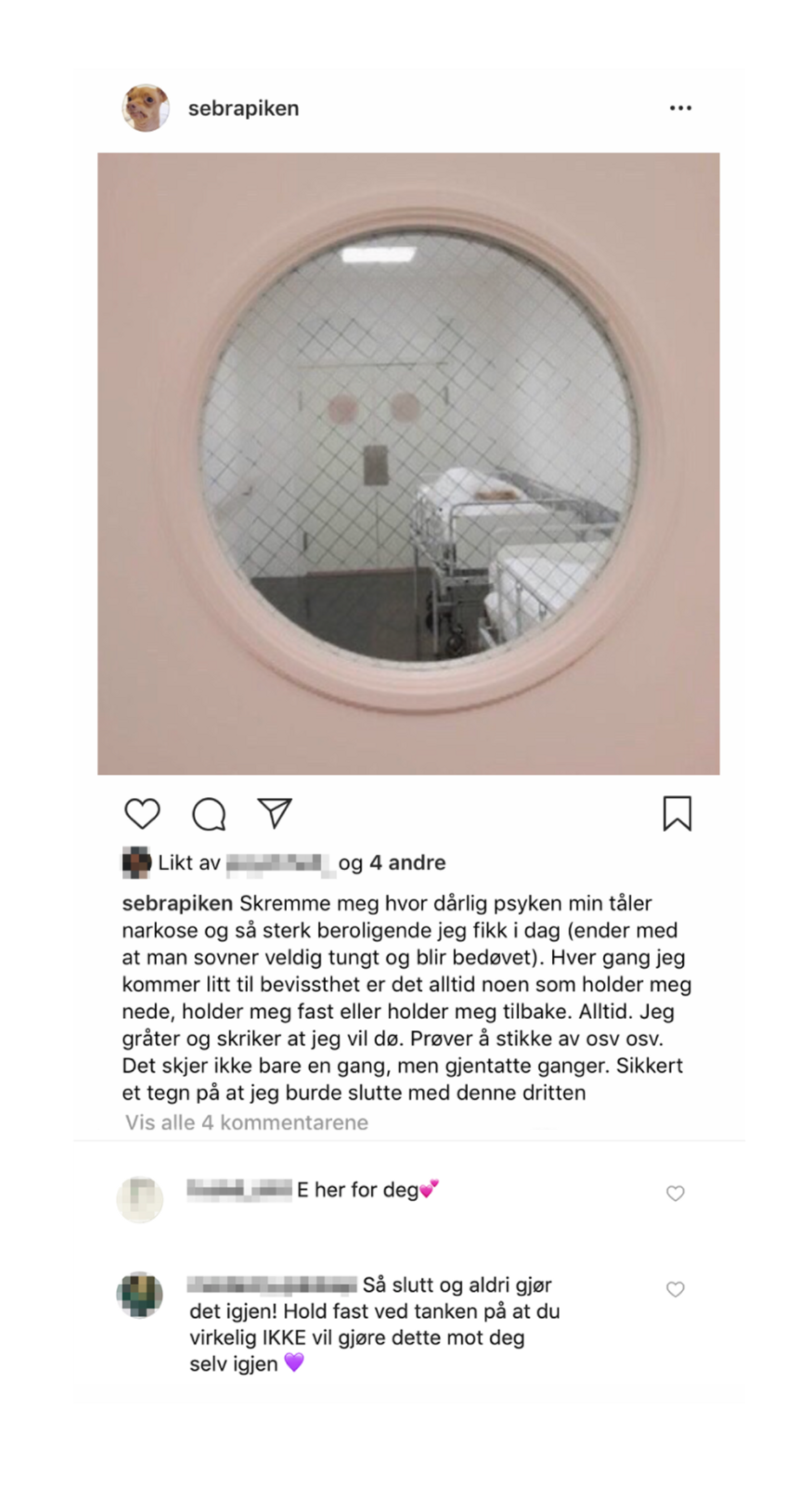

And so, she is sent to hospital in Bergen. She has suffered severe internal injuries after swallowing dangerous objects and must be operated upon. After surgery, a new suicide attempt happens at the hospital, and Andrine is only a whisker from death.

It frightens me how bad my psyche takes anaesthetics and how peaceful I became today (ended with me sleeping very heavily or being anaesthetised). Every time I become conscious there is always someone holding me down, keeps me tied or holds me back. Always. I cry and shout I want to die. Try to run away etc. It does not happen once, but repeatedly. Perhaps a sure sign I should end this shit.

Comment: I am here for you (hearts)

Comment: So stop it, and never do it again! Hang on to the thought that you really DO NOT want to do this to yourself again (small heart).

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

Now Jentespranget asks for help. To the child protection agency in Tromsø they write: “We must, to the best of our ability, keep this girl alive,” but this is difficult with the framework they now have. For a period they employ extra staff to cover Andrine.

The fear of turning eighteen

Andrine is now only weeks from turning eighteen. After years as a hot potato in the system, in and out of psychiatric institutions, in and out of meetings on who shall take care of her, this is something she fears more than anything: having to take care of herself.

Already two years before Andrine dies, a previous entry in a hospital report says that she is especially vulnerable to major changes.

She needs security and stability, and we see that her self-harm increases as soon as discharge is being approached. She says she does not see many possibilities in the future, her thoughts regularly return to taking her own life.

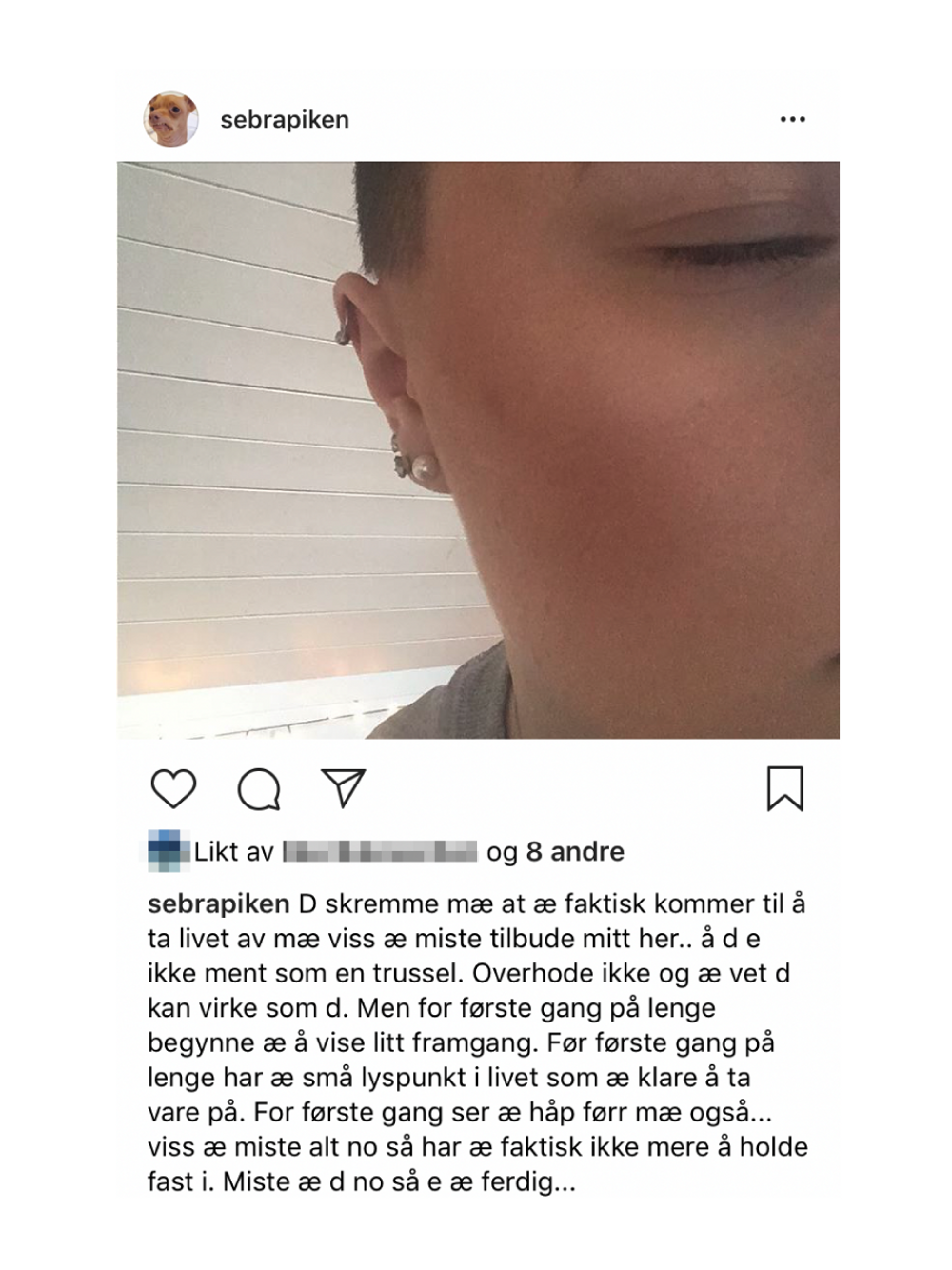

At the beginning of 2017, Andrine is, despite her situation, given the decision that she is not guaranteed a place at the institution Jentespranget when she turns eighteen. This really frightens Andrine, now that she finally has arrived at a place that she really likes.

It frightens me that I actually will kill myself if I miss the offer of a place here. This is not meant as a threat, although I know it can sound like that. But for the first time in ages I begin to show some progress. For the first time I have small rays of light in my life that I love. For the first time I see a bit of hope for myself as well…..if I lose everything now I really have nothing more to hold on to. If I miss it now I am finished…

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

Andrine desperately wants a quick decision. She and her mother are attending several meetings with the child protection agency without reaching a final decision. During so-called cooperative meetings about Andrine, nobody can give the girl a clear answer.

The last day

In the morning on the day Andrine dies, the staff perceives her as being very “heavy.” Already before breakfast there’s a text from Andrine saying she’s not feeling good. She feels completely “rock bottom.”

The staff is united in keeping a certain distance. Experience shows that the closer they are to her in these situations, the greater the risk of her hurting herself.

Andrine starts the day in the stables, and after having fed the horses she seems better. At dinner she jokes and plays around with the employees, and in the evening they all go to the cinema.

In the middle of the film the staff gets a call from one of the other girls in the house. She says that Andrine has plans to take her own life later that evening and that she has posted this on Instagram.

Since Andrine seems stable and at ease, their joint decision is to bring it up when they get back home.

On the way from the cinema Andrine posts this image.

Sitting in the car smiling because the film has ended and so has my life.

Comment: No, Andrine!!! (sad face)

Warning: these images contain graphic content that some viewers may find disturbing

Back at the house Andrine runs upstairs to her room before anybody gets to talk to her. They can hear her cries and suggests a trip to the doctor, but Andrine refuses. She doesn’t want anybody to stop what she has planned.

A while later a text message arrives in which Andrine says thank you for everything. The search for her starts, but on the same evening Andrine’s life is over.

Photo: Patric da Silva Sæther

“Poor child of mine! Just to think how hurt she must have been and I did not manage to help!” says Andrine’s mother Heidi and puts her daughter’s mobile phone away.

Photo: Patric da Silva Sæther

She wants Andrine’s story to be included and help to reveal this hidden network because it is a dangerous arena, she says.

– “This is completely without any filtration. Had Andrine not had this relationship with the Internet, I don’t believe it would have ended as catastrophically as it did.”

Just a few weeks after Andrine’s death, the child care agency formally cancels her place at Jentespranget. Ending date for her stay: the day Andrine would have turned eighteen.

An official report following Andrine’s suicide, states that the employees at Jentespranget did everything they could in the situation and that the follow-up of this girl was defendable.

Epilogue

The day after Andrine’s eighteenth birthday, Heidi finds an envelope in the letter box at home. It is a thank you letter from the director at Oslo University Hospital.

In the letter it says that Andrine’s organs, after she’d been disconnected from the respirator, have given new life.

– “When I came to the part about the children, I just burst into floods of tears. I had really hoped that she would save some children, so it was good to hear,” says Heidi and reads the last lines in the letter aloud:

Four adults and two children have been given a new life. I hope this can be a comfort for you and Andrine’s sister to think about. I wish you as good a future as possible and feel with you in your sorrow.

This story is based on Andrine’s profile and own notes, journals from the child and youth psychiatrists involved, the child care agency and other public documents connected to her treatment, plus interviews with Andrine’s mother and conversations with those closely involved with the fourteen other girls who have died. Their families have accepted the use of pictures and names of these girls.

Neither Jentespranget nor the child and youth psychiatrist treating Andrine are willing to be interviewed in regards to this matter.

The Children, Youth and Family Agency in Region North and its Area Director Mr Pål Christian Bergstrøm, writes to NRK:

“This is an extremely serious case. For us it is the worst thing that can happen – a child dies when under care of child protection. We feel empathy for the mother and other survivors. The employees working with Andrine are also experiencing great sorrow. It is very difficult to be informed that Andrine felt we did not do enough to help her. This case was, however, extremely involved and complex.

Legislation set for the purpose of securing children’s rights can in situations where the children are as ill as Andrine, limit the child care agencies’ ability to provide the assistance that children need. This case also highlights the demand aid organisations face when this form of social media is used.”

Trigger Warning

- Trigger Warning – TW – is a term used within some closed groups on Instagram. It is used to warn against strong pictures, or content, that can release evil thoughts and dangerous actions. Users insert this ex- pression in their biographies to warn others from entering their profiles

- For over a year, NRK has followed a network on Instagram where this expression is frequently used. Young girls, mostly teenagers, discuss suicide and self-harm and share images showing how they have injured themselves.

- In this period NRK had identified fifteen girls from the network who have taken their own lives. In one case this took place almost as a live stream on Instagram.

- This network is not well-known among professional health carers in Norway. There is also very little research performed in this area.

- In a series of articles NRK highlights this dark and hidden network.