Defined by silence

Despite the fact that these days, so much is being said, shown, and written about Ukraine and the war that Russia waged on her; despite all the news, numerous interviews and videos of President Zelensky speaking to whoever is willing to listen; despite constant buzz in the Ukrainian segments of social media where people coordinate humanitarian help, support to the territorial defense units, the relocation of people, and million other urgent matters; despite all these the inner condition, the state of being of the country is probably best defined by the word ‘silence.’

Silence can stem from different circumstances and possess various qualities. It can be voluntary or forced, deafening or revealing, powerful or paralyzing. What unites all these is absence as an antonym to presence; the absence of something that could have been but is not. This silence in Ukraine in the middle of murderous noise is the absence of the words, expressions, thoughts, actions, intentions that could have been said, stated, done, shown, uttered if there was no war.

Silence also does not necessarily mean the absence of people, quite the contrary – the more people whose voices have been silenced, the more deafening and horrible it grows. This is especially true when talking about culture: Ukrainian culture today is a void compiled of empty spaces that could have been filled with books, exhibitions, performances that did not happen – and most probably, will not happen for a long time.

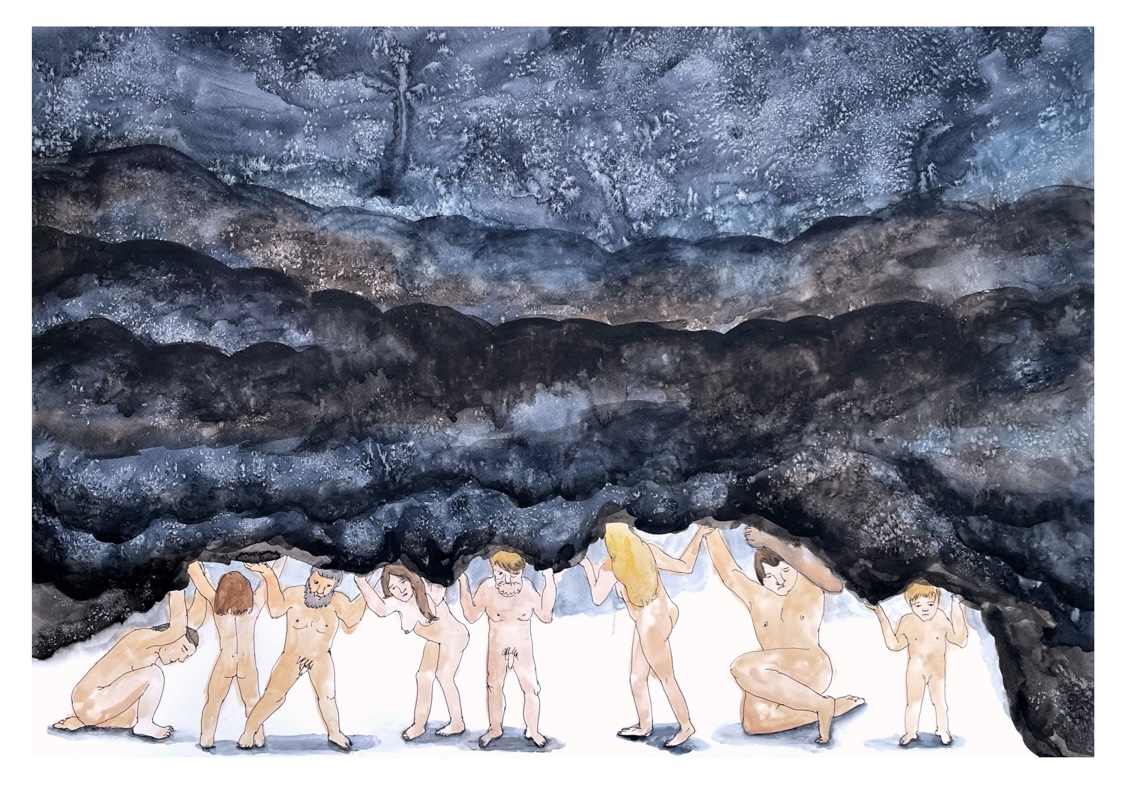

Kinder Album: Ukrainian Titans Holding Up the Sky. 2022, published on Instagram. Image courtesy of the artist Kinder Album.

Back in 2014, at the de facto onset of the current invasion – occupation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine, – the outstanding Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko switched from her writing to producing endless interviews and articles, predominantly for western media. She called it ‘getting into a tank’ – an expression which later became a title for her collection of essays and interviews.

Yet again, everything was brought to a halt on 24 February this year, but on much larger and more terrifying scale.

This time another outstanding Ukrainian writer, Sofia Andruchovych wrote: ‘Before the war, I was a writer. Today, on the ninth day, I feel unable to string two words together’.

Film director Marina Stepanska stated on her Facebook in A Letter from Ukraine: ‘I used to be a filmmaker, now I’m not.’

Meanwhile, artist Lesya Khomenko left everything in her studio in Kyiv and took to Ivano-Frankivsk in Western Ukraine with her daughter, and started a lab for displaced artists. She calls it ‘a therapeutic space’ to look at the current situation and try to deal with it through collaborative work. She says, ‘We left all our works behind, we are left with nothing, without a biography. When some might have their works digitalized, others like myself have only material pieces.’

So, what are the voices of the silence? What happens to art (and artists) during the war? The question is twofold. One problem is what happens instead of art that did not happen. The other: what happens to art that already happened.

The art that already happened

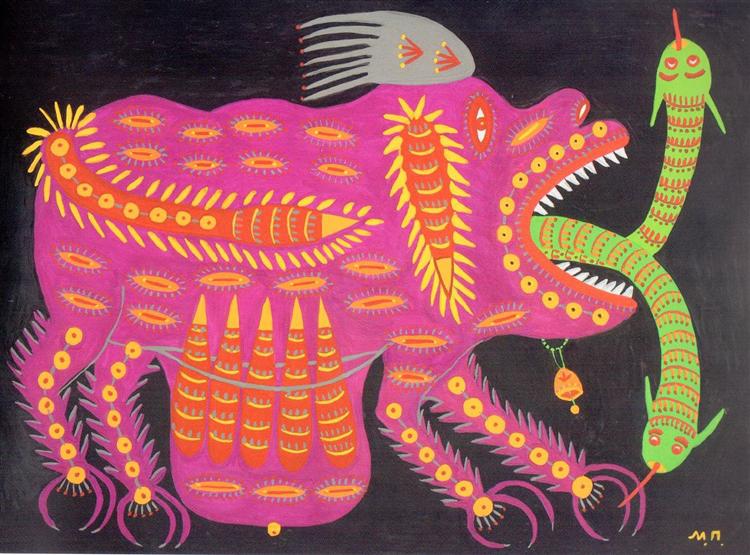

A few days after the war started, globalmedia picked up the story of Maria Prymachenko’s works being destroyed as a local history museum burned down after missile hit in Ivankiv, near Kyiv. The story went viral spreading from arts magazines and newspapers to mainstream media: colorful phantasmagoric images of Prymachenko’s imagined flora and fauna covering printed pages and newsletters.

Shortly after, thenews surfaced that some of the paintings may have been saved by locals – maybe even more than those destroyed. It is worth noting that the main collection of her works was stored elsewhere in the first place. Yet, this information never made it to the top headlines, and neither did the news about the destroyed or severely damaged museums in Kharkiv, Mariupol, or Chernihiv.

A powerful visionary painting by Maria Primachenko: May That Nuclear War Be Cursed! 1978. Fair Use via Wikiart.

Was this information simply swallowed by the tsunami of other news? Lost among the daily reports of children being killed, civilians kept hostage, whole cities destroyed? Maybe people simply more important than artworks, allowing the threat to lives overshadowing the problem of cultural heritage? It may have been affected by the authorities’ reinforced demand not to publish any visuals and not to disclose the locations of the missile hits and destruction?

Or was this silence already internalized and accepted? Did museum workers and cultural professionals remain silent because they understood that any information about the collections, their whereabouts, their conditions or further prospects equaled putting a target on them?

On the other hand, the uproar about the destruction of Prymachenko’s works might have concentrated on something other than the artist, or even the works. It might have been another omission created by the war, a tangible example of loss when destruction was the only story to tell.

In war, the materiality of destruction prevails over the materiality of existence. The physical pressure and the finite mass of the rubble left after the missile hits a building feels like the end of the sentence. All said. Period. Nothing can be done. Time to move on.

But those who survive, be they people or objects, need their stories and histories. Without them, Prymachenko stays a ‘folk’ artist whose works appeared on postal stamps, was awarded an art prize (notably, both these happened still under the Soviet Union), and was praised by Picasso. These little scraps of info were mentioned all over international media.

In this context, her unique story as an autodidact who never left her village, her cosmovisions of interconnectedness of life that blurred the borders between the reality and dreams, the role of her works for the generations of Ukrainian artists and in forging Ukrainian cultural identity have no place and no attention. In the place where a story should be told, there is silence.

Even more silence occupied places of stories that could have been told. Museum collections are stored in basements in undisclosed locations,: and museum directors refuse to talk about the specifics; activists raise funds and collect basic necessities to support the people who save the artworks. Grassroots initiatives like the Museum Crisis Center provide packaging material and fire extinguishers, prioritizing museums in small towns and villages. These objects of varying value, origin, and provenance,are parts of a cultural heritage that would need to be exhibited, contextualized and analyzed, woven into the complex history of a country whose people were deprived of history for a long time. But right now, security prevails over the need of storytelling.

And then there are the artworks of living artists too, left in studios and galleries basements, sometimes rescued by volunteers or fellow artists, sometimes already lost forever.

The art that did not happen

If some of these works are never to be recovered, what does it make them? Will they be merely a ‘lost biography’, in Lesya Khomenko’s words? Are they an already lost heritage? And what’s the difference? When and if the images, the digital copies of these works are to be exhibited sometime in the future, how will the present, material objects created by the same artists during the war look next to them? Perhaps, there will be a note, a small caption next to each of them saying something like ‘This work was not the one planned by the artist or created out of her/his good will. It was created by the war.’

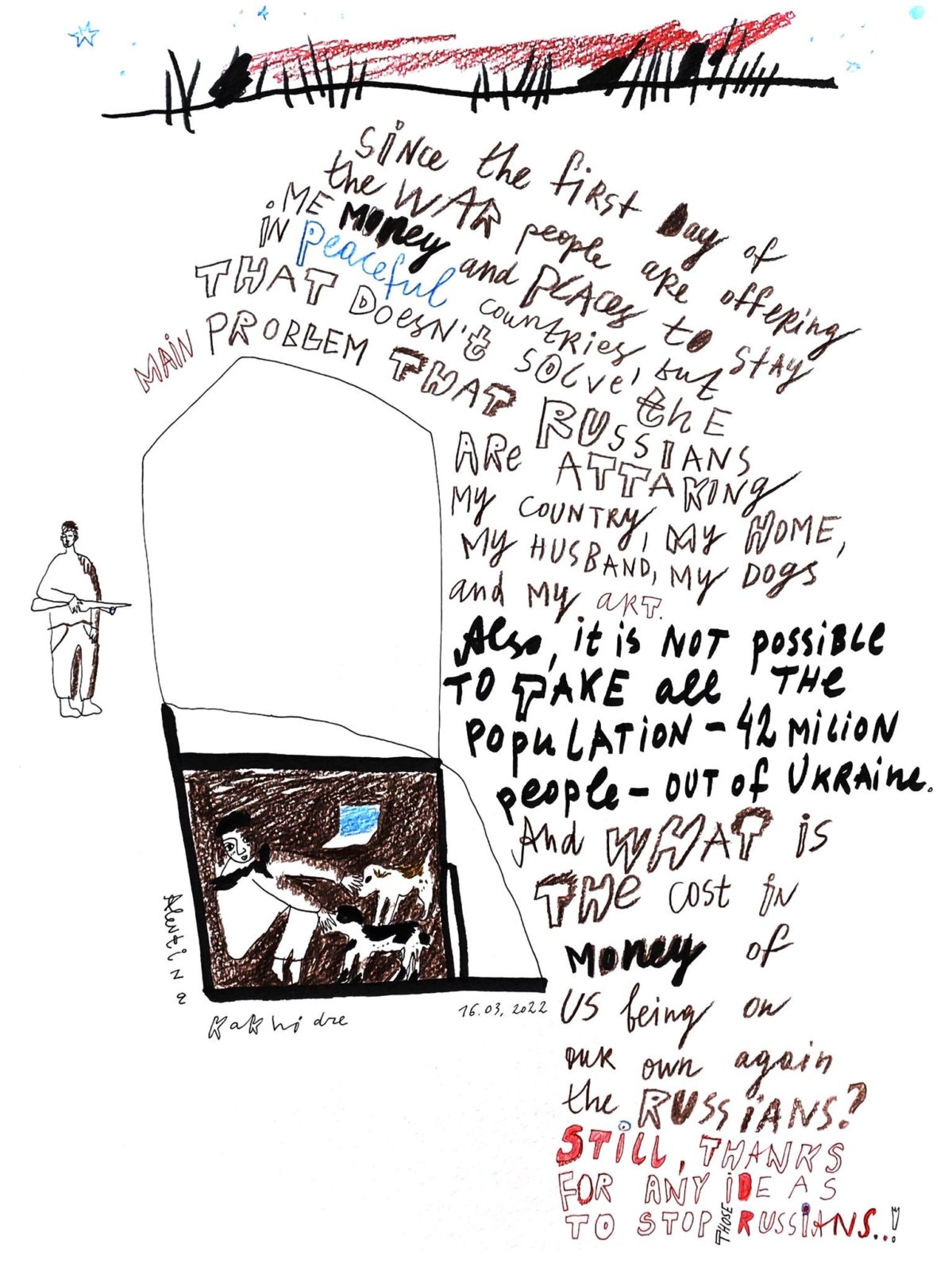

Alevtina Kakhidze is one of the artists to document her experiences since the second day of the war, utilizing her vast international recognition and network all over Europe and in Russia. In her first war drawings – the first pages in her ongoing visual diary published on her Facebook page –, Alevtina tried to call on Russian artists and intellectuals to take to the streets.

Over the next days and weeks, she and her husband in their house in the suburbs of Kyiv with their dogs, enduring shelling and the threat of the possible invasion, her drawings transformed into imprints of her daily experiences. Starting from sleeping in the basement without electricity or internet connection, spanning all the way into visual discussions about the origin of Russian imperialism and the need to decolonize Russian culture.

Alevtina Kakhidze, Cancel Russian culture. 2022, published on Facebook. Image courtesy of the artist Alevtina Kakhidze.

Alevtina, who is also a performance artist, picked up her peculiar visual language of fast drawing, small on-the-go sketches in a previous series of works where she criticized consumer society. But her world changed in 2014 when war became a huge part of her realilty because her mother, as so many other people of age, refused to leave their homes on the occupied territories in Eastern Ukraine.

Phone calls between mother and the daughter, sketches of the mother’s life under the occupation, and other aspects of the war’s political reality built up an extensive visual diary; 2D performances where colorful schematic figures were surrounded by words in different languages – Russian, Ukrainian, English.

Alevtina Kakhidze, Birthday. 2022, published on Facebook, available via Artists for Ukraine. Image courtesy of the artist Alevtina Kakhidze.

These drawings from 2014 on are not sketches for something else, not preparation for the bigger work, as artists’ diaries and sketchbooks often are. They are snapshots of the moment, visual notes, messages mainly to oneself (and then, to others) not to forget, not to let go even if sometimes that’s exactly what one yearns to do..

Maidan, the occupation of Crimea, and the war in Donbas have changed not just the visual language, but the way artists perceive themselves. As many said during, and especially right after Maidan: when the unthinkable and unimaginable was happening, artists turned into regular citizens, activists, human beings doing whatever they could to help the situation. Even more important, however, was that the inner permission ‘to not be an artist’: allowed not to imagine or reflect, let alone represent, but instead collect, record, save, and try to keep reality intact.

Already then, eight years before the full-scale invasion and war unfolded, artists were collecting the evidence of atrocities. The struggle for a visual language to grasp and speak about the reality was an attempt to (re)claim agency and to own the narrative, to dare and see the war and its aftermath with their own understanding, not through the imagery supplied by mass-media or commercial culture, and avoiding the recycling art of other wars or conflicts. The aim has been to build a unique form of expression, one that transcends mere tropes; one that is true to the reality of the here and now.

Peripheral vision

Writing about the frames of war, Judith Butler inquired about how the framing of the image of war through cameras affects the materiality of war and influences public discourse about it. She extensively analyzed how the frame of an image includes and excludes certain parts of a narrative, forming resistance potential on the margins; in those zones of exclusion something is undisclosed and the numbers of casualties are not self-explanatory (1). However, Butler writes about the politics of framing the materiality of war for the external gaze. But what happens on the inside, when the perception is framed by someone’s own eyes? What will fall on a blind spot, what is oushed to the periphery?

For those living the daily reality of this current war, the materiality and violence are framed by the Ukrainan government’s explicit ban on the use of the immediate images of destruction – this ban was introduced for security reasons, however, there is an increasing number of cases of international media and Telegram channels violating this ban.

This experience is complemented by the unspoken expectation of international media to limit the expression of strong emotions. It somehow seems that being openly emotional, like expressing pain or rage, deprives the speaker, regardless of her or his recent experience, of the assumptions of rationality, dignity, and thus of agency and a valid voice.

It is on the margins of this frame that artists often step in.

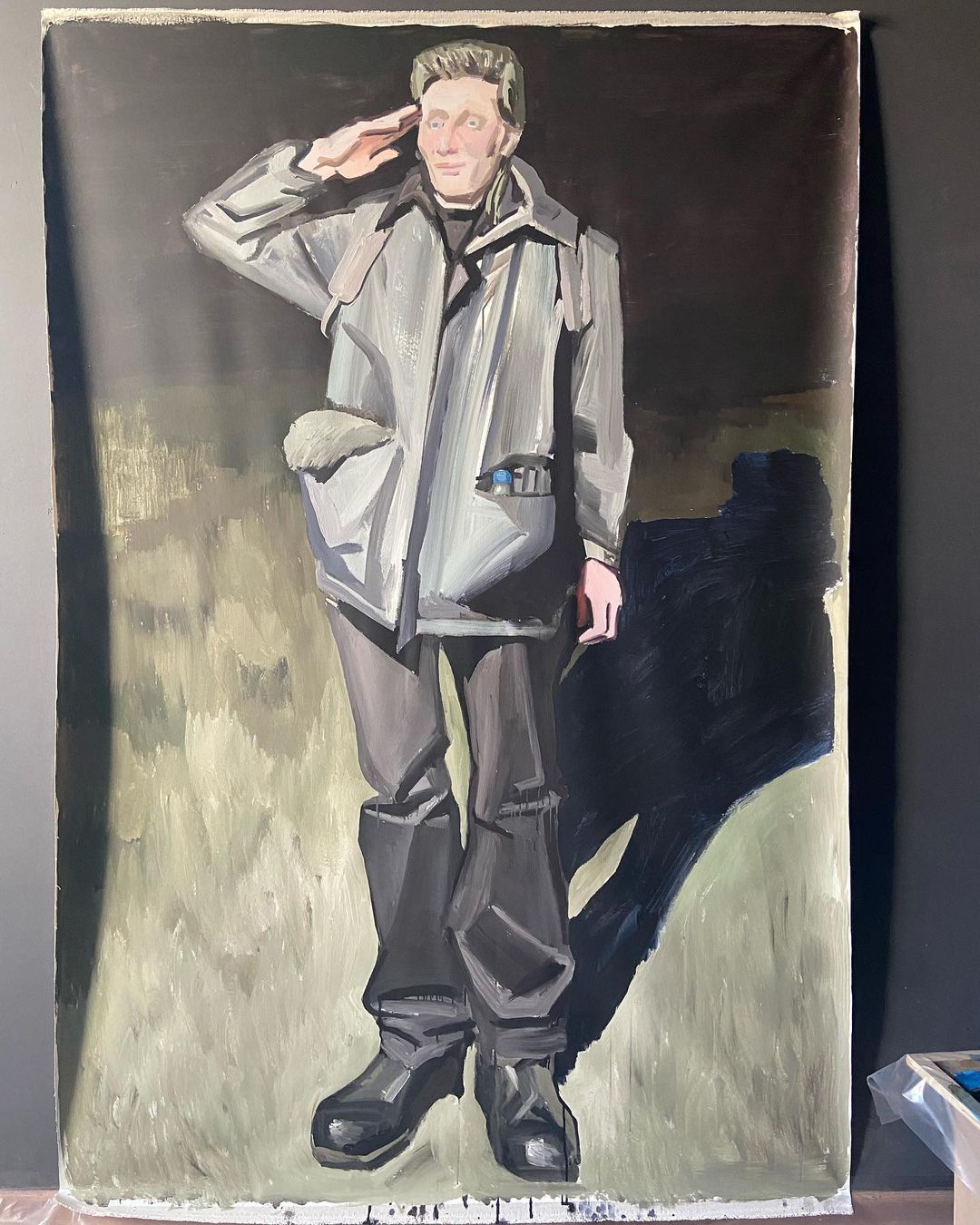

‘My husband, artist and musician @maxrobotov is a lieutenant in the Ukrainian army now. He sent me his photo because I was curious what it looked like. Taking photos of soldiers and military objects is forbidden now in Ukraine because of the war. Before the escalation of the war, I was contemplating the commonalitiesof the military optic and artistic view. Max represents both positions now,’ wrote Lesya Khomenko on her Facebook page in mid-March. Below is her painting of the photo of her husband, bareheaded, in half-military half-civilian clothes, giving military salute. It’s her first work after February 24 and after relocation to Western Ukraine. Somewhere behind the surface of this clearly distanced, even formal painting and behind the artist’s calm words is fear, suffocating fear never to be able to see your loved one again.

Lesya Khomenko’s portrait of her husband, based on a photo, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist Lesya Khomenko.

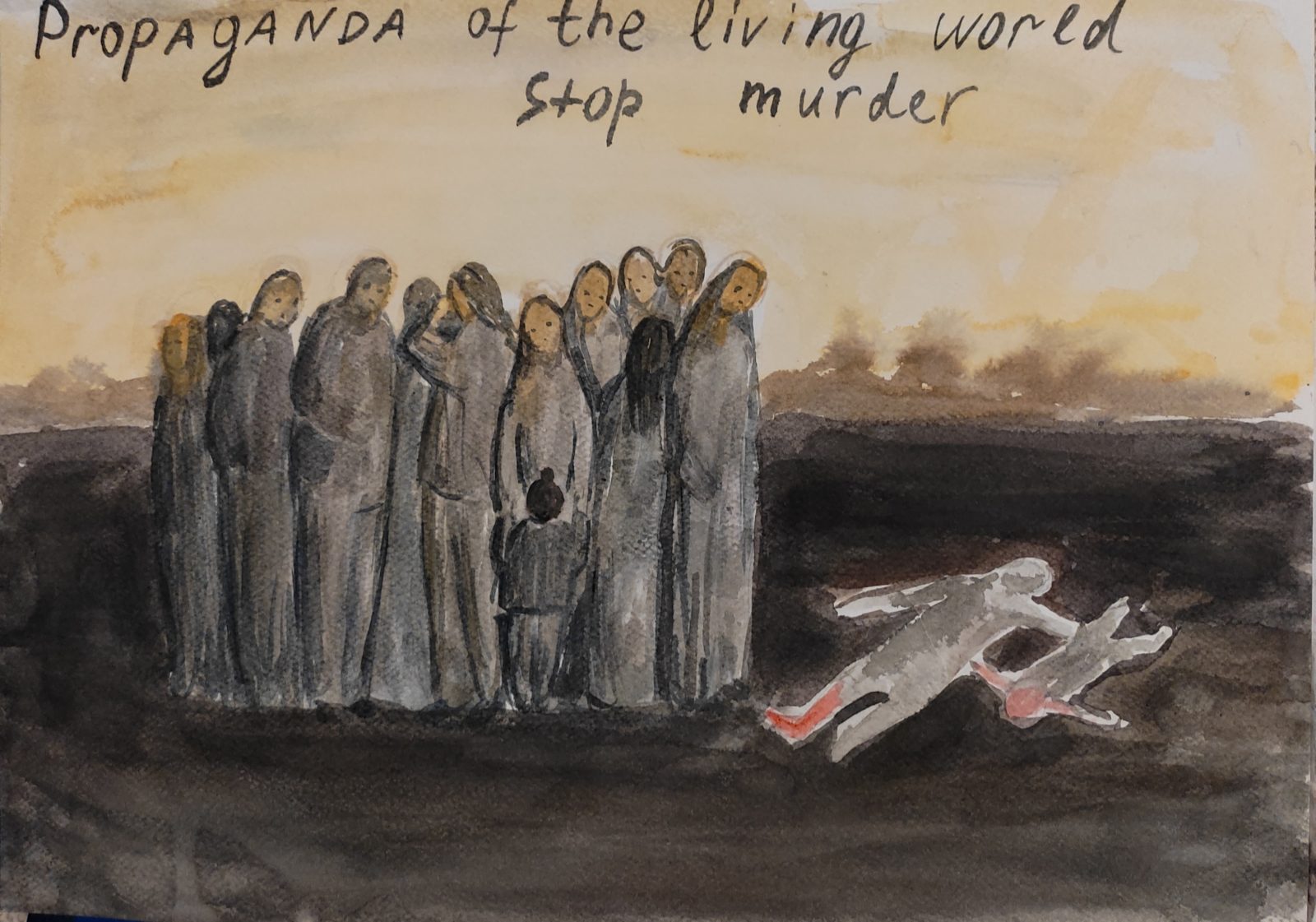

Kateryna Lysovenko spent a few nights in a bomb shelter in Kyiv with her two children and a cat before relocating first to Lviv, then to Poland, and soon to Austria. Lysovenko created a number of smaller watercolours while on the road. Schematic, flat, almost faceless figures stand against the grim background, almost dissolving in it. One of the works says ‘Propaganda of the living world. Stop murder.’

Kateryna Lysovenko, Propaganda of the living world. Stop murder. 2022. Image courtesy of the artist Kateryna Lysovenko.

The living world, human and non-human relations, care for the world but also the care of a mother for her child had been Kateryna’s topics well before the war. Arriving in Poland, lost and disoriented, her children deeply traumatized, she got a residency support from BWA Zielona Góra. There she goes back to large-scale painting: human figures get more shape and sometimes even faces, they are mostly female, carrying or holding, sometimes cradling children. She’s almost back to her usual imagery with a few striking exceptions, however: on most works, the colors are gone or faded, and once in a while, maybe on especially emotionally hard days, the strong corporeality of bodies shrinks again to small, shapeless figures, piled up in a mass graves or spread on the ground, raped, bleeding.

Kateryna Lyvosenko, They Can Repeat. 2022, published on Instagram. Image courtesy of the artist Kateryna Lysovenko.

Accompanying the images of her works on her Instagram, another diary of the war, the artist writes, ‘I carry gardens of sorrow, gardens of anger from irreparable loss, I remember everything that disappears, I want to breathe deeper to accommodate more, I am now a moving cemetery.’

Kateryna Lysovenko, Gardens of Sorrow. 2022, published on Instagram. Image courtesy of the artist Kateryna Lysovenko.

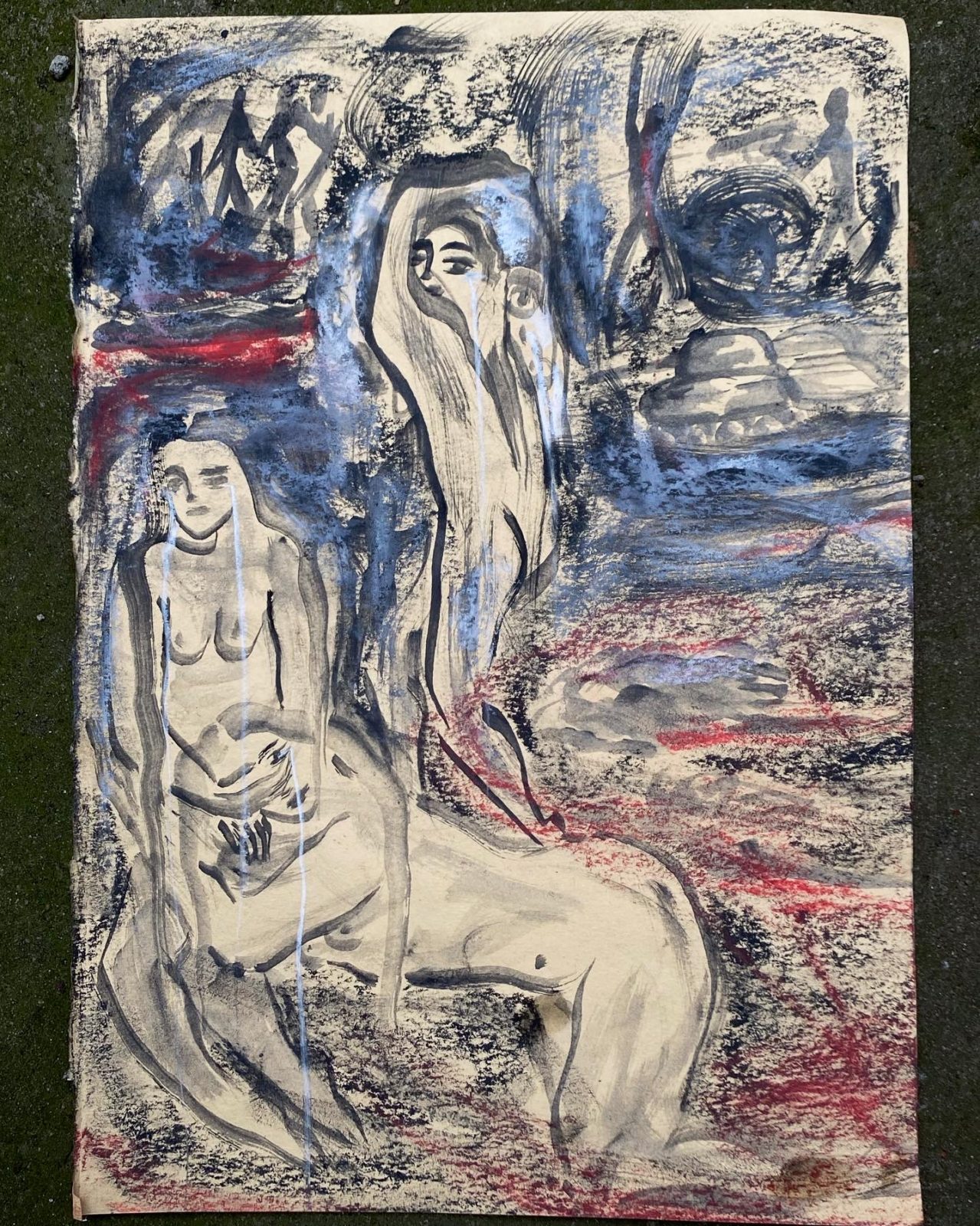

Bodies, shapeless ones looking more like outlines or abstract figurines or more definitively feminine, are one of the main symbols in the imagery of this war. Shapeless ones usually come en masse – in bomb shelters or train stations. Female ones, naked and apparently vulnerable, protect, embrace, or stop the tanks, like in the works of the female artist who works under the alias Kinder Album; iothers grow into and with the nature, turning into birds, animals or vegetation, like in works by Sana Shakhmuradova.

Sana Shakhmuradova: Dedicated to victims (women, children, civilians) raped, tortured, suffered and died because of Russian inhumane attack and violence. 2022, published on Instagram. Image courtesy of the artist Sana Shakamuradova.

The imagery and symbolism of these and many other artists’ diaries are very simple and schematic, lines are fast, colors are rough, emotions are raw. Even if already exhibited somewhere in exile, these works are still mostly meant as notes to oneself, semi-public diaries available on social media, a regular exercise in seeing and feeling without a chance to escape.

They remind of what is seen should never become unseen and what’s been understood can never be dismissed. The overwhelming reality of this war needs to find its way onto the physical surface of paper, canvas, or wall, to stop it from being forgotten.

Kinder Album, Russian Soldiers Rape Women in Ukrainian Cities. 2022, published on Instagram. Image courtesy of the artist Kinder Album.

As for male artists and the male imagery of the war, the silence is even more literal. Many notable artists as well as writers, actors, film directors, researchers, and other intellectuals, voluntarily enlisted either into the army or into the territory defense units. The works they could have drawn, painted, written, filmed, is now covered in the throbbing silence of the war.

Testimonial

International discussions about the role and function of art in the war are tailored to notions like ‘healing’ and ‘peaceful mutual understanding.’Neither of these are expressed in the current works of Ukrainian.

It is testimony, it is the evidence of the tragedy that should have never happened, but indeed it has. It’s a powerful emancipatory work to create a visual language that can grasp these events, the loss, the emotions; to record this particular present in a new, uncomfortable yet distinct voice.

After the first major wave of the pandemic, Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe wrote, ‘fundamental vulnerability is the very essence of humanity (2).’

Art conceived as a daily practice of seeing and enduring is an evidence to this fundamental vulnerability.

(1) Judith Butler Frames of War. When Is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2010)

(2) Mbembe, Achille. ‘The Weight of Life. On the Economy of Human Lives.’ Eurozine. https://www.eurozine.com/the-weight-of-life/. Publication date: 06.07.2020.

“She lost consciousness as it was happening and she’s actually grateful she did.” What we know about the rapes perpetrated in Ukraine by Russian soldiers

“One girl finds it difficult to speak because while she was being raped, her face was beaten, and her teeth were knocked out. In the Ukrainian language, the word for this is гугнявить,” says Ekaterina Galyant, a clinical psychologist from Kyiv, pausing at length.

She is currently in Tallinn, Estonia, working in two local maternity hospitals with refugees from Ukraine – these women aren’t necessarily pregnant, but examinations and consultations are offered to all arriving Ukrainians. Ekaterina has qualifications in both psychology and medicine, so she is “both a doctor and a psychologist” for the refugees.

Three girls that were raped by Russian soldiers – 16, 17 and 20 years old – are not currently in Tallinn. They contacted Ekaterina over social media, two of them having been advised by friends. The psychologist says that she works with them individually over Zoom: her camera is on, the victim’s remains off. Ekaterina does not know their real names and refrains from asking too many questions for now – sometimes the conversation lasts only 5-10 minutes, then the girls start crying and hang up. It’s distressing work for Ekaterina; she says she would burn out if she took on another victim of wartime assault.

“Two of the girls are from Bucha, and one is from Irpen,” Ekaterina Galyant continues. “Naturally, none of their requests literally said: “I was raped, help me.” The women mostly wrote things like: “I see no reason to live,” “I have suicidal thoughts,” “I can’t sleep,” “I can’t eat,” “I hate my body, I can’t even bring myself to touch it,” and so on. One patient with suicidal ideation found me through a channel for volunteers. We spoke over Zoom, at first I was collecting background information. I thought she might be clinically depressed and that I needed to contact a psychiatrist – only later did she tell me that she had been in Bucha and that she had been raped. And from that moment on she has been in therapy.”

All three of the girls’ stories are very similar, says the psychologist. At first it was actually confusing: “I initially thought there’s been a sole perpetrator, some kind of morally perverted monster – there are people like that during peacetime, too. But here they came in groups and all did the same thing! Maybe they had received orders or had some kind of plan… [the victims] are all basically telling the same story.”

The victims’ recollections appear to be divided into three parts, she continues: at first, the girls told her how at the beginning of the occupation the Russian military went аround their homes and noted down who was living there and whether there were men among them, and confiscated mobile phones. Then, they describe how the soldiers began looting; according to Ekaterina, “they even took an iron” from one of her clients. And about a week and a half before their retreat from Kyiv, “the atrocities started”.

“[The Russian soldiers] took all the men, and no one knows what they did to them,” says Galyant. “There were basically only women and children left [in the houses]. The father of one of the three girls was killed during the occupation: he had gone out in Bucha to find groceries and was shot, she said. She never saw the body, but one of the neighbours supposedly did. He never returned, and right now she isn’t even able to look for the body. We haven’t gone near that subject yet.”

All three girls say that the military went round the houses in groups of three to five, of various ages: “Most were young soldiers, under 30, accompanied by someone older, a 45 or 50-year-old. Someone their fathers’ age, roughly speaking” says the psychologist. In the evening they would come into the houses. All the soldiers, as the victims recall, were drunk.

“If there was some kind of booze in the house, they would take it out, sit down in the kitchen, and force the girls to cook and serve something to them – if there was anything to eat in the house. And after dinner, the raping would start” Ekaterina says. “In the girls’ cases [that Ekaterina works with], it only happened once, but it was gang rape. And the more the girls resisted, the more the soldiers… well, one girl had her teeth knocked out, she said that she screamed and tried to scratch their faces and fight back. But a 16-year-old girl against five men…”.

Ekaterina’s 17-year-old client lost consciousness during the rape: “and she’s actually grateful she did.” All three girls managed to escape from their houses when the soldiers who had raped them fell asleep. One of the girls – the one who lost her father – was spotted by a neighbour on the street.

“They took her to some house where there were people hiding in the basement,” the psychologist recounts. “She said that while waiting for the evacuation, they barricaded themselves in the basement and didn’t leave. There were people down there who had already died – there was no food, and they couldn’t take out the corpses. I asked her where they got water from: these are sewer pipes in those basements of old houses, so they made some holes in them and got a little water that way.”

Ekaterina Galyant does not know exactly where the girls who have contacted her are currently located. This is another part of their agreement. While trying to establish their medical background and provide assistance, the psychologist also learned of their physical injuries.

“One girl has abrasions, her arm is hurt badly – not broken but there’s been some severe bruising,” she says. “We’ve tried at the very least to give a rough diagnosis of what she can’t properly describe. Well, she can’t use her right hand. My biggest concern is that none of these girls have been to a gynaecologist yet. They all say that when they had a shower for the first time afterwards, they wanted to wash themselves thoroughly, to scrub off their skin. And that’s what they started doing: pouring alcohol-based solutions into their vaginas… That’s also something that really pains me. I know that two weeks or more have already passed and if they have sexually transmitted diseases or pregnancies, we need to help somehow.”

“She was sitting with a fur coat over her naked body. They had shot her in the head.”

“We have a joint application from the victims of rape aged 14 and over, some of whom are pregnant,” writes Vasilisa Levchenko, a psychotherapist from Kyiv, on her Instagram page, “pregnant by the fucking rapists. To clarify: by the occupiers, the Russian soldiers who stole gadgets and gold from their homes, who searched for a blender or a food processor to bring as a trophy to their wives, and then raped innocent Ukrainian women <…> Between us, we share out requests for help in the team chat. Three for Katya, two for Nina, and Ella takes on the hardest cases, women who are numb and can’t say a word.”

Levchenko told Mediazona that five victims of sexual violence had approached her personally. But even gathering statistics within the ‘Psychological Assistance’project she works with is still impossible: “Every day we receive hundreds of requests, I can’t imagine how we’d begin counting the ones concerning assault.”

Until early April, residents of the Zahaltsi village in the Kyiv region had to hide two young women from the Russian soldiers, as Roman Vagrant explained to Mediazona. When the war began he was in Borodyanka, and he fled to Ternopil with his family. His relatives live in Zahaltsi, the village that had been occupied by Russian soldiers since the beginning of March.

“Alcohol, cigarettes and women – that’s all they cared about.” says Roman. “Two girls had stayed in Zahaltsi. People hid them, because someone told the soldiers that there were women in the village, and they were looking for young women.”

“I heard a single shot, the sound of a gate opening, and then the sound of footsteps in the house,” a woman from a village in the Brovary district, told The Times. “It was [a soldier named Mikhail] Romanov, returning with another man in a black uniform, who looked about 20. I shouted: ‘Where’s my husband?’ They looked into the courtyard and saw him on the ground by the gate. The younger guy pointed his gun at my head and said “I shot your husband because he was a Nazi.”

According to Natalya, her young son hid in the boiler room of the house while the soldiers were raping her. She remembers that the rapists held a gun to her head and made sarcastic remarks about her. They raped her three times. “When they came back for the third time, they were so drunk they could hardly stand,” she recalled. “Finally they both fell asleep on the armchairs. I crawled to the boiler room and told my son that we needed to run away really fast or else they’d shoot us.”

Elena, from the captured city of Kherson, weeps while telling Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty how she was raped by Russian soldiers. She had been tracked down as she was coming back from the shop: “I didn’t even have time to enter the house. They came up from behind me. I didn’t have time to grab my phone. I didn’t have time to do anything. They just threw me on the bed, silently, and took my clothes off without saying a word. At 4 o’clock in the morning they left, just like that. They didn’t talk to each other. They just called me a khokhlushka and a Banderovka. And then said, ‘Okay, we’re expected at the post. We’re off.’”

“He took me to a nearby house,” 50-year-old woman from one of the villages in the Kyiv region told the BBC. “’Take off your clothes or I’ll shoot you,’ he ordered. He constantly threatened to kill me if I didn’t do as he said. Then he started raping me. While he was raping me, four more soldiers came in. I thought I was finished. But they took him away. I never saw him again.”

She describes her rapist as “a young, slender Chechen militant.” Before raping the woman, he took her to the nearby house “at gunpoint”, and when she returned home, she saw her husband had been wounded in the stomach. There was no way to get to the hospital – there was fighting going on – and so the couple took refuge in a neighbouring house, where the husband died two days later. She buried him in the backyard.

After her husband’s death, she found out that another woman had been raped and killed in their village. When the police came to exhume her body after the Russians left, it was found naked, with a slit throat.

When Russian troops left Bucha, a nephew of one of the city’s residents found the body of a murdered woman in the basement under his barn.

“Slumped sitting down, bare legs akimbo, she wore a fur coat and nothing else,” as the New York Times report describes, “She had been shot in the head, and he found two bullet casings on the ground. When the police pulled her out and conducted a search, they found torn condom wrappers and one used condom upstairs in the house.”

“He said I reminded him of a girl from school”

One after another, reports of rape began to appear immediately after the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Kyiv region in late March. Some publications were later removed by their authors, including a post by Ukrainian journalist Alina Dubovska about a nine-year-old girl in Irpin who allegedly was raped and mutilated by 11 soldiers.

“Because of the reaction to this story, I had to hide the post about the family of the girl who was raped and then died from my page,” she explained. — “Partly as a result of the hate spewed in my direction, partly because I decided to reopen it only when the relatives allowed me to publish the evidence, so that no one would have any doubts”.

The violence did not only take place in the Kyiv region. On April 3, Human Rights Watch published a report citing the story of a 31-year-old woman from the village of Malaya Rohan near Kharkiv. One Ukrainian woman who asked not to be named described how, on the night of March 14, a Russian soldier had broken into the basement of a local school where a group of women and children were taking shelter. According to the victim, the soldier took her to a classroom on the 2nd floor and forced her to undress and perform oral sex on him at gunpoint. He slashed her face and neck with a knife: “He said I reminded him of a girl from school.”

Cases of rape have been repeatedly reported by Ukrainian officials. As far back as March 22, Ukrainian Prosecutor General Iryna Venediktova wrote that she had been “receiving reports about sexual crimes committed by the Russian military in the occupied territories”.

She added that one of the two Russian soldiers who raped Natalia, a resident of the village of Bohdanivka in Brovary district, who said that her son was hiding in a boiler room while it had been happening, had been identified. This case was also mentioned in a report by Amnesty International.

“The husband tried to protect his family,” Andriy Nebitov, head of the Kyiv regional police, said of the crime and the investigation. “He was born in 1985, a young man. He was gunned down in his own yard. <…> His wife went home with her child and tried to hide from this violence. But during the evening two men (one of them we have identified as [Mikhail] Romanov) returned to the house after consuming alcohol and under the threat of hurting her three-year-old son and shooting him in the same way they killed her husband, raped her. Apart from Romanov, there was another person, not identified by the investigation. These men were members of the Russian military. They left and then came back three more times. They raped her again, and again. Later she managed to break free and escape”.

The Verkhovna Rada Commissioner for Human Rights, Lyudmila Denisova, spoke in early April about raped children in Bucha: she said a 14-year-old girl was raped by five Russian soldiers, resulting in her becoming pregnant, and an 11- year-old boy was molested “in front of his mother”. Denisova said she also knew of many cases of sexual abuse in other places: one instance is that a group of women and girls had been held in the basement of a house for 25 days, and now nine of them are pregnant.

Oleksandr Vilkul, head of the Kryvyy Rih military administration, also spoke about rapes in Kherson Region: “We are encountering more and more terrible stories. Cases like those of a 16-year-old pregnant girl and a 78-year-old elderly lady in one of the villages near river Inhulets. This is something that can never be forgiven”.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy mentioned “hundreds of rape victims” in his recent address to the Lithuanian parliament: “Including underage girls, very young children… even babies! It is horrible to speak about this, but it is true, it happened”.

Russian authorities dismiss the rape allegations. Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov called the reports of murders and rapes in Bucha “a mendacious provocation” as early as April 5.

“Human psyche has a tolerance limit, beyond that it can endure no more.”

Victims of abuse may keep quiet about what happened to them, especially if they suffer no injuries requiring immediate medical attention, explains psychologist Ekaterina Galyant. She anticipates that over time there will be more and more calls.

For now, Ukrainian victims can call the police, hotlines for psychological support, and the office of the Prosecutor General. There is no official statistics on wartime rape cases in Ukraine, and psychologists are ethically bound not to share information about their female clients with each other or with state agencies, Galyant notes.

“Collecting information about these cases can be quite time-consuming,” says Yulia Gorbunova, a Human Rights Watch researcher in Ukraine who is now studying cases of rape in Bucha and Brovary near Kyiv. – In some conflicts, it took months and sometimes years before the true extent of these crimes came to light.”

“Due to the pervasive patriarchal structure of society, some victims understandably will not tell anyone [that they were raped],” notes volunteer Leonid Romanov, who helps Ukrainian refugee women who have been evacuated to Poland. In Poland, abortion is only possible if the life or health of the mother is at risk, so if needed, volunteers can transfer the young women across the border to other countries where abortion is not an issue. But so far no one has approached Romanov.

However, between March 1 and April 11, 99 pregnant Ukrainian citizens applied to the Polish organisation “Abortion Without Borders”, Anna Prus, a volunteer with the Warsaw-based Abortion Dream Team, told Mediazona.

“We do not ask people why they want to have an abortion, how they got pregnant, where they are from,” Anna stresses. “We are not entitled to that kind of information. People sometimes want to talk to us about what happened around a pregnancy, but it’s really depends on their desire to share the details.”

Ekaterina Galyant argues that rape during the war may cause irreparable damage: “People in wartime situations need psychological help. Post-traumatic syndrome can manifest within three to six months after the traumatic event. That is, we are all not even there now, we are currently in a very acute stage of stress. And no one doubts that all Ukrainians will need this kind of help. Human psyche has a tolerance limit, beyond that it can endure no more – it causes some kind of sickness, depression and other things. And if there is war, and then rape is on top of that – that ruins the psyche utterly.”