‘Why? Why? Why?’ Ukraine’s Mariupol descends into despair

MARIUPOL, Ukraine (AP) — The bodies of the children all lie here, dumped into this narrow trench hastily dug into the frozen earth of Mariupol to the constant drumbeat of shelling.

There’s 18-month-old Kirill, whose shrapnel wound to the head proved too much for his little toddler’s body. There’s 16-year-old Iliya, whose legs were blown up in an explosion during a soccer game at a school field. There’s the girl no older than 6 who wore the pajamas with cartoon unicorns, among the first of Mariupol’s children to die from a Russian shell.

They are stacked together with dozens of others in this mass grave on the outskirts of the city. A man covered in a bright blue tarp, weighed down by stones at the crumbling curb. A woman wrapped in a red and gold bedsheet, her legs neatly bound at the ankles with a scrap of white fabric. Workers toss the bodies in as fast as they can, because the less time they spend in the open, the better their own chances of survival.

“The only thing (I want) is for this to be finished,” raged worker Volodymyr Bykovskyi, pulling crinkling black body bags from a truck. “Damn them all, those people who started this!”

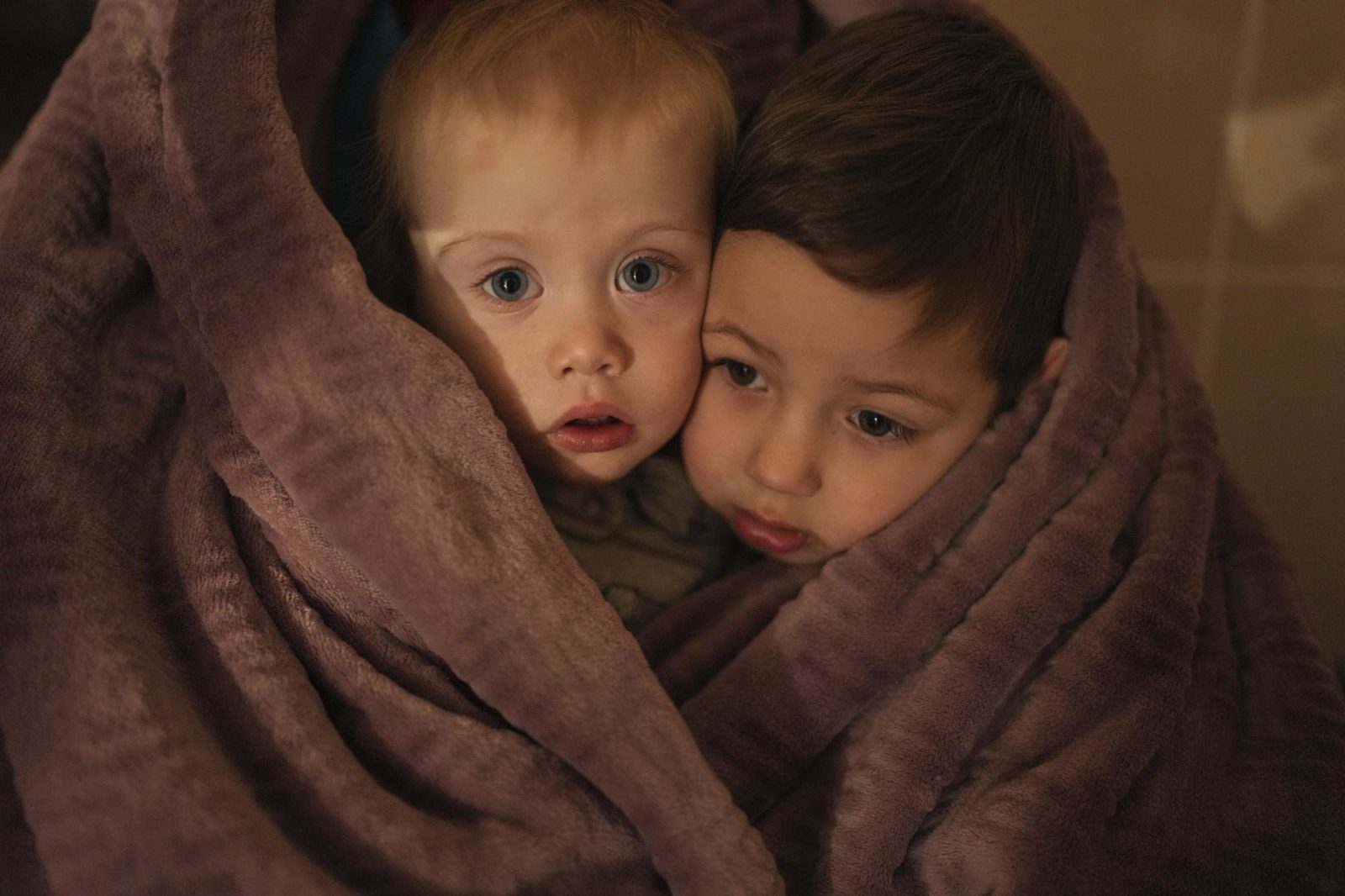

The children of medical workers warm themselves in a blanket as they wait for their relatives in a hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 4, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

An apartment building explodes after a Russian army tank fires in Mariupol, Ukraine, Friday, March 11, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

A body lies covered by a tarp in the street in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

More bodies will come, from streets where they are everywhere and from the hospital basement where adults and children are laid out awaiting someone to pick them up. The youngest still has an umbilical stump attached.

Each airstrike and shell that relentlessly pounds Mariupol — about one a minute at times — drives home the curse of a geography that has put the city squarely in the path of Russia’s domination of Ukraine. This southern seaport of 430,000 has become a symbol of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s drive to crush democratic Ukraine — but also of a fierce resistance on the ground.

In the nearly three weeks since Russia’s war began, two Associated Press journalists have been the only international media present in Mariupol, chronicling its fall into chaos and despair. The city is now encircled by Russian soldiers, who are slowly squeezing the life out of it, one blast at a time.

Several appeals for humanitarian corridors to evacuate civilians went unheeded, until Ukrainian officials said Wednesday that about 30,000 people had fled in convoys of cars. Airstrikes and shells have hit the maternity hospital, the fire department, homes, a church, a field outside a school. For the estimated hundreds of thousands who remain, there is quite simply nowhere to go.

The surrounding roads are mined and the port blocked. Food is running out, and the Russians have stopped humanitarian attempts to bring it in. Electricity is mostly gone and water is sparse, with residents melting snow to drink. Some parents have even left their newborns at the hospital, perhaps hoping to give them a chance at life in the one place with decent electricity and water.

People burn scraps of furniture in makeshift grills to warm their hands in the freezing cold and cook what little food there still is. The grills themselves are built with the one thing in plentiful supply: bricks and shards of metal scattered in the streets from destroyed buildings.

Death is everywhere. Local officials have tallied more than 2,500 deaths in the siege, but many bodies can’t be counted because of the endless shelling. They have told families to leave their dead outside in the streets because it’s too dangerous to hold funerals.

Many of the deaths documented by the AP were of children and mothers, despite Russia’s claims that civilians haven’t been attacked.

“They have a clear order to hold Mariupol hostage, to mock it, to constantly bomb and shell it,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said on March 10.

Just weeks ago, Mariupol’s future seemed much brighter.

If geography drives a city’s destiny, Mariupol was on the path to success, with its thriving iron and steel plants, a deep-water port and high global demand for both. Even the dark weeks of 2014, when the city nearly fell to Russia-backed separatists in vicious street battles, were fading into memory.

And so the first few days of the invasion had a perverse familiarity for many residents. About 100,000 people left at that time while they still could, according to Serhiy Orlov, the deputy mayor. But most stayed put, figuring they could wait out whatever came next or eventually make their way west like so many others.

“I felt more fear in 2014, I don’t feel the same panic now,” Anna Efimova said as she shopped for supplies at a market on Feb. 24. “There is no panic. There’s nowhere to run, where can we run?”

That same day, a Ukrainian military radar and airfield were among the first targets of Russian artillery. Shelling and airstrikes could and did come at any moment, and people spent most of their time in shelters. Life was hardly normal, but it was livable.

By Feb. 27, that started to change, as an ambulance raced into a city hospital carrying a small motionless girl, not yet 6. Her brown hair was pulled back off her pale face with a rubber band, and her pajama pants were bloodied by Russian shelling.

Her wounded father came with her, his head bandaged. Her mother stood outside the ambulance, weeping.

As the doctors and nurses huddled around her, one gave her an injection. Another shocked her with a defibrillator. A doctor in blue scrubs, pumping oxygen into her, looked straight into the camera of an AP journalist allowed inside and cursed.

“Show this to Putin,” he stormed with expletive-laced fury. “The eyes of this child and crying doctors.”

They couldn’t save her. Doctors covered the tiny body with her pink striped jacket and gently closed her eyes. She now rests in the mass grave.

Oleksandr Konovalov, an ambulance paramedic, performs CPR on a girl injured by shelling in a residential area as her dad sits, left, after arriving at the city hospital of Mariupol, eastern Ukraine, Sunday, Feb. 27, 2022. The girl did not survive. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

The lifeless body of a girl killed during shelling at a residential area lies on a medical cart at the city hospital of Mariupol, eastern Ukraine, Sunday, Feb. 27, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

The same geography that for so long worked in Mariupol’s favor had turned against it. The city stands squarely between regions controlled by the Russia-backed separatists — about 10 kilometers (six miles) to the east at the closest point — and the Crimean Peninsula annexed by Russia in 2014. The capture of Mariupol would give the Russians a clear land corridor all the way through, controlling the Sea of Azov.

As February ended, the siege began. Ignoring the danger, or restless, or perhaps just feeling invincible as teenagers do, a group of boys met up a few days later, on March 2, to play soccer on a pitch outside a school.

A bomb exploded. The blast tore through Iliya’s legs.

The odds were against him, and increasingly against the city. The electricity went out yet again, as did most mobile networks. Without communications, medics had to guess which hospitals could still handle the wounded and which roads could still be navigated to reach them.

Iliya couldn’t be saved. His father, Serhii, dropped down, hugged his dead boy’s head and wailed out his grief.

Serhii, father of teenager Iliya, cries on his son’s lifeless body lying on a stretcher at a maternity hospital converted into a medical ward in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 2, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Marina Yatsko, left, runs behind her boyfriend Fedor carrying her 18 month-old son Kirill who was fatally wounded in shelling, as they arrive at a hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, Friday, March 4, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Medical workers unsuccessfully try to save the life of Marina Yatsko’s 18 month-old son Kirill, who was fatally wounded by shelling, at a hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 4, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Marina Yatsko and her boyfriend Fedor comfort each other after her 18-month-old son Kirill was killed in shelling in a hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 4, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

On March 4, it was yet another child in the emergency room — Kirill, the toddler struck in the head by shrapnel. His mother and stepfather bundled him in a blanket. They hoped for the best, and then endured the worst.

“Why? Why? Why?” his sobbing mother, Marina Yatsko, asked in the hospital hallway, as medical workers looked on helplessly. She tenderly unwrapped the blanket around her lifeless child to kiss him and inhale his scent one last time, her dark hair falling over him.

That was the day the darkness settled in for good — a blackout in both power and knowledge. Ukrainian television and radio were cut, and car stereos became the only link to the outside world. They played Russian news, describing a world that couldn’t be further from the reality in Mariupol.

As it sunk in that there was truly no escape, the mood of the city changed. It didn’t take long for grocery store shelves to empty. Mariupol’s residents cowered by night in underground shelters and emerged by day to grab what they could before scurrying underground again.

Serhiy Kralya, 41, looks at the camera after surgery at a hospital in Mariupol, eastern Ukraine on March 11, 2022. Kralya was injured during shelling by Russian forces. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Medical workers treat a man wounded by shelling in a hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 4, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

On March 6, in the way of desperate people everywhere, they turned on each other. On one street lined with darkened stores, people smashed windows, pried open metal shutters, grabbed what they could.

A man who had broken into a store found himself face to face with the furious shopkeeper, caught red-handed with a child’s rubber ball.

“You bastard, you stole that ball now. Put the ball back. Why did you even come here?” she demanded. Shame written on his face, he tossed the ball into a corner and fled.

Nearby, a soldier emerged from another looted store, on the verge of tears.

“People, please be united. … This is your home. Why are you smashing windows, why are you stealing from your shops?” he pleaded, his voice breaking.

Yet another attempt to negotiate an evacuation failed. A crowd formed at one of the roads leading away from the city, but a police officer blocked their path.

“Everything is mined, the ways out of town are being shelled,” he told them. “Trust me, I have family at home, and I am also worried about them. Unfortunately, the maximum security for all of us is to be inside the city, underground and in the shelters.”

People lie on the floor of a hospital during shelling by Russian forces in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 4, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

A Ukrainian serviceman guards his position in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 12, 2022.(AP Photo/Mstyslav Chernov)

And that’s where Goma Janna could be found that night, weeping beside an oil lamp that threw light but not enough heat to take the chill off the basement room. She wore a scarf and a cheery turquoise snowflake sweater as she roughly rubbed the tears from her face, one side at a time. Behind her, beyond the small halo of light, a small group of women and children crouched in the darkness, trembling at the explosions above.

“I want my home, I want my job. I’m so sad about people and about the city, the children,” she sobbed.

This agony fits in with Putin’s goals. The siege is a military tactic popularized in medieval times and designed to crush a population through starvation and violence, allowing an attacking force to spare its own soldiers the cost of entering a hostile city. Instead, civilians are the ones left to die, slowly and painfully.

Putin has refined the tactic during his years in power, first in the Chechen city of Grozny in 2000 and then in the Syrian city of Aleppo in 2016. He reduced both to ruins.

“It epitomizes Russian warfare, what we see now in terms of the siege,” said Mathieu Boulegue, a researcher for Chatham House’s Russia program.

People settle in a bomb shelter in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

A woman holds a baby in a bomb shelter in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 8, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka

People queue to receive hot food in a improvised bomb shelter in Mariupol, Ukraine, Monday, March 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

A man plays with a baby in a bomb shelter in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka

By March 9, the sound of Russian fighter jets in Mariupol was enough to send people screaming for cover — anything to avoid the airstrikes they knew would follow, even if they didn’t know where.

The jets rumbled across the sky, this time decimating the maternity hospital. They left a crater two stories deep in the courtyard.

Rescuers rushed a pregnant woman through the rubble and light snow as she stroked her bloodied belly, face blanched and head lolling listlessly to the side. Her baby was dying inside her, and she knew it, medics said.

“Kill me now!” she screamed, as they struggled to save her life at another hospital even closer to the front line.

The baby was born dead. A half-hour later, the mother died too. The doctors had no time to learn either of their names.

Ukrainian emergency employees and volunteers carry an injured pregnant woman from a maternity hospital damaged by shelling in Mariupol, Ukraine, Wednesday, March 9, 2022. The baby was born dead. Half an hour later, the mother died too. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Mariana Vishegirskaya walks down stairs in a maternity hospital damaged by shelling in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka

Mariana Vishegirskaya lies in a hospital bed after giving birth to her daughter Veronika, in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 11, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Another pregnant woman, Mariana Vishegirskaya, was waiting to give birth at the maternity hospital when the strike hit. Her brow and cheek bloodied, she clutched her belongings in a plastic bag and navigated the debris-strewn stairs in polka-dot pajamas. Outside the ruined hospital, she stared motionless with wide blue eyes at the crackling flames.

Vishegirskaya delivered her child the next day to the sound of shellfire. Baby Veronika drew her first breath on March 10.

The two women — one dead and one a mother — have since become the symbol of their blackened, burning hometown. Facing worldwide condemnation, Russian officials claimed that the maternity hospital had been taken over by far-right Ukrainian forces to use as a base and emptied of patients and nurses.

In two tweets, the Russian Embassy in London posted side-by-side images of AP photos with the word “FAKE” over them in red text. They claimed that the maternity hospital had long been out of operation, and that Vishegirskaya was an actress playing a role. Twitter has since removed the tweets, saying they violated its rules.

The AP reporters in Mariupol who documented the attack in video and photos saw nothing to indicate the hospital was used as anything other than a hospital. There is also nothing to suggest Vishegirskaya, a Ukrainian beauty blogger from Mariupol, was anything but a patient. Veronika’s birth attests to the pregnancy that her mother carefully documented on Instagram, including one post in which she is wearing the polka-dot pajamas.

Two days after Veronika was born, four Russian tanks emblazoned with the letter Z took up position near the hospital where she and her mother were recovering. An AP journalist was among a group of medical workers who came under sniper fire, with one hit in the hip.

The windows rattled, and the hallways were lined with people with nowhere else to go. Anastasia Erashova wept and trembled as she held a sleeping child. Shelling had just killed her other child as well as her brother’s child, and Erashova’s scalp was encrusted with blood.

“I don’t know where to run to,” she cried out, her anguish growing with every sob. “Who will bring back our children? Who?”

By early this week, Russian forces had seized control of the building entirely, trapping medics and patients inside and using it as a base, according to a doctor there and local officials.

Orlov, the deputy mayor, predicted worse is soon to come. Most of the city remains trapped.

“Our defenders will defend to the last bullet,” he said. “But people are dying without water and food, and I think in the next several days we will count hundreds and thousands of deaths.”

Anastasia Erashova cries as she hugs her child in a corridor of a hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 11, 2022. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

The long road to a home in Europe

It is one of many boats making the crossing to Europe. On 1 August 2016, 118 migrants are rescued from the waters of the Mediterranean. They are attempting to cross from Libya to Italy, in a dinghy that is slowly filling up with water. The men – all are men – are mainly from West African countries such as Guinea, Senegal and the Gambia.

They use a migration route that is busier than ever in 2016. Due to the deal of 18 March 2016, the border between Turkey and Greece is hermetically closed. As a result, migrants are opting for the much longer crossing from Libya to Italy. Since the fall of Gaddafi and the war in Libya, human traffickers there can go about their business fairly unhindered. But it is a dangerous route, on which 4,576 people die that year – making 2016 the deadliest year in the history of migration to Europe.

At the same time, 181,436 people are rescued that year, mostly by private aid workers, and land in Italy. They dominate the news and disrupt politics, all across Europe. Most of these boat migrants are among the “fortune seekers” despised by right-wing politicians: they left their country not because of war, but because of poverty and a lack of prospects. Often, when they left, they did not intend to travel all the way to Europe. Yet that is where they would disembark in 2016.

Spanish-Iranian journalist and photographer César Dezfuli, who regularly works for de Volkskrant, wants to show the people behind these numbers. He photographs all the migrants from this one boat, just after they have been rescued – their tired, drained, pained faces, scarred by the horrors in Libya, and by the journey between death and life last night.

Later he realises these pictures do not show who these people really are. Where are they now? How are they faring in Europe? And what does Europe look like through their eyes?

Dezfuli embarks on a quest. Through Facebook, he finds one of the people who was on board the dinghy. That one turns out to be in touch with some of the others, and so the photographer proceeds from one to another. He has since traced and photographed 72 of the 118 migrants. For the final eight, Volkskrant journalist Maartje Bakker joined him.

The migrants appear to have spread across large parts of Europe. They have crisscrossed the map of Europe, driven by casual contacts, numbers they have stored in their phones. Forty of them are still in Italy. More than thirty ended up in France. Others travelled on to Spain or Belgium. Some of them were in the Netherlands for a while, though none stayed here.

These men hold up a mirror to Europe. For although they are not wanted here, there appears to be plenty of work for them. In the north, they are earning very reasonable wages with jobs in industry or construction – that is, as long as their asylum procedure is ongoing, because after that they have to leave. In the south, there are also opportunities to find work without residence papers: a migrant in Italy, Spain or France can work in fruit and vegetable growing or construction, if necessary by renting someone else’s ID.

However, this is often not the end of their troubles. Life in Europe turns out to be much more complicated than many imagined. After all, those without papers have no right to exist in Europe. Yet these migrants are not giving up. They keep themselves going, send money to their families, help ensure that siblings can go to school and family members can pay for healthcare. These men, so often maligned in public discourse, show how resilient a human being can be.

And occasionally they manage to find a way up, out of that parallel reality of illegal migration, to a European life in the light of day. Perhaps through a lucky encounter with a woman, or with a Spanish or Italian boss who offers a work contract, or thanks to a lawyer who went the extra mile to arrange a residence permit.

Such an outcome is only fair, these migrants feel, after all they have endured – the only just end to their odyssey.

Neboth: “You should try to erase your memories. Don’t think about the past”

When Neboth boards the rescue ship on 1 August 2016, there is no relief or joy on his face. He is looking worried. Yes, he has reached Europe. But without his wife Joy, with whom he left Nigeria.

In his homeland, Neboth (now 36) worked as a decorator of weddings and other events. Wistfully, he thinks back to the house he grew up in, a spacious four-bedroom home. “We always put flowers outside,” he says. “I watered them and took out the bad ones in the morning.”

He has a fickle nature, sometimes calm and rational, other times angry and short-tempered. One day, he decides to leave Nigeria, hoping for a better life elsewhere. His daughter stays behind with his parents. “All the money I earned there, I spent on food,” he says. “And you don’t always have electricity in Nigeria, no good roads or schools, there are not enough hospitals. If Nigeria only had 10 percent of what Italy has, I would have stayed there.”

Neboth and his wife travel together until they, after a trip across the desert, arrive in the city of Sabha in Libya. “There they took my wife, while putting a gun to my head,” he says flatly. “If I had said anything, they would have shot me dead. It is better to stay calm, tranquilo. In Nigeria, we say: a live dog is better than a dead lion.”

Wherever he goes in Libya, he looks for his wife, but he does not find her. After six months, he decides to make the crossing to Europe alone. During the weeks before the attempt, he is living in a camp with other migrants in the dunes near Sabratha. There, he tries to recreate something of the homely life of the old days, by making himself a kind of private room. He stacks concrete blocks on top of each other and fashions a canopy out of rubbish. His room is so low that he can only lie in it, but here he can keep his things and have some privacy.

From the crossing, Neboth remembers having to take off his jacket to mop the water out of the boat. “We mopped and gave the clothes to those at the edge of the boat to wring them out,” he says.

Once in Italy, he is taken to Senigallia, a town on the Adriatic coast. After six months, he manages to get his wife’s phone number. He calls her and learns she is in Tripoli. “She was doing okay,” he says. What was she doing in Libya? “That’s not something to reveal in public.” Neboth sends his wife money for the crossing.

Neboth’s application for asylum in Italy is rejected. He travels to Switzerland, but is sent back within a few weeks. And so he is still in Italy, illegally. First he works in Sardinia, painting luxury yachts in shiny white. The ships are sold for millions; Neboth gets €700 a month for his labour. After two years, when the police start asking around about illegal workers at the shipyard, his boss tells him to leave.

Neboth ends up in Matera, a town in southern Italy, famous for its cave dwellings and early Christian churches. But that is not the Matera that Neboth gets to know. He lives in a house with other Nigerians on an industrial estate. In his room, which he rents for €200 a month, he has again tried to make himself at home. The wall is decorated with plates, and a picture of plants and butterflies. An air freshener occasionally sends out a puff of pleasant rose scent.

But right outside the front door, the raw reality begins. There are piles of stinking rubbish. Stray cats make themselves comfortable on an old car seat and a sofa.

During the day he works, still illegally, at a Chinese company that makes chairs and sofas. Neboth upholsters four or five pieces of furniture per day – Made in Italy. “These Chinese don’t care if we get sick, if we die,” he says. “If you come, you get €25 a day. And if you don’t come, nobody cares.”

Sometimes he is close to despair. “I work all day, but at night I can’t sleep,” he says. His eyes shoot back and forth restlessly. He constantly receives calls from people from Nigeria, begging him for money. He cannot understand why Italy does not give him a residence permit. “Some people have documents, but they don’t see any work they can do. They keep begging. I see work everywhere, even without documents!”

His wife made it across and these days lives in Rome. Sometimes they visit each other. She looks after an old lady with whom she lives. About the past he thinks as little as possible – the horror of what happened in Libya, the crossing, his failed attempts to build a life. “You should try to erase your memories,” he says. “Don’t think about the past. Now is now. It’s better to look to the future.”

What does that future look like? One day, he hopes to live with his wife and daughter again. “In Nigeria, we had a good life,” he says. “That is what I would like to rebuild here too. My dream is to live like any normal person.”

Oumar: “Even with a degree, my eldest brother still earned very little. That’s why I wanted to go to Europe”

It is thanks to two ruses that Oumar is on the boat that was rescued off the coast of Libya on 1 August 2016. His name was not on the list drawn up by the people-smugglers for this crossing. But he raised his hand after Diallo Boubakar’s name was called out and no one else responded. “Why the hesitation?”, he is asked. “I was dozing,” he says.

Once on the beach, he has to be inventive again. Diallo Boubakar may be on the list, but at the very bottom – and there is often no room on board for the last ones.

So once the Zodiac is in the water, and when everyone is queuing on the beach to board, Oumar hides behind the boat, in the water. Only his head rises above the waves. It is night, so no one sees him.

During the boarding there is a commotion. That is when Oumar emerges beside the boat, holds out his hands and is helped on board. Plan succeeded.

Alpha Oumar (now 28) – called Oumar for short by his friends – is from Guinea. Until the age of 20, he went to school. His father, a schoolmaster, wants him to study, to become a journalist, because he loves writing. “But I saw that my eldest brother was still earning very little with his degree,” he says. “That’s why I wanted to go to Europe.”

After some wanderings through Algeria, Morocco and Libya, he finally reaches Europe in August 2016. The Italian authorities take him to Carovigno, not far from Brindisi. Oumar, a thoughtful and deeply religious young man, assiduously attends Italian classes six days a week. Sometimes he goes to Brindisi for it, sometimes the lessons are at the reception centre. He makes rapid progress and practises his new language with the staff at the shelter.

His asylum application is rejected. Oumar knows he is faced with an important choice: which lawyer to hire? Three work at the reception centre. He chooses a man who has just started his law practice. “He will try extra hard,” he thinks, “because he has yet to establish his name.”

And indeed, he is lucky, as are about one in three asylum seekers in Italy: his application for a residence permit is granted. After one year and five months, Italy grants him asylum on humanitarian grounds, and he is allowed to work legally. Why him and not others? That is a matter for conjecture. Maybe it is the lawyer, maybe his Italian fluency, maybe the story he tells to the asylum commission. Maybe the fact that he brings along and shows all the things he has written in Italian.

In any case, it seems to be more than just a matter of chance: if you listen to the stories of a number of migrants, after a while you begin to discern a pattern. Those who did more than a few years of school in their home countries, and who had higher social status, often also seem to be able to find their way better in the European bureaucracy. Besides chance, abilities can determine fate.

Be that as it may: Oumar is crying tears of joy. He is transferred, residence permit and all, to Palagiano, the “clementine capital” of southern Italy. There he starts picking clementines and tangerines, and olives. He earns about €1,000 a month, sometimes more.

With five other migrants, he shares a house that they rent for €370 a month. For that, they have to put up with mouldy ceilings and draughty window frames. Sometimes he still writes, just for himself. He keeps his notebook in his bedside table, over which the occasional cockroach scuttles. There are stories and poems, in Italian and French.

When I was born I was black. When I grew up I was black. When the sun shines I am black. When I die I will be black. I am always black, and you are a white man. When you are born you are pink. When you stay in the sun you are red. When you are cold you are blue. When you are scared you are green. When you are sick you are yellow. When you die you will be grey. So tell me who’s a person of colour.

Oumar is not satisfied with his job in agriculture: “This is not what my father dreamed of.” He would like to have another job, an occupation where he can write – and if that’s not possible for him, then maybe for his wife?

He married her in 2019, during his only trip so far back to Guinea. He knows her from before, he would see her walking by whenever she went to school. “I love her very much,” he says, with a smile. “Every day we talk to each other.”

Oumar is trying to arrange for his wife, who is several years younger than him, to come to Italy. He is looking for a house for them together. And he hopes she will then be able to continue her studies. Literature – wouldn’t that be nice?

Modou: “It’s better to stay in one place. Then you get to understand things”

Modou sits in the boat close to the captain. He is in charge of the compass, although he had never seen such a thing before boarding. The Senegalese man has emerged as the leader of a band of migrants. It suits his character: he talks easily, to everyone, and also speaks a little Arabic, learned at Koranic school.

They sail north until they know they are far enough off the coast of Libya. “A plane flew right over us,” says Modou. “That’s when I knew we were in Italy.”

Modou (now 25) worked in Dakar as a clothes seller. Especially women’s clothes, “because women always want to look neat”. Just before he left, he visited his mother one last time, in the village where he grew up. “I didn’t tell her I was going,” he says. “But I did bring her lots of things, things like milk and rice, because I knew we wouldn’t see each other for a long time.” As soon as he crossed the border into Mali, he called her to tell her he has left. It is also the first thing he does in Italy: buy credit and call his mother. She is happy to finally hear from her son. “Thank God, she said, you are alive .”

The Senegalese knows from the start where he wants to go: to Spain, where some relatives and acquaintances live. “I always heard people talking about Spain,” he says. “I tried to listen carefully. I heard that you can live well there.”

After being plucked from the sea, he is first taken to a shelter in Italy. He ends up in the villages of Camerino and Serravalle, in the Marche region. “You couldn’t do anything there,” he says. “Just sit and wait.” He is, however, a keen attendee of Italian classes. “I want to be able to ask things,” he says. “If you don’t understand anything, you’re always scared.”

Serravalle is right in an earthquake zone. “We didn’t know that at all,” Modou notes. “In Africa, you don’t have earthquakes.” After a year, when the earth starts shaking for the umpteenth time, he decides to move on – to Spain. At the border near Ventimiglia, he pays a trafficker and travels by train to France without much trouble. Then he continues by bus to Barcelona. “I carried a book in French and pretended to be reading,” he grins. “That way, everyone would think I was a student.”

In Spain, he soon finds himself in Tàrrega, in Catalonia. Here, too, he plunges into the local language. “I already have eight diplomas,” he says. In a bar, he meets a young Spanish woman who has travelled extensively in Africa. She offers to register him with the municipality at her address. It is an important step towards recognition in Spain: migrants who have been registered for three years, and can show a work contract, are granted a residence permit. Such schemes for economic migrants also exist in other southern countries: those who work and integrate will, over time, have a chance of getting residence papers.

For Modou, the three years in Spain are now over. In the meantime, he has moved to La Fuliola, a village in the same region, among apple orchards. There, he shares an old house with as many as 20 other migrants. Its beautiful modernist floor disappears under the mattresses they sleep on at night. In summer, African migrants flock to this region to pick apples. For Modou too, it is easy to find work during those months.

But when the others leave again, he stays. “It’s better to stay in one place,” he says. “Then you understand things better, and you can get to know people.” Throughout the year, he does odd jobs for nearby farmers. They call him to feed their calves, to give them shots, to help with repairs. Sometimes he gets paid for it, sometimes not. “No pasa res,” he says. It’s no problem, in Catalan – another language he wants to master because “otherwise it would be racist”. In Modou’s words: “You have to persevere, and then you might get lucky.”

He’s right. He now has his residence permit.

Mollow: “The choice is: die here or return to Guinea”

The moment he boards the German rescue ship, Mollow’s face is serious. He is thinking about his sister. Not five minutes pass, he says, that he does not think of his sister. She has told him not to go to Europe. The crossing is too dangerous. “But I was ready to die at that moment,” says Mollow, “after everything I had been through in Libya.”

Mollow is 27, but his frizzy hair is already turning a little grey. “In my whole life, I’ve only had three or four happy years,” he says. In fact, he does not want to think back on everything he has been through. His story consists of disconnected scraps.

From the very beginning, his life was difficult: Mollow was born “out of wedlock”, the son of a Guinean father and a Sierra Leonean mother. His parents met when his father worked as a doctor in Sierra Leone during the war. Two children would be born there: a daughter, then a son.

Mollow grew up in Conakry, Guinea. He never went to school, instead selling things on the street. When he was 12, his mother died, and from then on his sister looked after him. His father’s family did not like him much, and he was even threatened by a friend of his father’s, a military man – at least, that is the story he tells. In 2011, he decides to leave Guinea: the beginning of a long quest, through Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Cameroon. Then to Algeria, after that Libya. And finally to Europe.

In Italy, he stays only two weeks before travelling on to northern Europe. “I don’t speak the language there,” he explains. “That’s why I wanted to go to a French-speaking country.” Although he never went to school, and grew up speaking Susu, he is proficient in French. He learned it along the way.

He takes the train to Rome, to Ventimiglia, to Nice. There are no checks at that point. Then straight on by train to Paris. “I don’t like France,” he says, without being able to properly explain why. He takes a Flixbus to Brussels. Arriving at one in the morning, he spends the night at Brussels North station. In the morning, he reports to the police to apply for asylum.

In Belgium, he lives in a reception centre until, after a year and a half, he is told he has no right to asylum. Mollow decides to travel on to Germany. In time, he finds work there in a car parts factory, in the Ruhr region. Proudly, he shows the wages that were deposited into his bank account, amounts around €2000. He lives in a container house all to himself. The years in Germany – those are the happy years.

Meanwhile, his sister in Guinea is in a bad way, suffering from mental illness. But with the money he earns in Germany, Mollow is able to buy medicine for her, and pay for admission to a psychiatric hospital.

Then, after four years in Germany, he loses everything. Reporting to the German authorities to extend his residence permit, Mollow is taken into custody at a detention centre. The boss of the company where he works sends a letter to the police; he would like to keep him as a labourer. To no avail. Mollow is deported to Belgium because, according to European rules, he can only apply for asylum in one country.

For a place to sleep, he now depends on friends: Guineans from the shelter in Belgium, or others he met elsewhere on his journey. This is how he ends up in Seraing, a suburb of Liège. The dominant colour there is grey – the sky, the boarded-up houses. On the horizon are the rusty remains of a steelworks. Long ago the Lion of Waterloo was cast here.

For four months now, he has been wandering from one address to another. “I’m so tired,” he keeps saying – a European would probably say depressed, but how often is that diagnosis made in Africa?

The money has run out. Mollow reveals where he sleeps: at an acquaintance’s house on the floor, in an unused corner of the shag carpet by the fireplace. He also depends on friends for food. Because he could no longer pay the bills, his sister had to leave the psychiatric hospital. She is now in a village in the care of a traditional healer, who ties her up when she has a seizure. Mollow sometimes hears her screaming over the phone.

More and more often he thinks about going back to Guinea. He is still afraid of the soldier who once threatened him, and who is now said to be high up in the army. Apart from his sister, he has nobody there. Following his mother, his father also died. “But at least I know my sister loves me,” he says.

Actually, he says, he is now at the same point as when he took the boat to Europe. “Then the choice was: suffer in Libya or die at sea. Now it is: suffer here or return to Guinea.” His eyes are filling up with tears.

Kaba: “Life is a ladder. You just have to be patient”

The boat is full, and Kaba is still on the beach. No, he thinks, this is not possible, I have to get in. But when the Guinean tries, the Libyans pounce on him. He hits back, pushes them away, and runs into the water. He dives under the boat, to the other side. There the others help him on board. He is shaking from the stress, the cold. Don’t tremble, they tell him – that way they will know it was you.

Of the crossing, Kaba remembers most of all the pain: he has to sit on one of the big screws sticking up from the bottom of the Zodiac. “In the eyes of Arabs, we blacks are donkeys, worth nothing at all,” he says.

In Italy, Kaba is taken to a shelter in Macerata Feltria, not far from the microstate of San Marino. There, he pulls out the €100 he had sewn into his pants. Since his time in Algeria, where he worked in construction, he has hidden the money there. Somehow he was not robbed of it in Libya.

Without seeking asylum in Italy, Kaba travels on to France after a few weeks, courtesy of the €100. “I don’t speak Italian, but I speak French well,” he explains. He crosses the Italian-French border on foot, along the railway tracks, ducking away when a train passes.

When he arrives in Paris, he asks around among other Africans: where can he go? A passer-by tells him to go to the 18th arrondissement, to the Porte de Clignancourt. There is a big market, where people might give him something to eat.

It is in that neighbourhood that Kaba lives on the streets, for months. During the day he stays in a park, but at night it is closed and he is condemned to the sidewalk. In the morning, he often takes the metro, line 4 from Porte de Clignancourt to Bagneux and back, sinking into a seat to try to get some sleep.

He can’t find work, you need contacts for that. So he begs for food. Sometimes he looks in a bin for discarded clothes, and sells what he finds there at the big flea market for a euro or a euro and a half.

One day, he meets a man from Ivory Coast who has squatted a house and offers him a room. “Then I slept for four days straight,” Kaba says. “I woke up, had breakfast, and fell asleep again.” The Ivorian advises him to apply for asylum. From then on, the French government gives him a living allowance, €380 a month, as long as the asylum procedure is ongoing. But after eight months, his application is rejected. Kaba receives an order stating that he must leave the country.

Again, he has to rely on chance contacts. He meets a compatriot who lives in Montauban, near Toulouse. The man is willing to give Kaba accommodation. So he ends up in the small town on the Tarn, where French people live in one neighbourhood, and Arabs and West Africans in another. “On the first day I went to the café, and there was an Arab who asked: do you want to work?”, Kaba recounts. “I said yes, of course. Then I got to work, picking apples and kiwis.”

From then on, the paid jobs string together. Always undeclared, without a contract. He currently works in construction, as a bricklayer. For every day he works, he gets €50 – a lot more that the €150 he got in Guinea for a whole month

Sometimes France is seen as a country where job contracts are gold-plated and workers’ rights are cast in concrete. In Montauban, that turns out to be only a small part of the story. France, like Italy and Spain, has a large informal economy, in which much of the work is done by migrant workers who have no papers and thus no rights. They pick the fruit, build the houses, and even keep the fast-food chains going. For a while, Kaba sold tacos, a fatty French snack, under the name of a friend who has a residence card – in return for a part of his earnings.

Kaba has not yet given up hope of getting a residence permit. There are three options. Get a work contract, together with a work permit. Conceive a French child. Or marry a French woman. He tries them all. He often goes dancing, on Saturday nights, so as to hit on women. “And I always look neat, in clean clothes,” he says.

Now, when Kaba walks down the street in Montauban, he is constantly greeting acquaintances. One offers a cigarette, which he picks with his teeth. “Ça va bien? Tranquille?” Gone are the days when he slept on the streets. “Life is a ladder,” he says, optimistically. “You just have to be patient.”

Translation by Voxeurop.