What happens after publication?

Three award-winning investigations revisited months later to examine how power adapts, what changed, and why journalism must stay with the story.

The moment a story is published, it begins to change. Sources go back to their lives, systems absorb or resist what has been revealed, readers carry fragments of the work into places the journalist will never see. Some stories trigger big consequences, others leave quieter traces.

After the initial moment of celebration had passed at our Award Ceremony in Bari, we returned to three projects recognised last year to understand what remained once attention moved on, how these stories continued to live, where they stalled, and what they still ask of us.

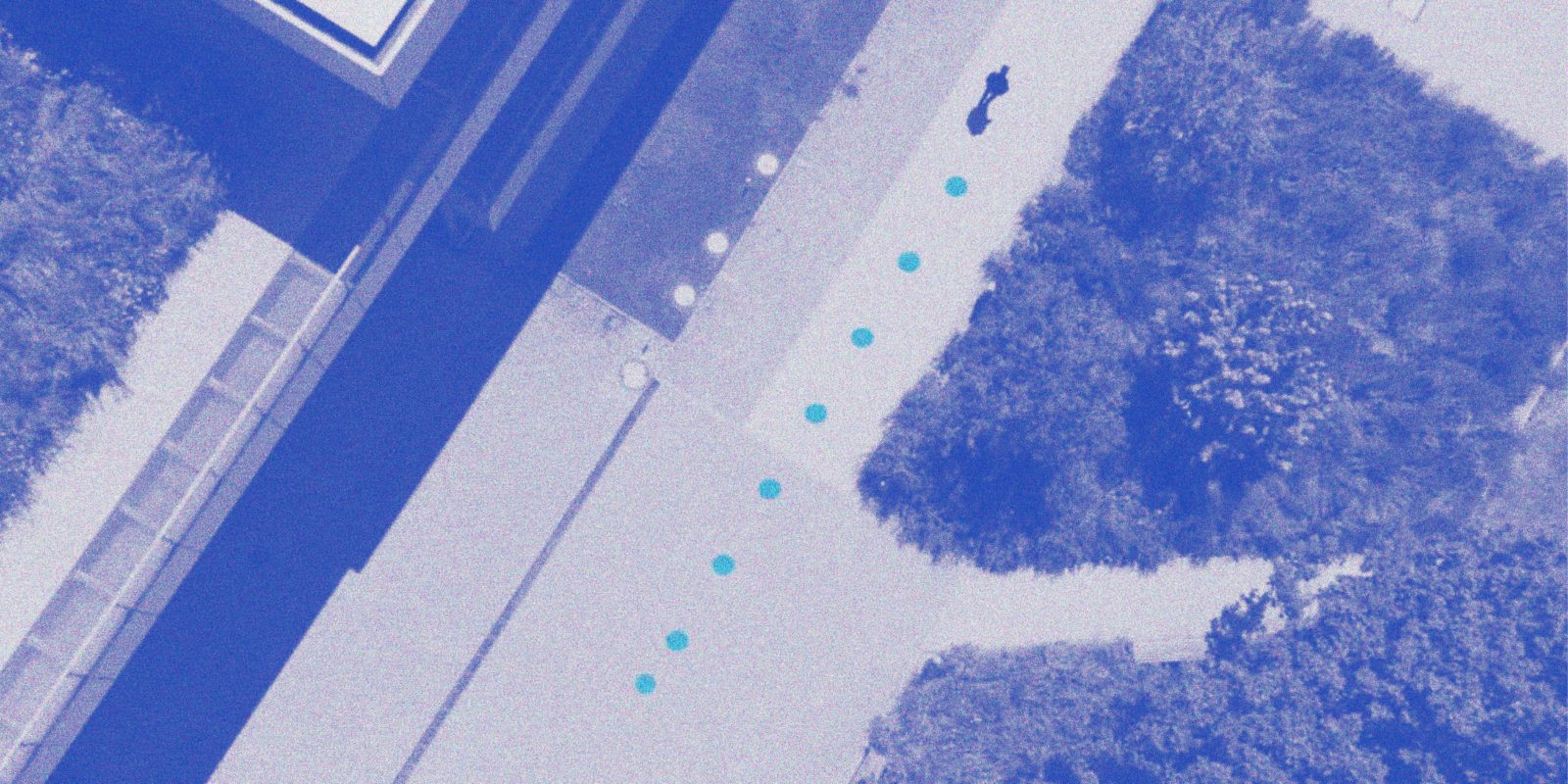

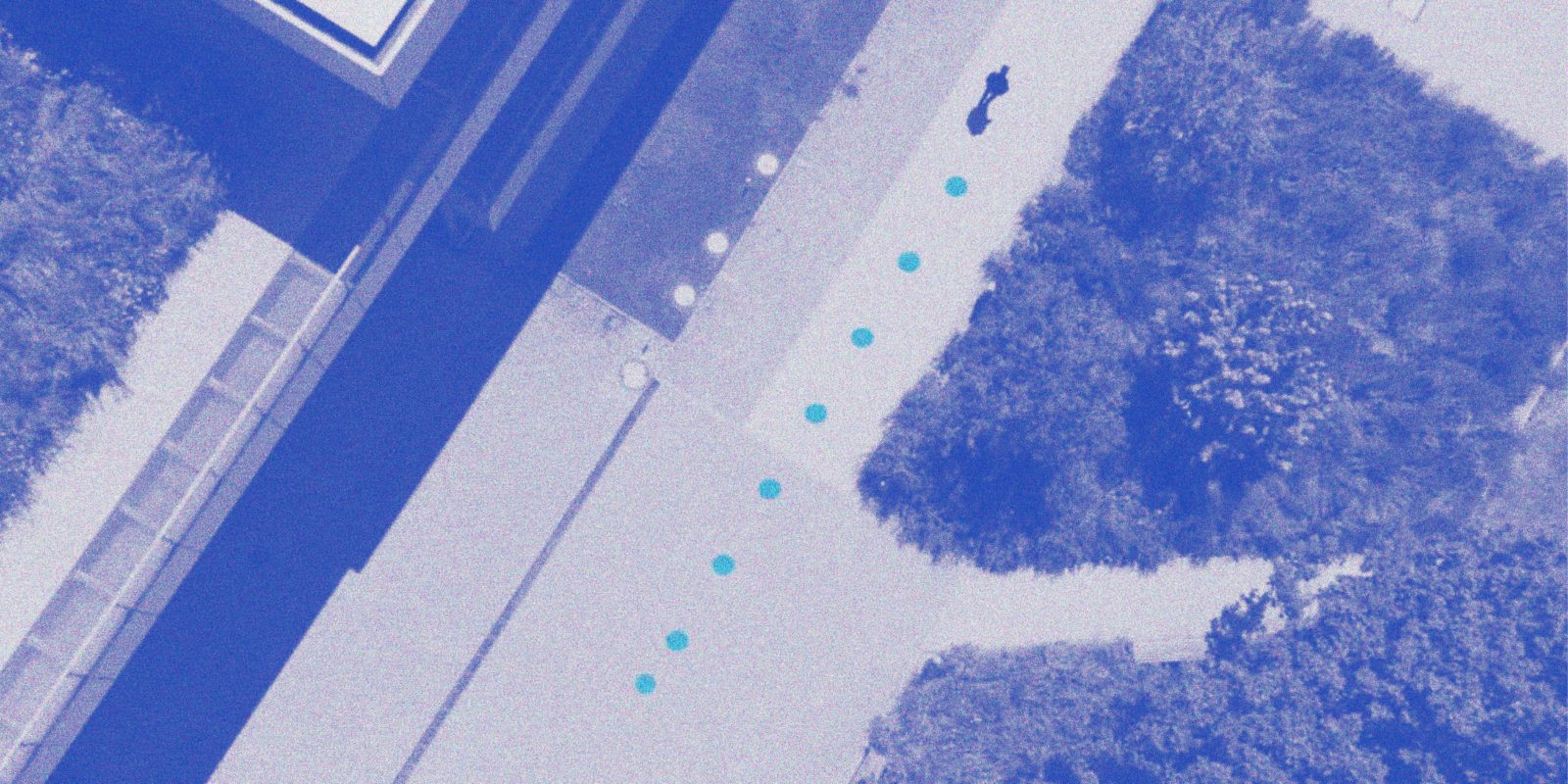

Under Surveillance. How Location Data Jeopardizes German Security.

The winner of our Innovation Award 2025 category began as a single investigation into how commercially traded location data could be used to trace security-relevant individuals in Germany. It quickly became something else: a live, expanding examination of how deeply embedded (and how poorly controlled) the location-data economy really is.

Since publication, the project has grown into an ongoing international collaboration, with partners across Europe and the United States and new datasets from countries including France and Belgium. The reporting triggered concrete responses, including a warning from the European Commission to EU institutions and member states and scrutiny by a German data protection authority of Germany’s most widely used weather app, which has since restricted its use of location data. The team also mapped how tens of thousands of popular apps feed the ad-tech ecosystem, showing why effective regulation remains structurally difficult. An extensive television documentary scheduled for release this year will take the investigation further, revealing findings that have not yet been made public.

Time has also sharpened the stakes. What initially appeared as a systemic vulnerability revealed itself as an immediate threat. As Rebecca Ciesielski puts it, “we did not fully grasp how real and immediate the threat posed by this data is for those affected.” Subsequent reporting showed that location data from the advertising ecosystem is already being used operationally, including by U.S. immigration authorities to track individuals for deportation. In its most extreme cases, the misuse of such data can determine who is located, targeted, or exposed, with consequences that can be irreversible for the people concerned.

Legal experts broadly agree that trading this kind of data is incompatible with existing data protection law, and political calls for stronger safeguards have resurfaced across party lines. At the same time, proposed reforms risk weakening core protections by narrowing how personal data is defined. The investigation shows why that distinction matters: even without names or email addresses, location data can still be used to identify, track, and harm individuals, making any dilution of protections a high-stakes gamble.

Serving Moscow

Serving Moscow did not end with the exposure of election interference around Moldova’s 2024 presidential race and EU accession referendum. Instead, it documented a system in motion that adapted as soon as it was revealed.

The initial undercover investigation showed how a Moscow-directed network bribed voters, moved money from the Russian Federation into Moldova, and coordinated political action on the ground through a rigid hierarchy of activists. What followed made clear that this structure was not dismantled so much as reconfigured. In 2025, ahead of Moldova’s parliamentary elections, the reporters uncovered a strategic shift: from physical mobilisation and cash payments to large-scale online manipulation.

This second phase emerged almost by accident. Due to an internal error within the network, journalist Natalia Zaharescu remained registered as an “activist” after publication. Days later, she was contacted again, this time with a new assignment. The proposal was no longer to attend rallies or recruit voters, but to help build a digital propaganda force. The follow-up investigation, Kremlin’s Digital Army, revealed hundreds of coordinated Facebook and TikTok accounts spreading anti-EU, pro-Russian narratives, managed from the same centre as the earlier vote-buying operation.

Over ten months, reporters infiltrated and documented this new structure. The findings sparked public debate ahead of the 2025 parliamentary elections about the role of social media in political interference. By then, the earlier, offline vote-buying network exposed in 2024 had been dismantled by Moldovan law enforcement, while criminal cases against several figures identified in the reporting remain under investigation. What the project ultimately captured was not a single operation, but an evolving playbook which adjusts its methods, but not its objectives.

Growing Up ‘Non-Western’ in Denmark’s Nanny State

This project followed how a set of policies designed to reshape “parallel societies” reaches into the most intimate spaces of family life. By focusing on compulsory day care for one-year-olds and quotas that limit how many children from targeted neighbourhoods can attend the same centres, the reporting showed how integration policy is experienced not as abstraction, but as daily coercion, negotiation, and loss of choice.

Since publication, the ground has continued to shift. Activists and residents are still contesting the so-called ghetto laws, and in December the Court of Justice of the European Union preliminarily ruled that parts of Denmark’s housing policy under these laws may violate EU anti-discrimination rules, setting up further legal battles at the national level. While that ruling did not directly address the day-care mandate examined in the story, its implications travel outward. As Gabriela Galvin notes, “this lawsuit did not cover the part of the ‘ghetto laws’ that I focused on…but the EU court ruling will have ripple effects.”

There have also been partial policy adjustments. Following sustained pressure from day-care workers, municipal staff, families, and residents, Denmark’s parliament amended the rules, allowing local authorities some discretion to relax the 30 per cent quota in specific cases, such as when both parents are working or studying. On paper, this signalled responsiveness. In practice, day-care managers say bureaucratic hurdles have blunted its impact, leaving everyday conditions in many neighbourhoods largely unchanged and reinforcing calls for the mandate and quota to be fully repealed.

What remains at stake reaches beyond Denmark. The unresolved question is how Europe reconciles its stated commitments to equality and inclusion with policies that classify, manage, and discipline communities along ethnic lines. As the reporter reflects, the European project itself is under strain, and “we should pay close attention to what the EU and individual countries are actually doing, not just what they say they stand for.”

Months on, none of these stories feel finished. They show how power adapts in real time as surveillance markets expand, election interference mutates, social policy tightens its grip on everyday life. Attention shifts quickly, but impact unfolds more slowly.

These projects frame journalism as a practice of attention: staying with a problem long enough for its shape to become clear, its mechanisms traceable, and its impact harder to dismiss.