Investigative

Reporting

Award

Ukrainian Supreme Court Judge With Russian Citizenship

published by Radio Svoboda, Ukraine

Amid heightened wartime worries about public officials’ ties to Russia, the investigations mark the highest-level government scrutiny of a judge in the Ukrainian judicial system since Moscow’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine began.

For nearly five years, Lvov, 55, has been chairman of the Supreme Court’s Commercial Court of Cassation, Ukraine’s top court for economic and property disputes, which hears cases involving major Ukrainian businesses. In that capacity, he has had access to state secrets.

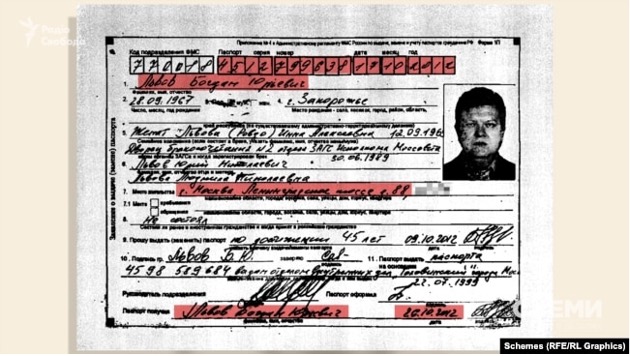

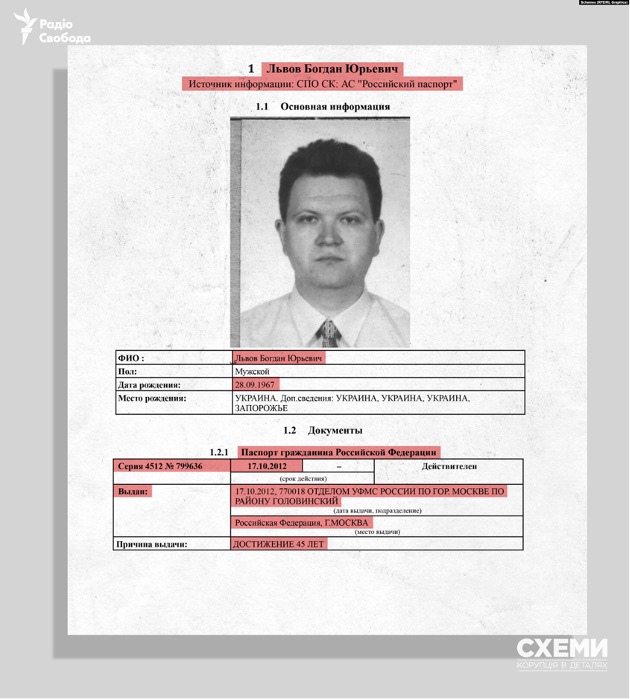

According to documents obtained by Schemes from the Russian passport registry, Russia’s Federal Tax Service, and the Russian real-estate registry, Lvov apparently also has had a Russian passport and a Russian taxpayer identification number during that chairmanship and previously was part owner of an apartment in Moscow.

Under Article 126 of the Ukrainian Constitution, judges who acquire foreign citizenship can be deprived of their powers.

Ukraine’s citizenship law also authorizes the president to revoke the citizenship of Ukrainians who willingly obtain another citizenship. Three prominent civil-society organizations — the Anti-Corruption Action Center, the DEJURE Foundation, and Automaidan — urged President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on September 16 to do so in Lvov’s case.

Ukrainian law also requires judges to provide a full annual accounting of property both they and their spouses own. Schemes acquired information from Russia’s real estate registry, Rosreyestr, that indicates Lvov was the co-owner of a Moscow apartment with his wife, Inna Lvova, until 2012, when he gave her his share. Lvova, who also has a Russian passport, still co-owns the residence with her mother. None of this information appeared in Lvov’s annual financial declarations, which are required to include information about a spouse’s possessions.

For this reason, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) has begun a criminal investigation into whether Lvov included “knowingly inaccurate information” in his annual financial declarations by failing to disclose the property registered under his and his wife’s alleged Russian passport numbers.

NABU has summoned Schemes journalists for questioning as witnesses in this investigation.

If Lvov is prosecuted and convicted, under Ukraine’s Criminal Code he would face potential penalties of a two-year sentence of restricted freedom, a sizable fine, and a ban of up to three years on holding “certain positions” and engaging in “certain activities.”

Despite the evidence, Lvov denies that he has Russian citizenship, a Russian passport, or a Russian taxpayer identification number.

On September 15, the day the Schemes report was published and posted on YouTube, he filed a complaint against the journalists of RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service with the State Bureau of Investigation (DBR).

In a copy of his complaint that he posted on Facebook, the judge alleged that the “distribution of false information,” through his “discrediting” as a public official of the judicial system is “aimed at destroying the system and directly affecting the results” of court cases “involving the Russian Federation.”

Under his chairmanship of the Commercial Court of Cassation, he asserted in a separate September 16 statement on Facebook, “more than 170 billion” hryvnya ($4.6 billion) have been collected from Russian gas exporter Gazprom; the government reclaimed real estate, land, and military facilities from commercial owners; and government cases against “oligarchic groups…were satisfied.”

“There was not a single case of favoring Russia or related companies,” Lvov said.

The State Bureau of Investigation declined a request from RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service for comment, saying that information on the matter was “restricted.”

Schemes based its investigation and findings in part on documents obtained digitally and via other means from Russia’s passport agency, Federal Tax Service, Border Guard Service, and Rosreyestr.

‘I Need To Figure It Out’

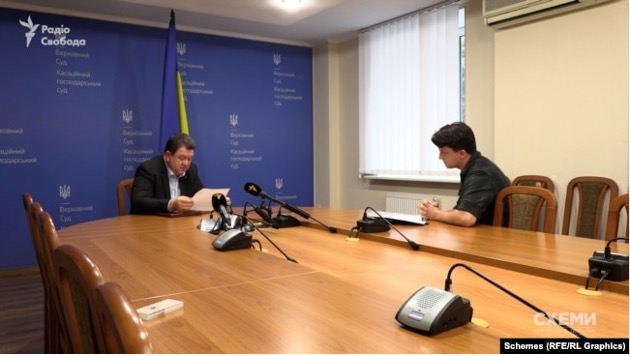

In a filmed interview on September 13, a Schemes reporter asked Lvov whether he has Russian citizenship, and he denied it twice, saying, “No.”

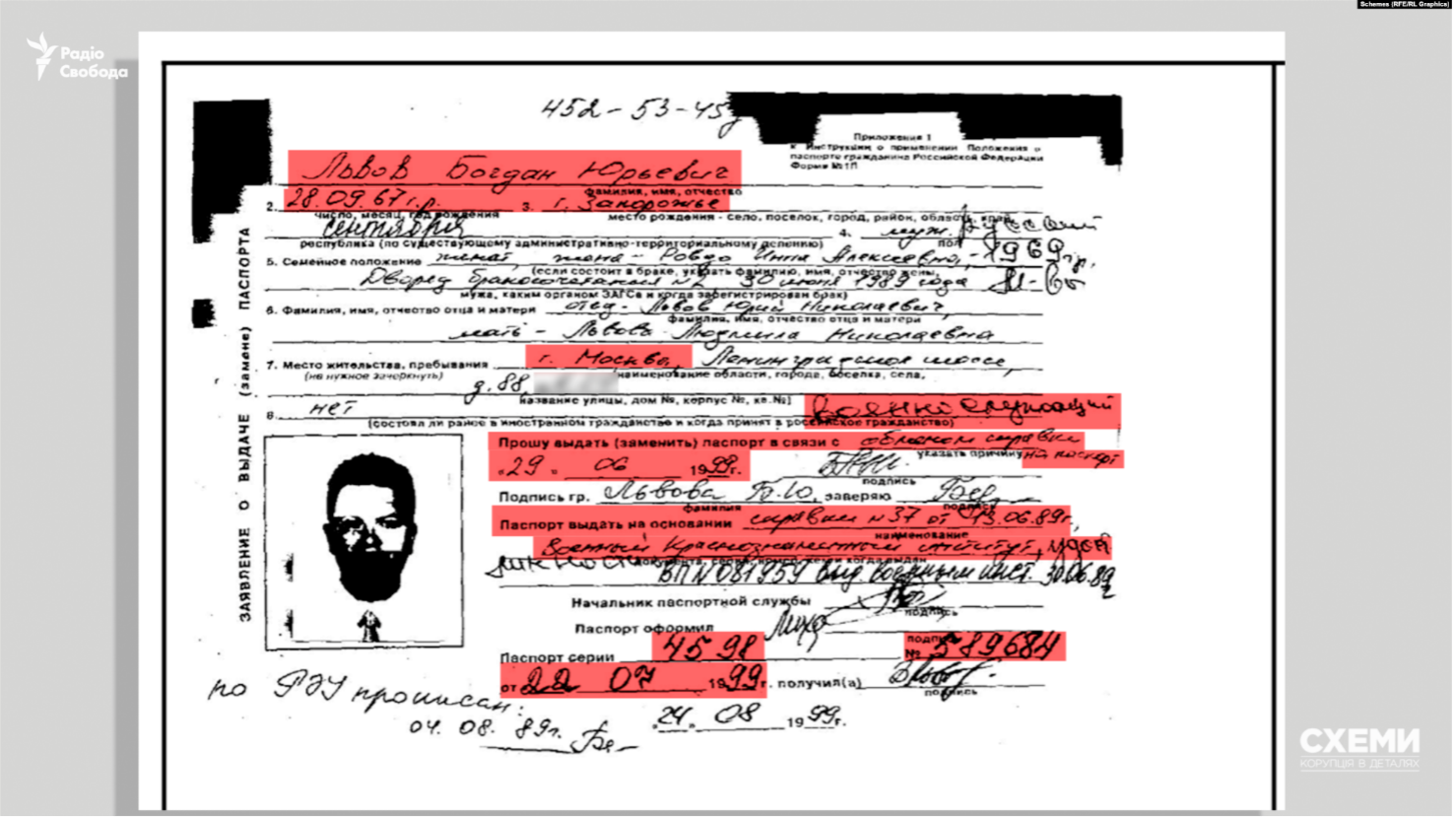

The reporter then showed Lvov copies of official documents from Russia’s passport agency and real-estate registry that indicate he applied for and received Russian citizenship and has a valid Russian passport that he used for real-estate transactions in Moscow.

Lvov said that the signature on the 1999 passport application is “similar to my handwriting in general.” Asked about the photograph of him that was attached to the application, he said he would not “guess” about its origins.

Later in the interview, Lvov suggested that the documents were an attempt to discredit him.

“Unfortunately, there are institutions for which nothing is impossible,” he said, without elaborating.

The evidence presented by Schemes came from a wide array of sources.

Schemes checked whether Lvov had actually used the passport that the Russian government has registered in his name. As of September 27, the Russian Interior Ministry did not list Lvov’s passport as invalid.

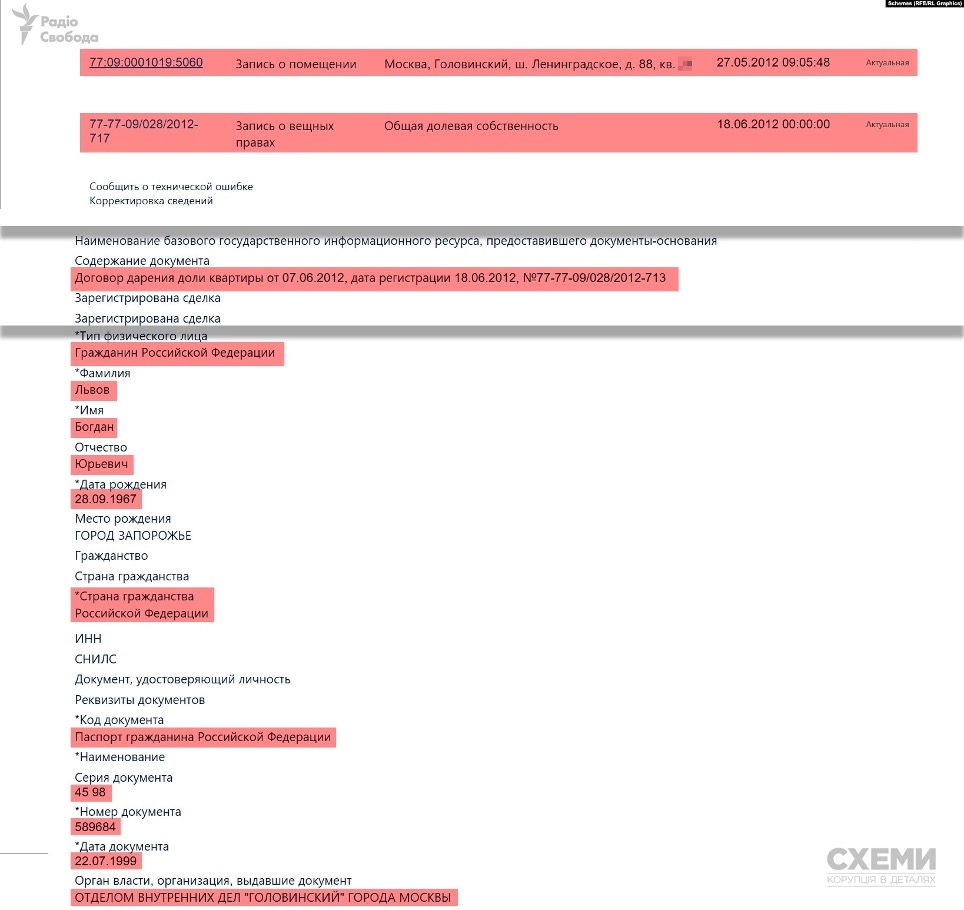

Documents from Rosreyestr indicate that his passport number was used to register a two-room apartment at 88 Leningradskoye Shosse in Moscow that Lvov co-owned with his wife, a native Russian citizen, and his mother-in-law.

Based on recent ads for the sale of other apartments in the building, the residence has an approximate market value of roughly 18 million rubles ($310,000).

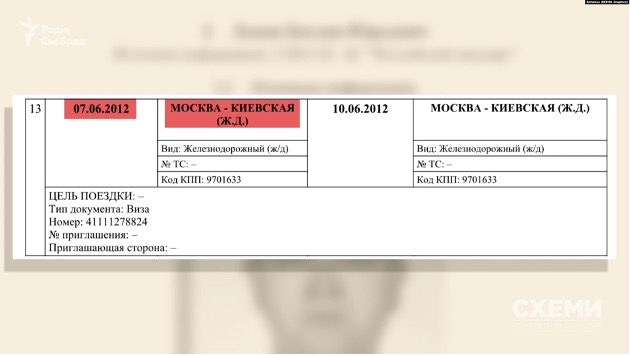

According to a gift agreement contained in the Russian real-estate registry, Lvov transferred his 25 percent share in the apartment to his wife on June 7, 2012. Records obtained from the Russian Border Guard Service database demonstrate that Lvov traveled to Moscow from Ukraine by train on that date.

In the filmed interview with Schemes, Lvov stated that he did not recall “all this,” referring to the Russian registry’s details about the Moscow apartment. He identified the residence as his mother-in-law’s address.

He said the information Schemes laid out about the apartment “needs to be checked a little more,” adding: “I remember what I didn’t do 100 percent, but when it doesn’t match the documents you have, then I need to figure it out.”

At the interview, Schemes left copies of the documents with Lvov at his request. He did not respond to a request to substantiate his denials of Russian citizenship before the Schemes report was published on September 15.

Aside from the DBR, Lvov also has petitioned the SBU to open a criminal investigation under Article 109 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code, which addresses attempts to seize power, including by violence. He did not specify potential targets for this proposed investigation.

In later statements, also posted on his Facebook page, he has contended that the 2012 Russian passport application form that Schemes reported he had submitted to renew his Russian passport did not enter into use until 2013.

He further alleged that Schemes cut off a part of the image for this application that suggested it was for the renewal of a passport issued in 1998, rather than the renewal of the passport Schemes reported he received in 1999.

“[S]uch attacks on judges, using media and fake facts, are not just unacceptable, but threaten the independence of the entire judicial branch as a whole,” he wrote on September 26. “Someone decided they could put pressure on judges with the help of journalists. It’s not going to be like this.”

Lvov pledged to “appeal” this matter “on behalf of President Volodymyr Zelenskiy” and bring it to the attention of “representatives of Western democratic institutions” and U.S. “congressmen.”

Zelenskiy’s office has not commented publicly about the Schemes investigation.

Schemes Response

In a September 29 follow-up article, Schemes published instructions for readers to check its reported details about Lvov’s passport in a Russian Interior Ministry online database of invalid passports.

Both sources show that the number that appears in Russian passport bearing Lvov’s signature and name remains valid. The image from the Russian Federal Tax Service provides the judge’s tax identification number.

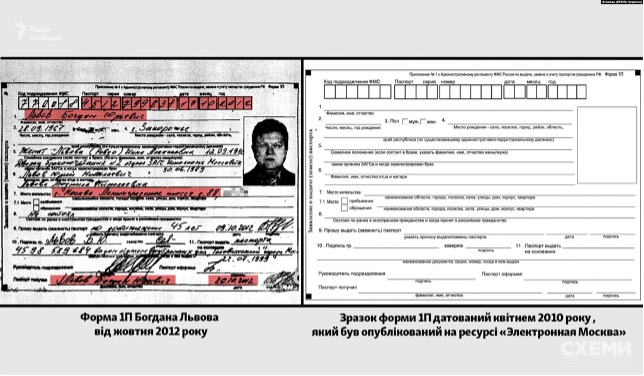

In response to Lvov’s allegation concerning the 2012 passport application that bears his signature, Schemes has traced the application that featured in its investigation to the official application forms in use in Russia as of 2009. An April 2010 sample form on Elektronnaya Moskva, where the city of Moscow publishes official forms and regulations, fully corresponds to the one published by Schemes. It would have been in active circulation in October 2012, the month that Lvov’s passport renewal form was submitted.

The Russian site Pasportist, which publishes samples of the document necessary to receive a Russian passport, contains a document for May 2012 that also fully corresponds to the passport application obtained by Schemes.

While the Russian passport registry automatically generated a form that suggests Lvov’s passport application was first submitted in 1998, rather than in 1999, as Schemes reported, the photo beneath the 2012 passport application that the registry attributes to Lvov shows a written passport application with his signature from 1999.

Moreover, Russian government databases including the real-estate registry respond to the passport number included in the passport applications under Lvov’s name.

Schemes provided evidence that Lvov previously used his Russian passport number not only to register his co-ownership of a Moscow apartment but to transfer that ownership to his wife. This information exists not only in Rosreyestr but also in older databases that were “merged” and that no longer accept new data entries.

Schemes requested an assessment from another investigative journalist accustomed to working with Russian official forms, Christo Grozev, the lead Russia investigator at Bellingcat.

Grozev said that he has found “several Russian passports” bearing Lvov’s name in Russian databases that date back “long before your investigation.”

“So I rule out the possibility that he either was granted Russian citizenship recently or that he did not know about it…. His passport is not listed as canceled in the public database of invalid passports. So, for me, these two verification methods prove that he has a valid passport from the Russian Federation,” Grozev said.

Bellingcat is not the only entity reviewing the evidence.

Security Service Assessment

Prior to the September 15 publication, the SBU informed Schemes that it “has information that may indicate that Judge Bohdan Lvov has Russian citizenship,” but was “working on obtaining materials that could finally confirm or refute the available data and, in particular, can serve as relevant legal evidence” of Lvov’s alleged Russian citizenship.

According to information Schemes has received from multiple sources, the SBU has now confirmed the judge’s Russian citizenship to several state bodies, including the State Migration Service and Zelenskiy’s office.

The SBU has not commented publicly on the reported confirmation.

A representative of the SBU press office earlier told RFE/RL that, in addition to the State Bureau of Investigation, which addresses alleged crimes committed by judges, the agency also was looking into the Schemes findings.

“The position of the Security Service remains unchanged — representatives of the judicial branch of government must possess Ukrainian citizenship only,” the SBU representative stated.

Judges And Justice

Concern about the loyalties of Ukrainian judges has heightened since Russia launched a large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February, dramatically expanding a localized conflict in the east into a full-blown war that has now killed tens of thousands of people.

Russia, which seized Crimea in 2014, staged so-called referendums this month in four Ukrainian regions it partially occupies and used the processes, which Kyiv and the West have dismissed as a sham and which are illegal under international law, to claim a large portion of Ukraine as its own.

In an interview with RFE/RL in May, Andriy Smyrnov, deputy head of Zelenskiy’s office, spoke of unnamed judges who he said “really betray the interests of both the judiciary and the state” and act as “’quiet’ collaborators.”

On September 15, the SBU reported that it had informed an unnamed judge on the Northern Court of Appeal about its suspicions and about evidence that the justice had “justified the atrocities of the occupiers” and “incited acquaintances to cooperate with the enemy,” while speaking “disparagingly” about the Ukrainian armed forces. The former two actions rank as criminal offenses.

No such criminal charges have been brought against Lvov.

Ukrainian Supreme Court Chairman Vsevolod Knyazyev told RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service that the Schemes investigation was the first he had heard of Lvov’s alleged Russian citizenship. In his 2017 application to join the Supreme Court, Lvov had stated that he did not hold citizenship of any other state.

On September 16, after receiving notification from the SBU that it had suspended Lvov’s access to state secrets, the Supreme Court, citing investigations into the information disclosed about Lvov’s alleged Russian citizenship, did the same.

If Lvov’s Russian citizenship is confirmed “in the manner established by law,” Knyazyev said, the 21-member Higher Council of Justice, the only state body that can dismiss or appoint a judge, must take “the relevant decision.”

The Supreme Court is currently fulfilling the Higher Council of Justice’s role since the council’s membership is incomplete.

(If the report is confirmed, says Roman Maselko, a newly appointed member of the Higher Council of Justice, Lvov “should lose his status.”)

One newly appointed member of the Higher Council of Justice, Roman Maselko, emphasized that if “official confirmation” of Lvov’s Russian citizenship is issued, “the judge should lose his status.”

Whether the Supreme Court or the Higher Council of Justice will address Lvov’s case is unclear.

A separate procedure exists for Lvov’s status as the appointed head of the Supreme Court’s Commercial Court of Cassation. The court’s 44 judges would have to agree by a secret, majority vote to remove him from office.

At a September 19 session, presided over by Lvov, the justices did not agree to hold a vote of confidence in Lvov or to suspend the automatic scheduling of cases he will hear, according to the court’s press service.

One of the court’s judges, Olena Kibenko, posted on her Facebook page that 13 of the court’s judges had supported an initiative to discuss the prospect of Lvov’s “early termination” on September 26, but the number was insufficient for a special session of the judges to occur. A separate but similar initiative is under way, she said.

However, Commercial Court of Cassation Judge Ivan Mishchenko said on September 30 that judges on the court had gathered enough votes to hold a special session and consider a no-confidence measure. The Supreme Court announced that the session, to consider Lvov’s possible dismissal from his post as chairman, would be held on October 3.

Fellow judges do not claim that Lvov is a Russian citizen or has real estate in Russia, Kibenko said earlier in September: “But such allegations, supported by documents, are too serious and cannot be ignored.”

For now, Lvov is still hearing cases; most recently, on September 27, according to the Commercial Court of Cassation’s schedule.

English version written by Elizabeth Owen based on reporting by Heorhiy Shabayev and Natalie Sedletska.