Investigative

Reporting

Award

Roland Berger’s self-deception: The star consultant, his Nazi father and the guilt of German industry

published by Handelsblatt, Germany

Photo: Mona Eing & Michael Meissner / José Giribás [M] Düsseldorf, Munich, Vienna

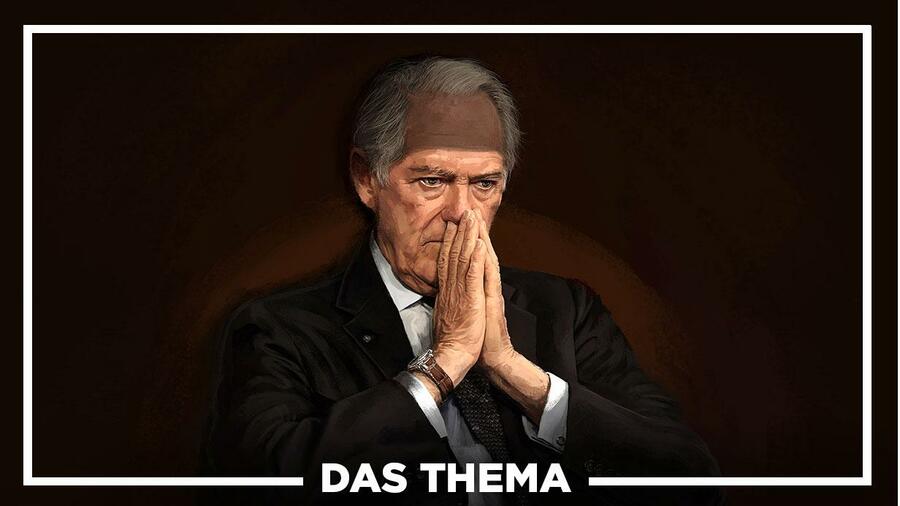

It is a prize that is particularly dear to Roland Berger: The foundation of the most prominent German management consultant has awarded one million euros for extraordinary services to the protection of human dignity. Since 2008, Roland Berger has also used the award to commemorate the man he always called his moral role model: Georg Berger, his father.

When Berger calls, everyone comes. The now 81-year-old has left his mark on the German economy and has a top-class network. Patrons of the Roland Berger Prize have been German Presidents Christian Wulff and Horst Köhler. The jury was composed of former Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer, former President of the European Commission Romano Prodi and Nobel Peace Prize winner Kofi Annan. When the eighth Roland Berger Human Dignity Award is presented next Monday in Berlin, the keynote speaker will be Wolfgang Schäuble, President of the German Bundestag.

So many friends, and much honour – especially when you consider one thing: Berger’s father was not the upright Nazi victim his son made him out to be in numerous interviews. On the contrary: Berger senior was a profiteer of the Hitler regime.

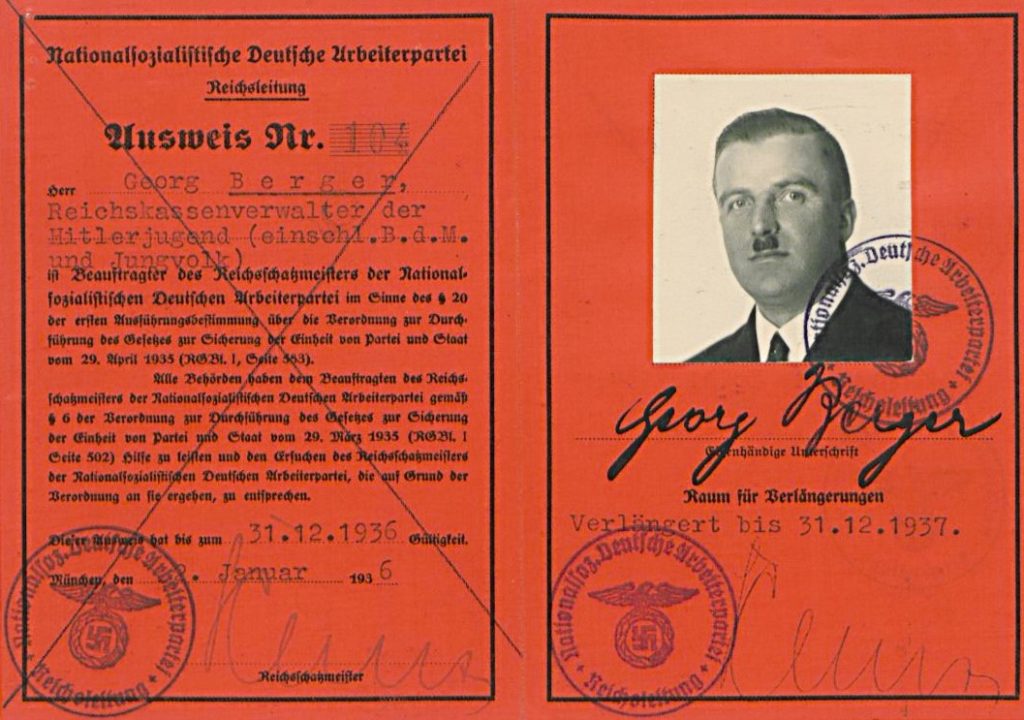

For 13 years, Georg Berger was a member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP). He worked as chief financial officer of the Hitler Youth, was appointed Ministerial Councillor by Adolf Hitler in 1937, later headed an “Aryanised” company in Vienna as General Director and lived in a villa confiscated from its Jewish owners.

Handelsblatt researched these details in months of work. Faced with the results, Berger did not deny them. He engaged the well-known historian Michael Wolffsohn, an expert on German-Jewish history. A few days ago, they spoke about the true face of Georg Berger together for the first time. The bitter conclusion of his son: “If you will: Yes, then it must have been an unintentional ‘tragic self-deception’ that I was guilty of” (see interview).

Director of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Michael Blumenthal (left), with Roland Berger

Photo: ddp

German history remains complex – and the process of coming to terms with it still has many facets, even in 2019. It is only five months ago that „cookie heiress“ Verena Bahlsen caused outrage with her words on the Nazi history of her family business. “Bahlsen did nothing wrong,” said the great-granddaughter of the founder, Hermann Bahlsen, although the company employed more than 200 forced laborers during the Nazi era. Shortly afterwards, she apologized. Now an independent historian is to examine the topic – as other companies such as Dr. Oetker have already done (see box “Dark Foreboding”).

Verena Bahlsen was 26 years old when she presumed to make her statement about the German past once. Roland Berger is 81 and has been telling people for almost two decades that his father was a victim of the Nazis.

He could have known better. The contradictions in his father’s life seem too obvious. This raises the basic question: Was it a case of tragic self-deception or a deliberate historical misrepresentation?

Dealing with the past is a difficult topic in Germany. The NSDAP once had more than seven million members. The children of the Nazis rarely spoke about crime and guilt. “The ambivalence between the love for the parents and the awareness that the parents have done wrong is a tensile test for the children,” explains sociologist Uta Rüchel. “An embellishment of a reality so different is not an isolated incident.”

This also applies to those to whom others look up. For decades, Roland Berger was the number one in his industry. He has counselled business leaders and governments, taught at universities and received numerous national and international awards (see box “Doyen of the consulting industry”). Nothing that Georg Berger may have ever done diminishes his son’s life achievement. But whatever drove Roland Berger to publicly transfigure his father, naivety would be a strange response from an otherwise well-versed judge of character.

Chief Financial Officer of the Hitler Youth

Roland Berger’s first public statements about his father date from March 2003, when he told the Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel that his father was a member of the NSDAP but had “left the party due to religious conviction” before the war began. In the course of time, Berger dramatized the role of his father, who died in 1977, more and more. In 2012 he praised him in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung: “Even though it meant mortal danger for himself, he demonstrated: Not with me.”

It was a moving story that Berger told. But it’s not true. Handelsblatt has evaluated historical newspaper articles, combed through numerous archives and studied Georg Berger’s personnel and criminal records. He was not the man his son described.

Georg Berger was born in Würzburg on 12 September 1893. He learned the merchant’s profession and in January 1911 became a stock accountant in Kulmbach. Berger fought in World War I where his arm was wounded. After the end of the war, he worked freelance for various companies, becoming director of the Tiroler Industriewerke in November 1922; from 1927 to 1934 he was an independent tax consultant and trustee. Afterwards, he dedicated his labor entirely to the National Socialist German Labour Party.

Georg Berger was a member of the NSDAP from 1931 to 1944

Photo: Archive

All of this can be seen from the personnel questionnaire of the NSDAP administration dated 22 September 1935, signed by Georg Berger himself. His son later said that Berger had joined the NSDAP in 1933 on the advice of Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht. “He probably also believed that the party could do something positive,” Berger junior told the Rotary Magazin, and continues the quotation: “After the ‚Night of Broken Glass‘ 1938 it became clear to him where the whole thing would lead, namely to the Holocaust. Consistent as he was, he therefore quickly left Hitler’s party.”

That’s not true. Georg Berger had joined the NSDAP two years earlier – on 1 June 1931 – and paid his membership fees until September 1944, when he became an auditor in the NSDAP administration in April 1934. On February 24, 1935, in the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich, he took his oath to the Führer: “I swear: I will be loyal and obedient to the Führer of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, I will observe the laws and conscientiously fulfill my official duties, so help me God.

On January 10, 1936, Berger was promoted to Reich Treasury Administrator for the Hitler Youth. In November 1937, when his son Roland was born, the father was the chief financial officer of the Nazi junior staff and also liaison officer to the top authorities. Berger carried a service pistol, a Walther PPK, caliber 7.65. He immortalized his attitude in the foreword of the book “Verwaltungs- Dienstvorschriften für NSDAP-Hitler-Jugend” („Administrative Manual for NSDAP Hitler Youth“). When Berger resigned from his posts on 30 September 1939, he said this was due to health reasons. He requested a letter of thanks from Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess – and got it.

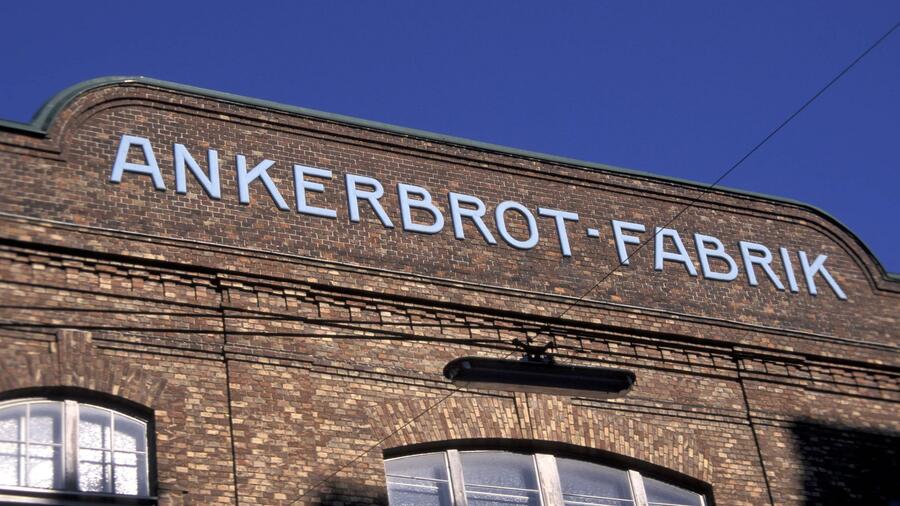

Director of an “Aryanized” factory

Ankerbrot factory

Photo: imago stock&people

Handelsblatt asked Roland Berger for an interview a month ago. What made him think that in 1938, his father tangled with the Hitler regime risking his life, when actually, Georg Berger was and remained a top functionary of the NSDAP?

On 11 October, the management consultant invited to his office in the noble Maximilianstraße in Munich. At his side: Michael Wolffsohn. Together with the Historical Institute of the University of Potsdam, the Jewish historian is to examine the role of Berger’s father during the Nazi era. One thing was already clear, Wolffsohn said in the interview: “Georg Berger was indeed a profiteer of the NS system.“

On this afternoon in Munich, Roland Berger explained that he had so far believed the opposite – the victim story: “It all seemed plausible to me,” said Berger. “In that respect, there was no doubt in my mind.“

In fact, the image of his father became more and more favorable over the years. In November 2008, he took his idealization to a new level: The Roland Berger Foundation was created. Equipped with 50 million Euros in capital from Berger’s private assets, it was to work for a fairer distribution of opportunities in society. In addition, his foundation also awarded the Roland Berger Human Dignity Award. “This goes back to my father, a convinced Christian,” Berger later explained to the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Berger’s good deeds did not go unnoticed. On 15 November 2008, the Jewish Museum in Berlin awarded him the Prize for Understanding and Tolerance. The jury, headed by Museum Director Michael Blumenthal, postulated: “Roland Berger’s commitment to human rights and education is also based on his family’s experience under the National Socialist regime. His father had publicly distanced himself from the NSDAP and was arrested in 1944.”

In November 2008 Manager Magazin dedicated a cover story to Berger

Photo: Manager Magazin

Berger’s conscious or unconscious lie thus received a moral seal that no one questioned anymore. All the German media, including Handelsblatt, believed the heroic stories of his father as a shining light in dark times. One magazine from Hamburg was particularly trusting.

“Exclusively for Manager Magazin, the First Counsellor of the Republic has opened his private archive and took stock of his life in a number of conversations,” wrote the editorial staff in its cover story in November 2008. As a child, Berger “experienced how degradingly his father was treated in the Third Reich.“

His father was supposedly defiant. The deep believer would have steadfastly refused to resign from the church against the Nazis’ urging. Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach would had even forbidden Roland Berger to be baptized. His parents wouldn’t have stuck to it. Georg Berger had refused to finance anti-religious events as a money manager. “In order to change his mind, he was offered the post of a ministerial councilor,” the article said. Yet Hitler had already appointed Georg Berger as a ministerial councilor on April 20, 1937 – seven months before Roland Berger’s birth.

“To this day my father is a moral role model for me. He stands for decency and courage.”

– Roland Berger in Focus, July 9, 2012

There were many of these contradictions when Berger spoke about his father. No one asked. In the Hamburg narrative of Georg Berger’s life story, he went his way upright under the totalitarian regime. “Berger renounced the supposed career and switched back to the free economy in May 1939,” wrote the Manager Magazin. And continued: “He rose to the position of General Director of the Ankerbrot-Werke, the largest bread bakery in Austria. … Berger had been assigned a classic task of financial rehabilitation. He was to deleverage the company, minimize losses and adjust the ownership”.

Free enterprise? Classic task of financial rehabilitation? Ankerbrot was founded in 1891 by the Jewish brothers Heinrich and Fritz Mendl. In 1938, the Reich Commissioner for the Treatment of Hostile Assets confiscated their company, the Mendl family fled to Switzerland, later to the USA and New Zealand. Thus “Aryanised”, the large bakery was put into public sequestration.

The fact that Georg Berger was able to become general manager of Ankerbrot was systemic. “Leading cadres of the Hitler Youth received preferential treatment in Nazi Germany,” explains NS historian Michael Buddrus. Details were regulated by an order of Hitler’s deputy Heß. Those Hitler Youth leaders who wanted to take up a different profession were “to be supported by all party departments in their efforts to obtain an appropriate position”.

A splendid villa in Vienna

Villa Sternwartestrasse 75 in Vienna

Roland Berger spent his early childhood in the villa confiscated from Jews

Photo: Archive

And Berger senior was supported. The newly appointed boss moved from Berlin to Vienna and stayed in the Hotel Erzherzog Rainer for ten months. Then, the Nazis made a villa available to him.

The property at Sternwartestraße 75 still adorns Vienna today. It is located in the Cottage Quarter, designed at the beginning of the 19th century as a residence for civil servants, teachers and officers. Later, artists settled here, two houses further lived the writer Arthur Schnitzler until 1931. Behind the opulent villa, into which the Berger family moved shortly before Christmas 1941, there was a pond in the large garden, Roland Berger later told journalists. Here, in winter, he learned how to skate as a little kid.

The Bergers had plenty of room. A floor plan of the villa shows two living rooms, a dining room, a ladies’ room, a gentlemen’s room, two children’s rooms and a children’s playroom. In the attic, there were two rooms for servants, one for guests, one for ironing and a room for reflection.

The rightful owners of the estate were Heinrich and Laura Kerr. On November 10, 1938, Gestapo officials took all cash from the then 74 and 76 year old Jewish couple, their insurance policies, necklaces, watches, even cuff links and tie pins. Later, the Nazis also confiscated their villa. The Kerrs were expatriated – like many Jews from this neighborhood.

As a rule, high-ranking National Socialists moved into their houses. Sternwartestraße 75 was added to the “Aryanised” company Ankerbrot, and the villa was used as a “company flat” for its general director from then on. Georg Berger had his Supervisory Board grant him a right of preemption. The Kerrs’ housekeeper was allowed to stay; she was of Aryan descent.

Roland Berger never mentioned any of this when talking about his father. He talked a lot, though. “To this day, my father is a moral role model for me. He stands for decency and courage,” Berger told the German magazine Focus in July 2012 and told Rotary Magazine in August 2015, “If my father did something, he was convinced of it. He was a serious believer.”

Alfred Proksch

In 1941, the SA-Obergruppenführer introduced Berger as the new head of the large Ankerbrot bread factory

Photo: ullstein bild – Erich Engel

In spring 1941, Ankerbrot organized a “social evening” in the Sofiensäle, a very popular event location in Vienna. It was a symbolic place. In May 1926, the NSDAP in Austria was founded there, and from 1938, the Sofiensäle were a collection point for Jews who were to be deported. It was precisely here that SA-Obergruppenführer Alfred Proksch introduced Berger to the company and Vienna’s society.

Proksch was a Nazi of the first hour. He had helped build up the NSDAP in Austria and even lost his citizenship due to his ardent admiration for Hitler. When the NSDAP was banned in Austria in 1933, Proksch fled to Germany. In 1938, he returned to his home country, which had meanwhile been occupied by Hitler’s troops, and became a group leader of the Sturmabteilung (SA).

On 15 March 1941, Proksch appeared before the Ankerbrot staff in the Sofiensäle. He was now the bearer of the NSDAP’s Golden Badge of Honour and President of the Vienna Regional Labour Office. When this man introduced a new boss, each of the 2000 employees present knew how to assess Georg Berger.

Living it up

Almost a year later, Berger came back to the Sofiensäle. On 2 February 1942, the Neue Wiener Tagblatt reported on a “Social Evening of the Ankerbrotfabrik” which had taken place there the Saturday before. There was a ballet performance, artistic cyclists demonstrated their skills. “The brilliant performances of two music bands also contributed to the fact that from the very beginning there was a brilliant atmosphere among those present”, the newspaper wrote. Berger spoke the words of welcome. The motto of the evening: “The home front greets the field front”.

In his son’s memory, this Nazi idyll did not take place – on the contrary. After his father had left the NSDAP after the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938, Roland Berger told the Süddeutsche Zeitung that “we had the Gestapo in the house every six to eight weeks. The Gestapo came even after we had moved to Vienna in 1941 … They searched everything, right down to the coal cellar, to find something against my father. It turned ridiculous. A farmer’s wife from Egglkofen, my mother’s home village, once sent us pickled eggs. They used it as an excuse to arrest my father for the first time in 1942.”

Was it? Handelsblatt has a copy of the 1943 file of the Chief Prosecutor at the People‘s Court of Vienna. In the spring of the previous year, there were several charges against Georg Berger, one of which came from the sales manager of Ankerbrot. He had been called up for military service and complained that the general director who had stayed at home was living it up in his “Jewish villa” while food and clothing were rationed everywhere.

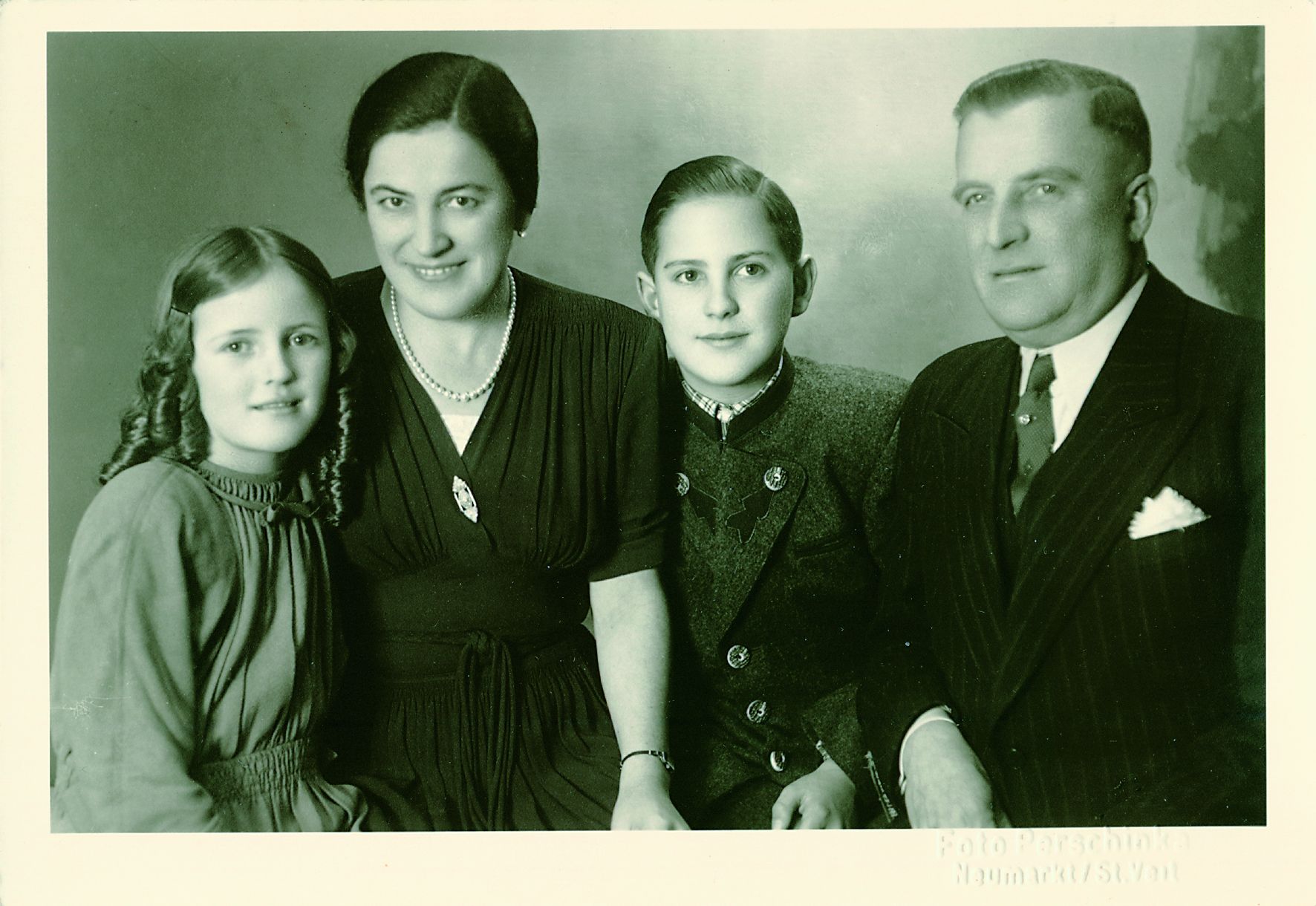

Berger family after the war

Sister Renate, mother Thilde, Roland Berger and his father Georg

Photo: Roland Berger Foundation

Confirmation

Roland Berger with his father. The recording dates from about 1952.

Photo: Roland Berger Foundation

Details are described in a police report of 20 June 1942, which states that Berger had expanded his villa “with an outrageous amount of effort, in stark contrast to the austerity measures necessitated by the war situation”. 22 of his employees spent 3,724 working hours in the middle of the war to beautify Berger’s magnificent building. Admittedly, the plant manager of Ankerbrot warned that this went at the expense of the company. However, he had “not been able to achieve the withdrawal of the workers from the adaptation work”.

The officials estimated the cost of the reconstruction at 80,000 Reichsmark. This would correspond to a current purchasing power of more than 300,000 Euros. According to documents, Berger paid one tenth of the sum, the company paid the rest. In fact, the project would have required a permit from the Labour Office and the municipal administration, the police officers criticised. Berger had circumvented the regulation by declaring the reconstruction as “minor”. In the report this was recorded as “deliberate deception”.

The Nazi officials classified Berger’s activities as war economy crimes and initiated proceedings. Berger had damaged the reputation of the NSDAP through his conduct as a manager. According to the investigations, almost every day an employee brought “three to four kilos of fine baked goods” into the house, without Berger handing over the food stamps provided. Berger is also said to have burned 3,850 kilograms of heating material, which “was only intended for the vital operation of the company”.

On April 3, 1942, the Gestapo confiscated 68 eggs, a pot containing ten kilograms of tallow, seven and a half sticks of clarified butter and four and a half kilograms of chocolate from Berger’s villa. Food hoarding was punishable by law. On June 16, 1942, the Gestapo arrived again and, according to the protocol, found 18 bottles stored in a wine rack that were filled with clarified butter, 30 kilograms of sugar cubes, 45 bottles of fruit juices, 50 kilograms of bee honey and more than 300 bottles of sparkling wine and wine. In addition, Berger had stored 130 packages of washing powder, eight kilos of curd soap, as well as furniture and clothing fabric in large quantities in his villa.

Berger later testified that he had acquired the food and textiles shortly before the war. Berger’s wife, Thilde, on the other hand, explained during her questioning that she had received the clarified butter from relatives in 1941 – two years after the war began.

The NS officials not only classified Berger as a thief, but also as a fraud. After the first search, he decanted the clarified butter into wine bottles to deceive the police. In July 1942, Berger had to leave the board of Ankerbrot AG. Nevertheless, he did not leave his official residence.

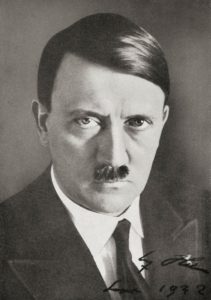

Adolf Hitler

The dictator appointed Georg Berger as a ministerial councilor on April 20, 1937

Photo: imago images / Design Pics

Roland Berger’s father now actually became a resistance fighter. For 24 months he defended his magnificent building with 600 square meters of ornamental garden against the Nazis. Information about his fight is provided by the Vienna State Archives.

According to the documents kept there, the dream property in Sternwartestraße was much sought after among Nazi leaders. Berger had made an early move, in 1942 Alfred Proksch wanted to have it. As soon as Berger was dismissed at Ankerbrot, the Gauleiter contacted the administration in Vienna. He intended to use the luxury villa as a company flat, Proksch wrote. The problem: Berger was still living there.

He had negotiated well. He paid 305 Reichsmark to the administrator of the villa every month. However, this ridiculous price hardly covered the property tax and operating costs. While the General Prosecutor reported an urgent suspicion against Berger for war economy crimes to the Vienna Regional Court, Georg Berger referred to his rental contract: it did not provide for a termination.

Under totalitarian rule, Berger fought the Nazis over contract clauses. Since he wanted to buy the villa in 1941, a possible end of the tenancy remained unregulated. The correspondence shows how Berger outmaneuvered the Nazi authorities: The president of the State Labor Office wrote in a note on February 16, 1943 that he would probably have to be provided with a replacement apartment. But either none was found, or Berger did not like them. One year later, the former General Director still lived at Sternwartestraße 75 and Proksch complained to the State Council that he “could not imagine that a rather simple transfer of a Reich-owned building” would be so difficult.

In May 1944, the villa became the property of the Reich Ministry of Labor. However, even when a representative of the Gauarbeitsamts (regional labour office) came by on 13 June 1944 for an inspection appointment, Berger held the fort. Only later that year, the Nazis put him on the street. The outcome of his trial for war crimes is unclear. He was apparently expelled from the NSDAP only in the second half of 1944.

A „minor offender“

Jewish Museum in Berlin

Europe’s largest Jewish museum awarded Roland Berger a prize for understanding and tolerance in 2008. In 2013, the museum, in turn, received the Roland Berger Human Dignity Award

Photo: Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Roland Berger summed up his father’s descent quite differently: “Political persecution and war changed my father a lot. Before that he had been a wealthy, respected entrepreneur … He was arrested for conspiracy against the NSDAP for the first time in 1942, finally in 1944. He was sent to the Eastern Front in 1945, where he became a Russian prisoner of war.” Berger also told some media that his father had been sent to the Dachau concentration camp before the last war mission.

Handelsblatt has asked all registries that could confirm this. The Dachau concentration camp memorial site has no entry for Georg Berger. The International Center on Nazi Persecution in Bad Arolsen, whose file contains 50 million references to 17.5 million persons persecuted during the Nazi era, did not find a single card on his person. The same applies to the Federal Archives Berlin Lichterfelde, the Military Archives Berlin, the State Archives Amberg, the Bavarian Main State Archives, the State Archives Munich, the State Archives Würzburg, the Vienna City and State Archives and the Austrian State Archives. Nowhere are there any documents that identify Georg Berger as an inmate in Dachau, a Nazi victim of justice or a prisoner of war of the Soviet Union.

Berger only had to answer for his deeds and functions later. On 21 July 1947, the Spruchkammer (the German civilian court handling denazification) of the internment camp in Regensburg condemned him as a “minor offender” during the Nazi era. Berger received a fine of 500 Reichsmark and two years suspended prison sentence. During this phase he was not allowed to run a business, work independently or be a teacher, preacher, editor, writer or radio commentator.

Berger had undergone a denazification procedure – as had millions of other Germans. 95 percent of all those examined were thereby exonerated of any blame, classified as “followers” or remained unpunished for other reasons. Only 0.05 per cent were subsequently considered to be the “major offenders”. 0.63 per cent were “offenders”. 4.1 percent of those examined ended up in Berger’s category of “minor offenders”.

Historians later regarded this attempt by the allied victorious powers to come to terms with the past as problematic. “There was a lot of lying during the denazification process. Often relatives, friends or people who were dependent on the accused helped and issued them with a „Persilschein“ (denazification certificate),” explains Nazi researcher Helmut Rönz. “It is difficult to rely on the classification as a minor offender.”

“He joined the party early and served it in important positions. Therefore, he supported the NSDAP considerably through his activities.”

– Regensburg Court of Appeals decision in the denazification proceedings of Georg Berger, July 21, 1947

Georg Berger’s denazification file seems to confirm this. Given his accumulation of functions and rank in the NSDAP, he was to be classified as a major offender, the judges noted. However, numerous witnesses had testified in his defense. According to the report, Berger had been a ministerial councilor “only on paper” and had later “immediately taken up the fight against the corruption practiced by the party” at the Ankerbrot factory. In addition, he had “turned against the Aryanization of the company by the party and Gestapo”.

Evidence of this is missing in the file. While no other archive finds documents on Berger’s alleged resistance against the Nazis, his conviction or his captivity as a prisoner of war, the judges of the Spruchkammer in Regensburg apparently simply believed him. From the judgement: “The Chamber came to the conclusion that the person concerned resisted to the extent of his strength and suffered damage as a result”.

Opportunism and a career in the NSDAP did not lead to a prison sentence. Berger, however, also felt that the classification as a minor offender was still too harsh. He appealed. The Court of Cassation in the Bavarian State Ministry for Special Tasks then accepted his “political persecution of 1944”, but on 22 July 1948 it confirmed the assessment of the first instance: Berger had “substantially supported the NSDAP through his activities”.

Sales representatives after the war

Georg Berger did not want to accept the verdict. His father’s sense of justice was forever disturbed after denazification, his son told Manager Magazin in 2008. He told the Süddeutsche Zeitung just last year: “All this was very difficult for him – also the fact that he was imprisoned by the Americans in Dachau of all places.”

Georg Berger was never in Dachau. His internment camp was located 120 kilometers to the north – in Regensburg. The living conditions there were undoubtedly hard. A comparison of the calorie values of the camp rations with those of the food rations in the American occupation zone shows, however, that the inmates were in some cases better provided for than the civilian population. The prisoner newspaper Der Lagerspiegel also bears witness to a rich cultural life – including “cabaret, concerts and Punch-and-Judy shows”.

Nevertheless, Roland Berger later complained that the punishment was too much for his father. “The hero of my childhood had become a man who no longer hoped for a fair chance in life.” The father had laboriously built up a new existence as an independent sales representative. “But in business – his great passion in the past – he never really achieved anything really big.”

The son is quite different: Roland Berger made a name for himself in the post-war history of the German economy like no other. On Monday, his foundation will present the Roland Berger Human Dignity Award 2019 at the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

The interview

“Painful doubts”

Management consultant Roland Berger and Jewish historian Michael Wolffsohn talk about the dark sides of Berger’s father Georg and the question: Is this a case of deliberate whitewashing or a tragic case of self-deception?

The interview Roland Berger is facing on October 11 in the light-flooded rooms of his Munich office high above Maximilianstrasse is not an ordinary one. The 81-year-old did not come alone either: Ellen Daniel, the head of communications of his foundation accompanies him, as well as a second PR consultant and the renowned historian Michael Wolffsohn.

The preparation has a reason. Today it is not about the topics that are usually discussed passionately with the management consultant legend: Europe, Brexit fears, forecasts for the world economy. This time Berger himself is the subject – and especially his father Georg.

Mr. Berger, for many years you have spoken about your father repeatedly and in detail in interviews, whom you described as a Nazi victim. Now, Handelsblatt research has revealed that Georg Berger was a profiteer of the regime during the Nazi era. How do you explain this discrepancy?

Roland Berger: First of all, I can only say that the image I had of my father until now comes from his own stories, from my mother’s memories, and from the reports of relatives and friends who knew him during the Nazi era and often visited us after he returned home from Russian captivity. It all seemed plausible to me. For example, I experienced how the Gestapo repeatedly searched our house in Vienna between 1942 and 1944. Sure, at that time I was still a small boy who could not interpret the overall context. But the pictures of the Gestapo henchmen in our house have remained vivid in my memory.

What concrete memories do you still have of your father?

Berger: On September 12, 1944, for example, I visited the Munich headquarters of the Gestapo in the Wittelsbacher Palais with my mother and my sister where I was able to recite a few poems to my father on his birthday. Then we had to leave again quickly. The image I had of my father was very solid until your call and the first hints about his background followed that shook me deeply.

How did it come about that you only began to talk about your father’s life in interviews about 15 years ago?

Berger: For my 70th birthday in 2007, the Econ publishing house wanted to publish my autobiography.

But you gave the first interviews with him back in 2003. Did the preparatory work start that early?

Berger: Around this time, I started thinking about setting up a foundation and thus also started to deal with my life and family history. In any case, the author appointed by the publishing house did her own research for the first time, the results of which largely coincided with my findings…

… which assumed that your father returned his NSDAP party book after the so-called “Reichskristallnacht” in 1938 – in protest against the anti-Semitic excesses at that time? That he was followed by the Gestapo afterwards? That he was allegedly even imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp, as you have often explained?

Berger: Yes, at that time I had no reason to really doubt my image of him. Now, of course, I want to know everything. And that’s why, after the first hint of Handelsblatt, I also asked the historians Michael Wolffsohn and Sönke Neitzel to clear the air and clarify everything that needs to be clarified. This is to be fully documented in the coming months. I want to know the truth – and then also change my image of my father and take back my earlier statements, if that is necessary. Things and life stories are often not just black or white, but grey…

…although in your stories, your father was a devout Christian and an opponent of the Nazis.

Berger: If it should turn out that I have purported wrong facts, I sincerely regret that – and will publicly correct it.

Among other things, you said in interviews that your father had joined the NSDAP in 1933.

Berger: No, 1931.

You mentioned both numbers from time to time. And the – wrong – date 1933 is the more flattering, of course. Once the National Socialists had seized power, millions of Germans flocked to the NSDAP. Your father was early.

Berger: Yes.

You mentioned the Econ publishing house earlier, which wanted to publish your life story. Why was this book, your autobiography, never published?

Berger: That had nothing to do with the Third Reich.

Your father’s career as a Nazi must have played a part in that, too.

Berger: Among other things, the manuscript listed a number of clients of the management consultancy to whom we as consultants are obliged to maintain confidentiality, even after done deals. There were different opinions about structure and language style, it was supposed to be published in the first person style.

Our research has revealed, among other things: Your father did not leave the party in 1938 in protest. He worked as the supreme administrative head of the Hitler Youth and was personally appointed Ministerial Councilor by Adolf Hitler in 1937. In 1939, he asked Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess for a letter of thanks, which he did receive.

Michael Wolffsohn: I have only been working on the case for two weeks, in collaboration with my colleagues Neitzel and Scianna from the University of Potsdam. We will examine and then evaluate everything. So you have an enormous lead here – and you are right about the facts mentioned. What Mr. Berger said about this in interviews I only know cursorily. To Hess’ letter of thanks: Berger did not receive the title “honorary”. This is relevant. Here, too, the How and Why has to be examined carefully. For historians, sources and the verification of sources go hand in hand.

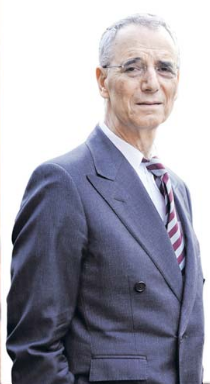

Vita

Roland Berger

Roland Berger

Photo: picture alliance / SZ Photo

Childhood: At birth, Roland Berger was still called Roland Altmann. His father Georg Berger married his mother later on as his second marriage.

Career: Berger founded his first company at 20: a laundromat. At 24, he worked for the Boston Consulting Group. Five years later, Berger went into self-employment and became Germany’s most famous and influential consultant.

Donor: In 2008, the Roland Berger Foundation was established, endowed with 50 million euros from his private assets. It promotes talented children and young people from socially disadvantaged families.

“Things and life stories are often not just black or white, but grey…”

– Roland Berger

But you will understand that we also have to rely on Roland Berger’s interviews as a source.

Wolffsohn: Every source, especially NS sources, require source verification.

From 1941, Georg Berger headed the “Aryanised” Viennese company Ankerbrot as general director and from then on, him and his wife and family lived in an aristocratic villa, which had previously belonged to a Jewish family.

Berger: During this time, many people were guilty and took advantage of Aryanization. This was wrong and cannot be justified – even if the house was not transferred to my father and he paid rent.

Wolffsohn: As far as can be determined so far, Georg Berger was indeed a profiteer of the NS system. That seems clear. The fact that he is supposed to have been a perpetrator cannot be determined from the current state of my research.

Berger: At that time I was not even ten years old yet. How was I supposed to know all this, let alone understand it?

In Vienne, your father was introduced into his position as the boss at Ankerbrot by the NSDAP giant Alfred Proksch. Such treatment is not exactly given to opponents of the system.

Wolffsohn: We will research this thoroughly and publish all details accordingly.

Mr. Berger, in April 1942, the Gestapo did indeed come to your house – albeit on the basis of various charges for violations of the Wartime Economic Order. It was about your father allegedly hoarding food on a large scale.

Wolffsohn: Whereby you surely know how seriously many of these Gestapo files should be taken. These were often also instruments of denunciation.

Some should certainly be regarded just as critical as denazification documents, which were often embellished after the war by the testimony of old friends, neighbors and relatives.

Wolffsohn: Both is true.

Our conclusion is that he apparently did not cause offence for political reasons, but for economic reasons. In September 1942, he had to vacate his post, but refused to leave his service villa. Do you know the outcome of his trial on the grounds of war crimes?

Wolffsohn: Believe me, we will turn over every stone and show no consideration whatsoever. But we’re just not there yet. Quality and depth come before speed. I’m asking for a little patience here.

We could also not find any evidence that Georg Berger was first imprisoned by the Nazis and later by the Americans in Dachau, as has often been claimed. Nor did we find any evidence that the father served on the Eastern Front.

Wolffsohn: Apparently he wasn’t in Dachau during the NS era. He was definitely not on the Eastern Front in Poland or the Soviet Union. What else do you understand by “Eastern Front”?

You better ask Roland Berger. He was the the one talking about this often in interviews.

Wolffsohn: Georg Berger was a soldier in Eastern Austria. We know that for a fact. As a non-historian, Roland Berger does not need to be familiar with the specialist terminology. When I read Ostfront, I feared of war crimes by Berger in the Soviet Union. This topic must be methodically based on worst-case scenarios. So far we have no evidence of this. I don’t want to defend Roland Berger’s language hickups, but he is an amateur in the field. An amateur who worshipped his dad.

We fully understand such personal bonds. On the other hand, he then went into great detail about his father and his supposed role as a victim for more than 15 years.

Wolffsohn: I think we can agree on this: Father Berger was not a victim.

With all due respect: Couldn’t you have noticed this much earlier, even: had to?

Berger: I can only repeat: it all seemed plausible to me – especially based on my own experiences. I had no reason for doubts, which that could have set in motion a process of rethinking.

You even called your father a “moral role model”. With today’s knowledge, would you still maintain this assessment?

Berger: In this context, certainly not any more, even though I have experienced other things with him that still seem exemplary to me today.

How often did you actually see him after the war?

Berger: After the war I only saw him again after his Russian captivity. He returned a broken man. My contact with him was most intensive during years in Vienna years. He was not allowed to work then. Later on, I only met him on the weekends. He died and was buried in Egglkofen, my mother’s hometown.

When?

Berger: He died in 1977, at the age of 84.

What did your father do initally after the war?

Berger: He tried his hand as a sales representative for a few years. But honestly: he was miserable. After all, he was no longer allowed to take on any managerial duties.

That could have made you suspicious, too.

Berger: We will still have to work through why he was imprisoned by the Russians and later interned by the Americans. We have to get to these documents first.

Since 2008, you have been awarding an annual “Prize for Human Dignity” – also in memory of your father, as you explained when the Foundation was established.

Berger: Well, it’s not in the foundation charter. That is all about the protection and promotion of human dignity worldwide and the remembrance of injustice, not least during the Nazi era and the Holocaust.

We don’t want to question the award. The purpose of the foundation is highly honorable. But on 27 March 2008, when you handed over the foundation deed, you gave a speech in which you talked about your father’s fate. Isn’t it possible that this was also about misleading the public?

Berger: I can’t see it that way. I have judged my father’s life to the best of my knowledge and belief. Today I am smarter – also due to the new facts and documents. But I never intended to deceive. Why would I do that?

Your prize was awarded for the first time on 24 November 2008. Nine days earlier, you received the Prize for Understanding and Tolerance from the Jewish Museum in Berlin. In April 2013, in return, this museum was awarded the Roland Berger Prize.

Wolffsohn: But relationships such as those are not linear and mono-causal. Roland Berger is not seen as the initiator of an award by the Jewish community, but as a person who has many merits. By the way, the Jewish Museum was never and is still not a representative of the German Jewish community, but a state museum.

And we do not want to question this lifework either. But the fundamental question is simply whether we are witnessing a case of deliberate whitewashing or tragic self-deception. Get the picture?

Wolffsohn: Of course are both variants theoretically conceivable. But it is far more plausible here that first a very young and then a grown-up man has glorified his father in retrospect … to what extend, that is what we will clarify in the next few weeks.

Berger: If you will: Yes, then it must have been an unintentional “tragic self-deception” that I am guilty of. I do not imagine, though, that it would be easy to resign from office in such a regime in 1939. But a resignation is not an act of resistance.

Wolffsohn: And believe me: I have experienced and researched a lot about coming to terms with the past – both brown and red history. I think it is very good how openly Mr. Berger is dealing with all the possible results of our further research.

Berger: In a way, I am grateful to Handelsblatt that you have raised these painful doubts about my image of my father in me, and have thus brought the truth closer.

Mr Berger, Mr Wolffsohn, thank you very much for the interview.

The questions were asked by Sönke Iwersen, Andrea Rexer and Thomas Tuma.

“If it turns out that I have claimed the wrong things, I sincerely regret it.”

– Roland Berger

Vita

Michael Wolffsohn

Michael Wolffsohn Photo: Markus Nowak/KNA

Origin: Wolffsohn was born in Tel Aviv in 1947 as the son of a Jewish merchant family. His grandparents were victims of the “Aryanization” in Germany.

Work: The historian is considered one of the most knowledgeable experts on German-Jewish-Israeli relations.

Honoured: bearer of the Federal Cross of Merit and numerous other international awards.