Investigative

Reporting

Award 2019 Nominee

Money laundering at Danske Bank

Simon Bendtsen

Michael Lund

"This investigation is now globally known as the biggest money laundering case yet uncovered. Investigative journalism at its finest", says Uffe Riis Sørensen, member of the European Press Prize preparatory committee.

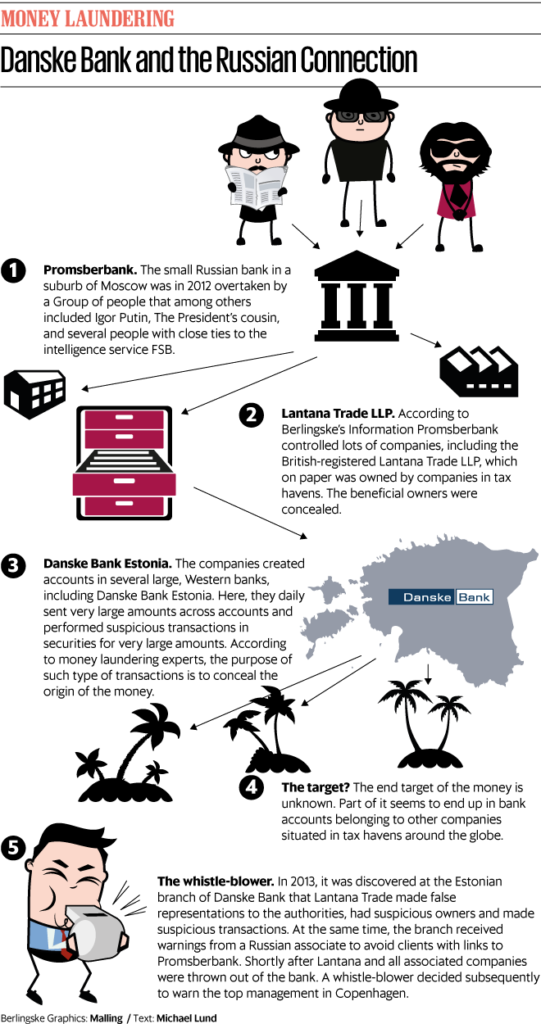

Family members of Russia’s President Putin and FSB, the Russian intelligence service, were allegedly behind efforts to launder money through Denmark’s biggest bank, claims a whistleblower who alerted top management at Danske Bank in 2013. This information, which has only now come to light, indicates that top management was aware of far more serious conditions than the bank has previously indicated.

Photo credit: Thomas Lekfeldt/Berlingske

Members of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s family and the Russian intelligence service FSB are alleged to have been behind substantial money laundering using accounts held with the Estonian branch of Denmark’s biggest bank. The information stems from a whistle-blowing report which was written by an executive within Danske Bank and sent directly to the bank’s top management in Copenhagen in December 2013.

According to the report, “apparently it was discovered” at Danske Bank’s Estonia branch in 2013 that certain individuals behind a suspicious company which held accounts at the bank and which was making “suspicious payments” also “included the Putin family and FSB”.

Berlingske has information that the alert included Vladimir Putin’s cousin, the businessman and politician Igor Putin, as well as a number of individuals closely linked to the top of the FSB. The detailed whistleblower report, which Berlingske has had access to, also warned Danske Bank’s management that the bank “may itself have committed a criminal offence”, “has likely breached numerous regulatory requirements”, “behaved unethically” and likely was “helping to launder money”.

The whistleblower also pointed to a “near total process failure” in the branch’s anti-money laundering controls. “Just when you thought this money laundering case couldn’t get any more serious for Danske Bank, it did,” says Jakob Dedenroth Bernhoft, an expert on anti-money laundering regulations and CEO of the advisory firm Revisorjura.dk who has been following the case closely.

“Just when you thought this money laundering case couldn’t get any more serious for Danske Bank, it did.”

“This new information shows that this is a completely unique case with foreign-policy ramifications that go almost far beyond anyone’s imagination,” he says.

The new information shows that Danske Bank’s top management knew as early as 2013 that there were far more serious breaches at the Estonian branch than what the bank has since indicated.

Until now, the top management has explained it was merely aware that anti-money laundering controls were too insufficient back then to prevent the Estonian branch from “potentially being used for money laundering”.

Only last year – after Berlingske revealed actual instances of money laundering – did CEO Thomas Borgen launch an extensive investigation, stating that the problems appeared “worse than feared”.

It is thus spectacular to find that, as early as 2013, the top management actually had detailed knowledge that the intelligence service of a foreign state and the family of Russia’s president were likely conducting suspicious money transactions with the help of the bank, says Ole Risager, a professor at Copenhagen Business School (CBS) approached by Berlingske to comment on the case.

“It’s self-evidently very serious if the management was told internally that the bank was probably laundering money for people in the Russian intelligence service,” he says.

“Why did they not start a major investigation back then? It seems odd that the management is only reacting now, after Berlingske’s revelations, if they already had such clear indications of extensive money laundering back then,” he states.

Ole Risager is also critical of the fact that this investigation is being conducted by Danske Bank itself, while neither the Danish financial services regulator, Finanstilsynet, nor the police financial crime unit, SØIK, have indicated that they are investigating the matter.

“In a society based on the rule of law authorities obviously need to launch an impartial and thorough investigation of the entire matter.”

Suspicious payments

The whistleblower‘s report was sent on 27 December 2013 to Danske Bank’s head office in Copenhagen and addressed to Mr. Robert Endersby who was then the head of the bank’s credit and risk management team and the right-hand man of CEO Thomas Borgen.

The report was also sent to Mr. Ivar Pae, head of Danske Bank’s Baltic activities, as well as the executives responsible for Danske Bank’s anti-money laundering efforts and the bank’s internal audit function.

None of them wished to make a statement to Berlingske.

The report describes the following turn of events:

In the summer of 2013 the Estonian branch became aware that a client with the branch, a UK-registered company by the name of Lantana Trade LLP, had made false representations in its financial accounts to the British authorities.

Among a number of issues, the company reported extremely low turnover figures and was registered as being inactive despite a daily flow of large sums of money through the company’s bank accounts.

According to the whistleblower’s report the company was also making “suspicious payments”, and the branch did not hold sufficient information concerning “who the beneficial owners were”.

The branch therefore started to investigate Lantana Trade LLP and about 20 associated companies which were frequently transferring large amounts to each other across accounts held with Danske Bank Estonia.

According to the whistleblower’s report, “apparently it was discovered that they included the Putin family and FSB”.

According to the whistleblower’s report, “apparently it was discovered that they included the Putin family and FSB”.

The report also points to these companies’ “beneficial owners having been involved with several Russian banks that had been closed down in recent years”.

The president’s cousin

Berlingske contacted several sources close to the matter to verify and expand on the information contained in the report. All sources spoke independently of each other.

According to these sources, the information relates specifically to a circle of individuals including Igor Putin, the businessman and politician who is a cousin of the Russian president, and people with close ties to the top of the Russian intelligence service FSB.

Berlingske has tried unsuccessfully to contact Igor Putin through his fund.

Several media have described how the same group of individuals spent a number of years taking over several small Russian banks, including Promsberbank based near Moscow.

Some of these banks subsequently went bankrupt or were closed down by the authorities after discovering large suspicious sums of money flowing out of these banks and out of Russia.

“Some of these banks subsequently went bankrupt or were closed down by the authorities after discovering large suspicious sums of money flowing out of these banks and out of Russia.”

Berlingske has learnt that this was the reason why Danske Bank’s Estonian branch received warnings from a Russian associate in 2013 to avoid any client linked to Promsberbank or the individuals behind this bank.

Hence it caused major concern at the Estonian branch when, later that year, it found clear links between companies in the Lantana group and Promsberbank, says one of Berlingske’s sources who is a former employee at Danske Bank Estonia.

The source has chosen to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals from Danske Bank and the people behind Promsberbank.

“Our internal investigation showed that Lantana Trade LLP was associated with highly-ranking employees in Promsberbank. The company and cash flows were controlled by the bank. It was not just rumors, by our opinion it was very valid information.”

Threats, fines and prison time

Danske Bank Estonia then immediately contacted Lantana’s Russian representatives to enquire about the owners’ identities, but according to several sources this request did not go down well.

One Danske Bank staff member was reported to have left an unpleasant meeting in Moscow in a state of shock. Shortly after, staff at the Estonian branch were contacted by Russian-speaking individuals who refused to state their identities and instead threatened staff: “The bank will sink after this” and “Do you really feel you can walk home safely at night?”

‘Staff at the Estonian branch were contacted by Russian-speaking individuals who refused to state their identities and instead threatened staff: “The bank will sink after this” and “Do you really feel you can walk home safely at night?”’

Shortly after, Danske Bank Estonia chose to shut down Lantana’s accounts and those of some 20 associated companies which were frequently exchanging suspiciously large amounts of money with each other and with Lantana through accounts at the branch.

It has since become clear that this group of clients was also behind other illegal activities.

Several of the approximately 20 companies – IC Financial Bridge, Cherryfield Management, Chadborg Trade and Ergoinvest – were at the centre of another international money laundering scandal which last year saw Deutsche Bank agree to substantial fines.

In that case, the companies were found to have carried out large-scale money laundering by engaging in a process known as mirror trading, involving the use of stock trades.

According to Bloomberg News and The New Yorker, Igor Putin and the same individuals associated with the FSB are also alleged to have been behind the fraud involving Deutsche Bank.

A Russian middleman, Alexei Kulikov, was also kicked out of Danske Bank Estonia along with the 20 companies. He is now in prison for his involvement in major fraud at Promsberbank. Berlingske has not received a response to a letter sent to him in prison. All 20 companies have since been closed down.

Well-known methods

Danske Bank has previously stated that its top management in Copenhagen was alerted to the money laundering problems in Estonia by a whistleblower, but the bank has consistently refused to publish any further details concerning these warnings.

CEO Thomas Borgen has given the following written response:

“We have launched a thorough investigation to get to the bottom of the events at that time in our Estonian branch. We are unable to comment the matter further, until the investigation has finalised. Furthermore, we are unable to comment on specific customers, but the entire portfolio in question (non-residents) has been closed down.”

Later in 2014, the whistleblower’s report led the bank to launch a major review in order to clean up the thousands of companies which held accounts with Danske Bank Estonia’s section for non-resident clients.

This work was only concluded towards the end of 2015 – a full two years after the Lantana group had been kicked out.

“As we have previously said, on the basis of what we know now, we should have done this faster. Today, we have a very different and stronger control setup in Estonia,” Thomas Borgen states.

Berlingske has not been able to confirm whether Danske Bank fully disclosed its information on these companies to the relevant authorities.

Madis Reimand, the head of Estonia’s Financial Intelligence Unit, said he is unable to comment on specific companies and transactions but recognizes the methods and mode of operation used in this case: “Generally speaking the purpose of such money laundering schemes is to move the funds out of Russia, to get the money in to the western financial system and do it in an untransparent and secretive manner.”

CBS professor Ole Risager has previously worked in the Baltic region as a senior economist with the International Monetary Fund and has extensive knowledge of the Baltic financial sector.

He calls it a “realistic and likely scenario that the money came from illegal activities”.

“The money may have been stolen from state companies or stem from bribery or extortion. It may also have been an attempt to bypass international sanctions which Russia’s rich oligarchs have been subjected to for a number of years,” he says.

“The money may have been stolen from state companies or stem from bribery or extortion.”

L. Burke Files, a partner of US advisory firm Financial Examinations and Evaluations and an expert on financial investigations, says that US authorities would likely be extremely interested in this case and probably have already started investigating it, as it involves large transactions denominated in US dollars.

“There has to be some individual culpability here – some had to choose to ignore the klaxon horn that this account and others raised. Someone chose not to look or to investigate,” he says.

Jakob Dedenroth, the Danish expert on anti-money laundering regulations, agrees: “If there is any truth to the whistleblower’s allegations, then it is not just a matter of the bank’s culpability but also whether the management at Danske Bank Estonia could be held directly responsible,” he says.

Berlingske has sought to get a comment from the whistleblower in question, who was then an executive with the bank. The whistleblower declined, referring to Danske Bank for any comments.

Berlingske also presented the matter to the Russian authorities through the Russian embassy in Copenhagen but did not receive a response.

Translation by Bibi Christensen.