Investigative

Reporting

Award

Thousands of Hospital Patients Are Dying from Terrible Infections. Instead of Addressing the Situation, the Government Is Working to Cover It Up

published by Direkt36.hu, Telex.hu, Hungary

“If I stay here, I will die,” Bálint told his fiancé Marianna one summer day in 2015, as he had been suffering completely weakened from weeks of unstoppable diarrhea in the internal medicine ward of Budapest’s Péterfy Sándor Hospital.

The man, who was then in his thirties, athletic, and working as a mid-level manager for a company, was recovering from surgery when he contracted clostridium difficile – an infection that commonly spreads in hospitals. The pathogen is resistant to alcohol-based disinfectants and can spread rapidly among patients who are lying in hospital beds, often in diapers and unable to move – all it takes is a missed hand wash, a poorly disinfected door handle, or an uncleaned toilet.

Bálint was eventually cured in another hospital thanks to Marianna’s personal efforts, but he still suffered serious consequences from the infectious disease. He lost 8 months of his life, 40 kilos of his weight and developed three hernias.

Bálint is one of the thousands of people who in recent years have had to endure unnecessary suffering and even fatal complications from infections contracted in the very place where they went to recover: the hospital.

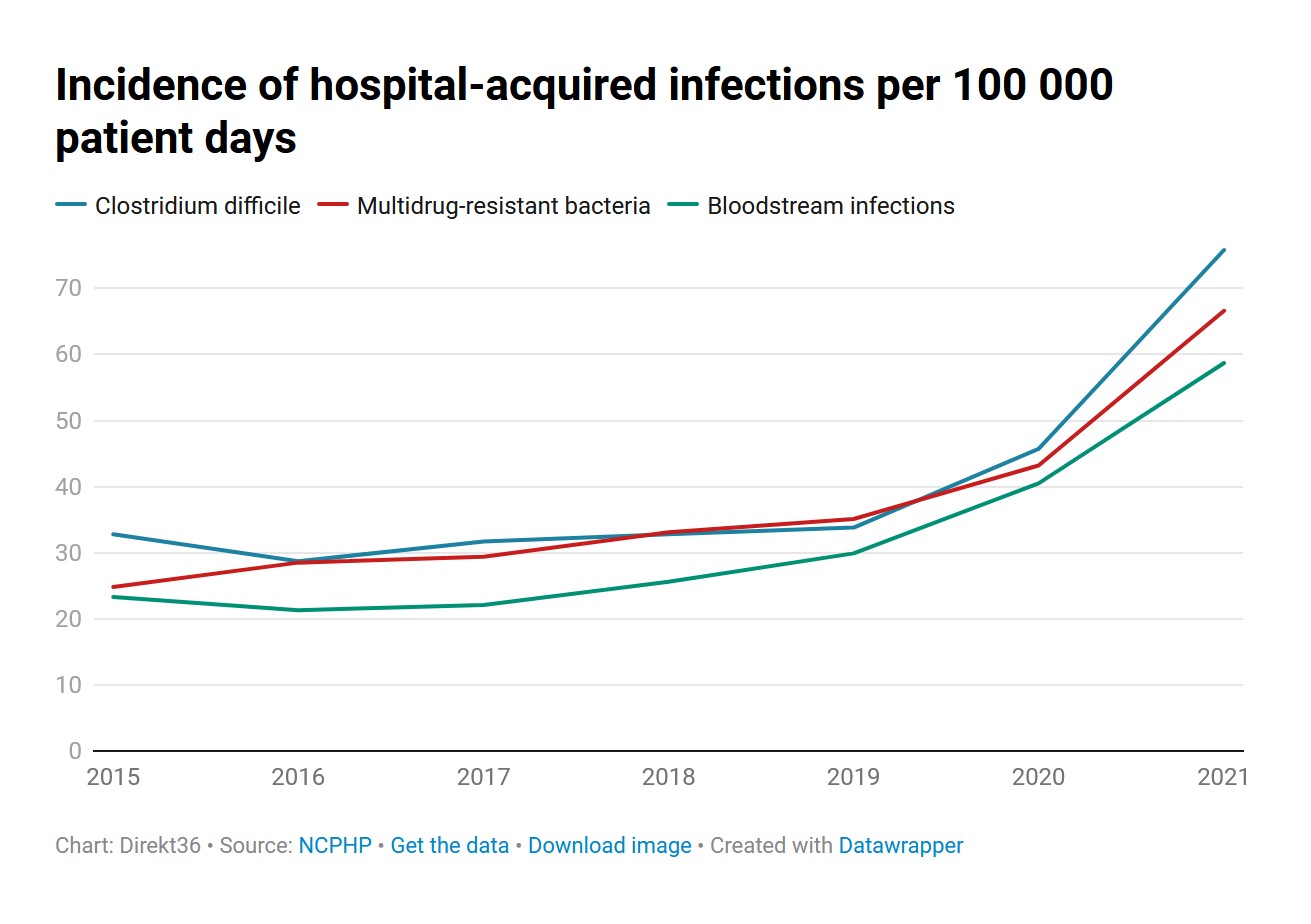

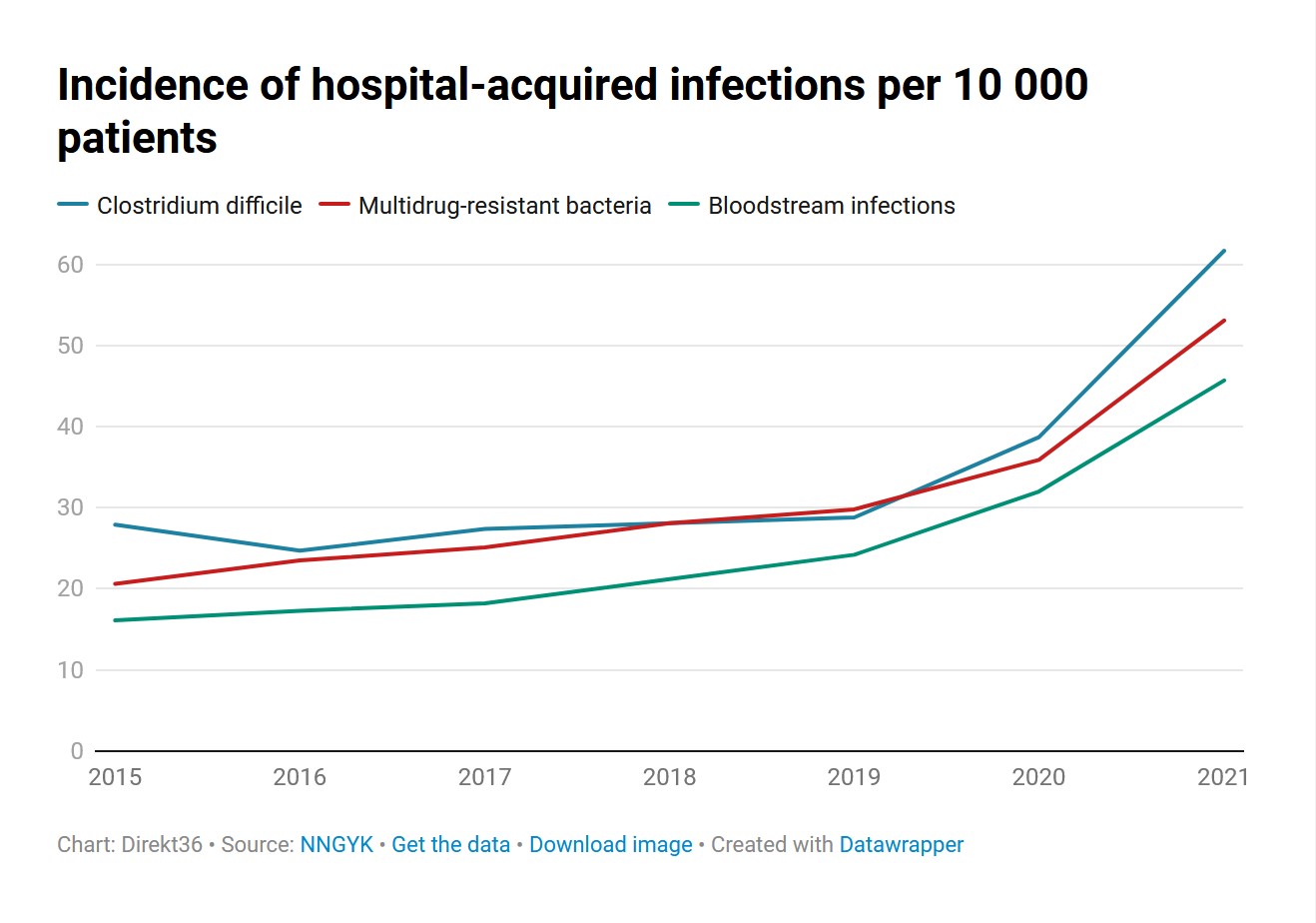

The number of hospital-acquired infections in Hungary has been rising steadily for many years. Hospitals are reporting more and more cases every year: in 2021, a previously unimaginable number of hospital-acquired infections were identified, some 16-21 thousand depending on the calculation, almost half of which resulted in death. In 1400 of these cases, the hospitals themselves admitted that the hospital-acquired infection played a role in the death of patients. Data on 2022 was not available before the publication of this article.

However, these figures do not fully reflect the actual situation. In 2017 a detailed European study found that more than 78,000 hospital-acquired infections occur in Hungary every year, meaning that 3.5 percent of people admitted to hospital (almost one in 25 people) contract an infection. This is several times higher than the number of hospital-acquired infections reported by the National Centre for Public Health and Pharmacy (NCPHP).

While the problem is obvious, the government and state authorities are not making serious efforts to solve it. Moreover, they are doing everything they can to hide from patients – and even health workers – how serious the situation is, and which hospitals should pay more attention to reducing infections.

However, Direkt36 has uncovered many new details about hospital-acquired infections during a year-long investigation. The main findings of our investigation called the Semmelweis Project and our accompanying documentary film, are the following:

- The Hungarian state and politicians are aware of the seriousness of the problem, but they put more energy into denying it and sweeping it under the carpet than solving it;

- using various methods, they intentionally hide what is going on in certain hospitals, not to “scare the public”;

- we prove that the situation is even more serious than what official statistics show and that in reality there are significantly more hospital-acquired infections;

- with the help of experts, we have prepared and are publishing a uniquely detailed analysis unprecedented in Hungary, based on data from a few years ago. Based on this analysis, it can be determined how certain departments of hospitals and the hospitals themselves compare to each other regarding hospital-acquired infections;

- we provide a closer look into what is happening behind the walls at several hospitals with exceptionally high numbers of infections in our rankings

- in several indicators, Hungary is underperforming in European comparison: small amount of hand disinfectants is used, there are few laboratory tests, few nurses, while there are still many multi-bed wards. These factors all contribute to the spread of infections.

For this investigation, we traveled from inside and outside Hungary, conducted more than 30 interviews and background interviews, and reviewed hundreds of pages of technical reports. We obtained tens of thousands of rows from previously undisclosed data on hospital-acquired infections, which we have made interpretable and analyzed over several months.

Our analysis was based on a raw database obtained from the state through a lawsuit by the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU). It contains details of all reported hospital-acquired infections from three years before the Covid outbreak. The analysis was supported by a renowned biostatistician who spent many hours using several complex statistical models to produce the ranking of hospitals in the country.

In the meantime, we and the HCLU have filed a lawsuit for the latest data available on hospital-acquired infections, as the NCPHP continued its efforts to prevent its disclosure – ignoring the fact that several courts have already ruled that it cannot withhold these data.

The Ministry of the Interior, which is responsible for the healthcare system, has not responded to our questions, nor has the National Directorate General for Hospitals (NDGH), which oversees the hospital’s day-to-day operations. We have interviewed the Head of the NCPHP’s Hospital Hygiene and Regulatory Division, whom we quote several times in the article, but she stressed that they only make professional recommendations to hospitals and that it is up to the holspitals’ management and the state to provide the necessary resources.

What is spreading in hospitals?

Pathogens spreading in hospitals are typically resistant to concentrated disinfectants and strong antibiotics. They are known as multiresistant bacteria and can cause serious illness by infecting elderly or immunocompromised people in hospital beds who are already ill.

There are a wide range of them, from acinetobacter baumannii, which can cause pneumonia, wound infections and urinary tract infections, to the bacteria MRSA which can cause abscesses and wounds to fester and heal difficultly. The latter is a type of pathogen that can enter the bloodstream and cause fatal blood poisoning (sepsis). Other common pathogens include the already mentioned clostridium difficile, a spore-forming bacteria, which causes foul-smelling, mucousy diarrhea and even severe inflammation of the intestines. Alcohol-based hand sanitizer by itself is not effective against it.

Pathogens can be spread by droplet transmission, faeces, wound drainage, through medical equipments and to a significant extent by the insufficiently disinfected hands of a doctor, nurse or visitor. Without proper hygiene, pathogens can linger on medical equipment, hospital toilets, door handles, shower curtains, bed linen, nurse call buttons – almost anywhere. Any invasive procedure, such as surgery, as well as a tube, catheter or cannula sticking out of a patient, poses a risk of infection. The longer a person spends in the hospital, the more likely they are to become infected. And even die as a result.

This is a problem not only in Hungary, but in hospitals all over the world. More and more superbugs are appearing and spreading. The difference is in how countries’ healthcare systems handle the problem: whether they tackle it and keep it under control or succumb to it and sweep it under the carpet. There are not only billions spent on treatment, but also lives at stake: if done right, 30-50 percent of infections can be prevented, according to globally accepted estimates.

The personal story of Bálint presented at the beginning of this article illustrates, however, that not enough is being done in Hungary concerning prevention.

By 2015, the young man had been struggling with recurrent colitis for several years, leading to his admission to Péterfy Hospital, only to get worse after two weeks. He was visited every day at the hospital by his fiancé Marianna, who eventually managed to persuade the doctor to conduct an imaging scan. It revealed his bowel was perforated and his faeces had been leaking into his abdomen for weeks. He immediately underwent life-saving surgery.

Bálint was recovering in intensive care and was given antibiotics, yet after a few days he came down with another fever and complained of severe diarrhea. “Afterwards, I went to the doctors again to say that we thought he had caught something, but they didn’t listen to me”, recalled his fiancé.

Marianna then gave up on the help of the hospital doctors and took Bálint’s stool sample to a private laboratory herself. There it was confirmed that he had contracted clostridium difficile infection during his days in hospital. Although this allowed them to identify what was wrong with Bálint, Marianna claims the doctors frowned upon her private action.

“How can I do this when they are doing everything”, Marianna explains the doctors’ reaction after she showed them the results of the private lab.

Even though Bálint had been suffering from a severe clostridium difficile infection for weeks and a laboratory examination confirmed it, he was not isolated but placed in a three-bed ward in the internal medicine department. The man also had to use the same toilet down the corridor – every ten minutes – as everyone else. It was at this time he felt his survival depended on being placed in better conditions. Eventually, a private doctor helped him get admitted to Budapest’s Honvéd Hospital, where he ultimately completed his treatment with antibiotics.

Péterfy Sándor Hospital did not respond to Direkt36’s request for comment.

Transparency is a bad idea according to the state

In the United States and England, patients can check the risk of infection with hospitals or the trusts that operate hospitals. This is not possible in Hungary, and the authorities have long argued that it should not be.

“When will it be that when I’m about to have an operation in a hospital, I can find out how said hospital is doing in terms of hospital-acquired infections online?”, György Baló asked his guest, epidemiologist Beatrix Oroszi, on his TV show back in 2017. “In the next few years, that is unlikely to happen, and I would not consider it right,” replied Oroszi, then head of the National Centre for Epidemiology (an organization that has since been dismantled).

This was the last time that experts from the authorities responsible for monitoring hospital-acquired infections have publicly challenged those who have called for more open communication about hospital-acquired infections. At the time, the HCLU launched a campaign and filed a lawsuit for the public disclosure of data on hospital-acquired infections, as the National Public Health and Medical Officer Service (NPHMOS – the predecessor of NCPHP) only published national statistics on the situation once a year, hidden on its website, as they still do today. The text is difficult to understand, the background of the statistics is not explained, and the causes of changes – mostly deteriorating data – are not revealed.

“How individual hospitals are performing is not at all revealed in these annual reports,” Márton Asbóth, legal expert of HCLU told Direkt36.

Asbóth remembers well György Baló’s show, where he was also a guest. “It became clear to me that the people at the NPHMOS have good intentions and understood the issue, but they didn’t understand why we should talk about it publicly. They also felt uncomfortable that we were suing for the data.”

Politicians have followed a strategy of denial. In 2019, MSZP’s MP Ildikó Bangóné Borbély raised the issue of hospital-acquired infections in parliament. However, Secretary of State Bence Rétvári did not even acknowledge the existence of the problem in his answer, instead, he attacked the health policies of the socialist governments and cited a European comparative figure that made it seem like the situation regarding hospital-acquired infections in Hungary was much better than in other EU countries. “So, concerning hospital-acquired infections, a Hungarian patient is safer than an average European patient in an average European hospital,” said Rétvári.

However, the figures quoted by Rétvári are misleading, as the European study to which he – presumably – referred to ranked Hungary among the worst-performing countries in Europe in many other indicators.

For example, the survey conducted by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) every few years – most recently in 2017 – measures the number of laboratory tests. Less testing means more infections remain undetected. An indicator measures the number of haemocultures – the microbiological testing of blood – performed in 1,000 patient days (a full day of hospital care for an in-patient is considered a patient day). In Hungary, this figure is only 3, while in England – the country commonly referred to as the “benchmark” for successful infection control – it is over 45. Hungary, however, is among the worst-performing countries in Europe, as well as in laboratory testing for the aforementioned diarrheal hospital-acquired infection, clostridium difficile. The number of stool tests was 1.3 per 1,000 patient days in Hungary, whereas in England it was over 10.

The NCPHP itself admitted to Direkt36 that the low sample size affects the accuracy of the data. During the lawsuit filed for the latest data on hospital-acquired infections, it was argued, that “low infection rates may be the result of insufficient infection identification rates (e.g. very few blood samples are taken by doctors, so that a low number of bloodstream infections are laboratory-confirmed, which is required for reporting) or loose reporting discipline.”

Despite the previous statement, Dr. Ágnes Galgóczi, Head of the NCPHP’s Hospital Hygiene and Regulatory Division, in an interview with Direkt36, did not admit that the situation is much worse than the figures show. “That certainly cannot be stated,” she replied but did not elaborate on the matter.

The European survey has another telling statistic, in which Hungary also ranked very poorly, second to last in the whole EU. Only 7.4 liters of alcohol-based hand sanitizer were used in Hungarian hospitals per 1000 patient days, while the countries at the other end of the scale consumed well over 50 liters. The EU average is 20 liters.

The survey also found that there were clearly many problems concerning hospital conditions in Hungary. The extreme workload of hospital staff in Hungary was shown by the fact that Hungary had 43 nurses per 100 hospital beds, putting us last among all countries (the same figure for England was 270). The same was true for the proportion of single-room beds, one of the most effective tools for preventing infections. In Hungarian hospitals, 1.4% of beds are in single rooms, the lowest proportion in the EU (France, at the other end of the scale, had 50%).

“It would scare the public”

Behind the government’s denial and secrecy was not just the fact that there was little to be proud of in the case of worsening official statistics. One of the reasons, according to information obtained by Direkt36, was that politicians and public authorities genuinely thought that open communication could cause panic.

A source formerly working in the health administration, who has information about several professional consultations from these years, spoke about this to Direkt36. In such discussions – for example, when infection control days were organized – the argument that “it would scare the public” if they communicated openly about infections was usually put forward according to the source. According to the source, no one was interested in “getting to the bottom of the problem”, although there were infection control campaigns, experimental programmes and there were “some very enthusiastic colleagues in the NPHMOS who were trying to push the issue.” But no overall improvement has resulted from these efforts.

The source told us that even the chief medical officer is not interested in “showing the public how serious the situation is”, as this would also raise their responsibility. This is why public authorities still choose secrecy today.

“The reality is that hospitals are reporting fewer cases than are occurring, and fewer microbiological tests are being carried out than should be. Meaning we are not seeing the reality in the statistics, but the tip of the iceberg”, said the source.

A significant gap between statistics and reality is shown by the European comparative study carried out by the ECDC in 2016-2017, which has been cited several times. They calculated – based on data from Hungarian hospitals – that 78,000 hospital-acquired infections occur in Hungary every year. In those years, Hungarian hospitals reported only slightly more than 10,000 hospital-acquired infections to the NCPHP. The difference between the figures is multiple.

There were promises

In 2018, when Miklós Kásler, Professor of Medicine, became Minister of Human Capacities, it seemed that a turning point was about to be reached in the treatment of infections. In his first interview after his appointment, the minister stated he wanted to take action: “The issue of hospital-acquired infections must be resolved very quickly,” he said on TV2, for example.

Several measures have been taken, for example, a ministerial decree on how to strengthen infection control in hospitals was issued in the summer of 2018. Kásler was very optimistic, stating at the time of the decree’s introduction that following the “protocol change” the number of infections could drop by 30-50 percent. He expects positive results within a week or two, the minister said.

However, these measures did not make a substantial difference, at least not in the following year, according to the NCPHP’s 2019 and 2020 statistics, which they simply suppressed for two years and refused to publish until they faced litigation. The coronavirus outbreak of early 2020 led to a number of new restrictions and hygiene measures in Hungarian hospitals, however, infections have not been reduced as a result. In fact, the figures revealed the contrary.

While measures introduced in Germany and Austria have reduced the spread of several hospital-acquired infections, including clostridium difficile, in Hungarian hospitals not only has the coronavirus spread despite all the hand disinfection, isolation, protective suits, medical masks and rubber gloves, but the spread of already well-known pathogens have also resulted in never-before-seen infection and death rates.

Hospital-acquired infections have been spreading in hospitals ever since, but the topic has died out in the public discourse. But the strategy of secrecy is still in place. Last autumn, Direkt36 tried to obtain detailed statistics on hospital-acquired infections between 2017 and 2021 broken down by hospital from the NCPHP as data of public interest. Since HCLU had already fought in court for the same data – for previous years – and finally won with the decision of the Curia, we expected that this would be a formality and that we would soon have the valuable database in our hands. This was not the case, the NCPHP refused to give us the data, so we had to file a lawsuit with the help of HCLU, which we won in the second instance on 14 September. According to the judgment, it is clear that the data is in the public interest. The NCPHP itself did not dispute this in the lawsuit, but only put forward technical arguments that “the disclosure of detailed data on the institution could be dangerous and mislead the public and patients.”

Until now, it was a secret how Hungarian hospitals were dealing with infections. Direkt36 has created and now publishes its ranking.

As we needed to wait for the end of the trials in order to get the most recent data, we decided to analyze the data available at the time. The original raw database received from the HCLU consisted of four .pdf files containing all the data (excluding personal data) on all hospital-acquired infections reported to the NCPHP between 2014 and 2016: when, where, what type of infection occurred, what underlying diseases the infected person had, how they were treated and what their fate was – whether they died or recovered, and if they died, whether their death was related to the hospital-acquired infection. The files contained a total of 6189 pages, tens of thousands of rows of data on the infections, only they were a complete mess. However, with the help of a team of data analysts and researchers from the international journalism organization OCCRP (Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project), we managed to turn them into a manageable database.

There were a number of obstacles to correctly analysing the data, so we asked Tamás Ferenci, one of the country’s most renowned biostatisticians for help. He has used a total of 21 statistical computing models, and filtered out differences between patients and between hospitals, to produce an analysis that allows an objective assessment and comparison of the performance of individual hospitals. No statistical analysis of hospital-acquired infections in Hungary – at least not one that is publicly available – has ever been carried out to this level of detail.

You can read a longer account of how we worked at the end of this article. You can find Ferenci’s own in-depth methodological description here.

The main findings of the analysis are the following:

- large hospitals treating serious cases do not always have proportionally high rates of infections, and in fact there are some smaller institutions that perform poorly for all types of infection;

- based on the reported infections, there are a lot of problems in Budapest hospitals, as well as in several city hospitals elsewhere in the country. The most affected departments are intensive, surgical and internal medicine wards, but we have also found a case of an outbreak in a psychiatric ward;

- hospitals attribute only a very small percentage of patient deaths to hospital-acquired infections, yet in 30-40% of infection cases the patient dies;

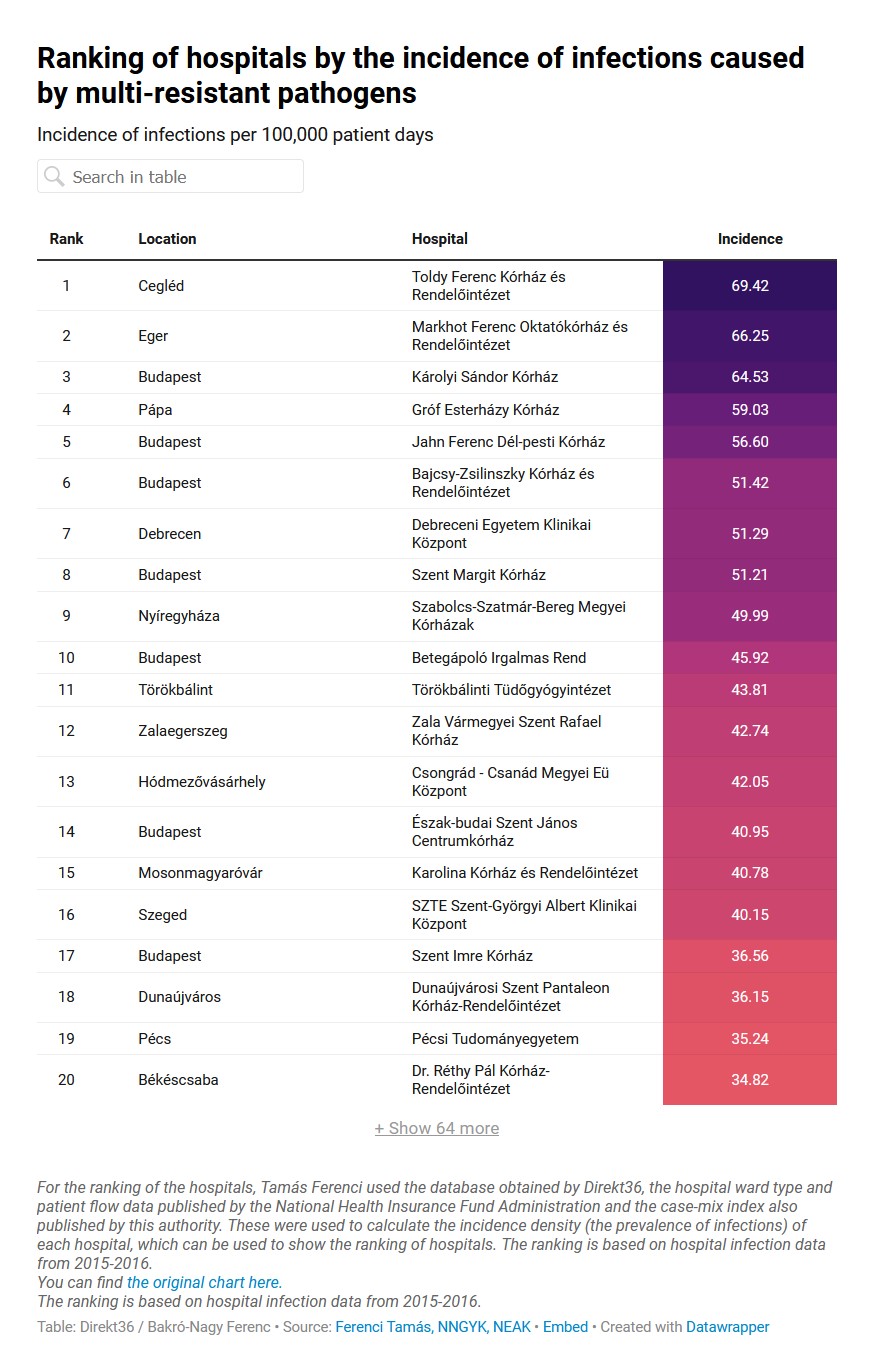

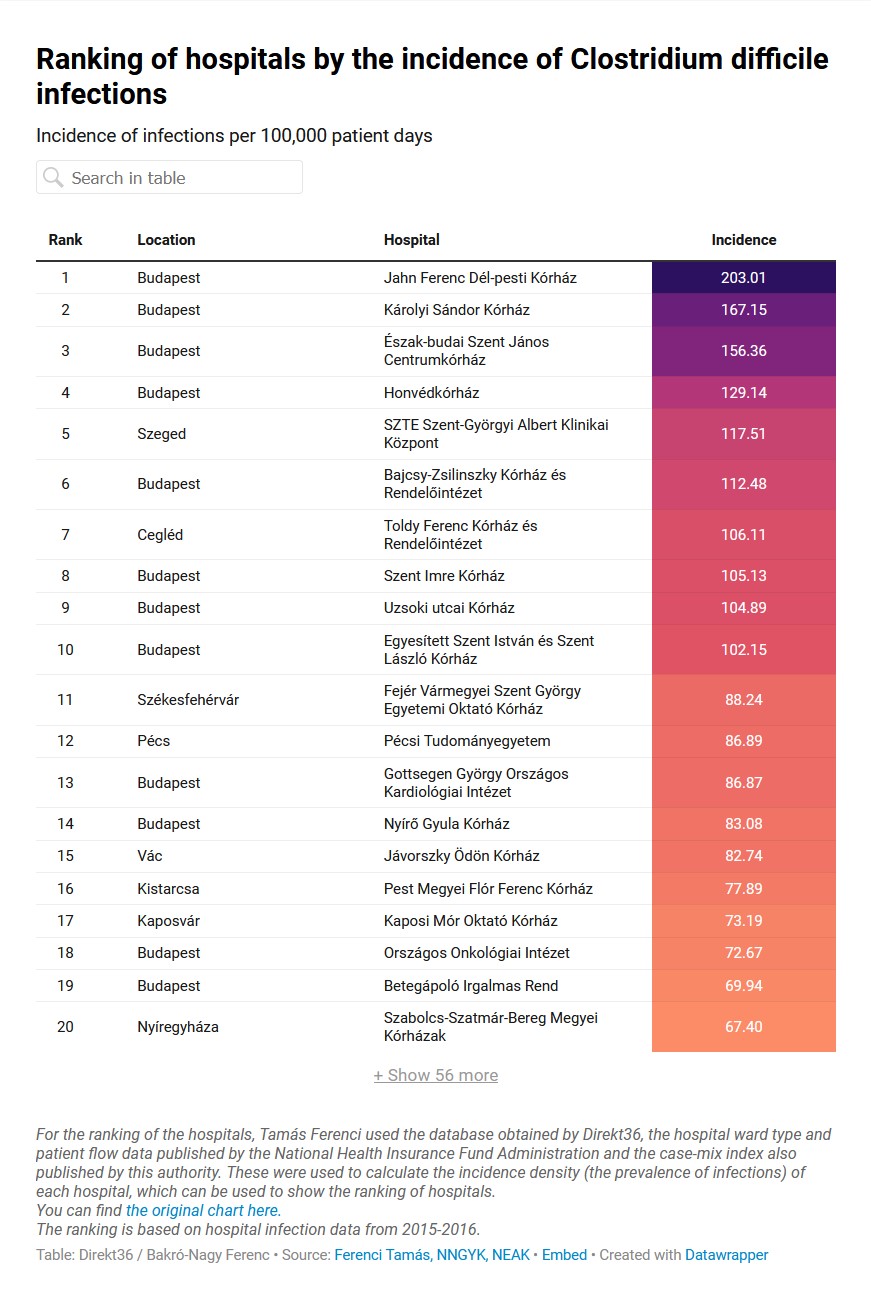

- our analysis identified major problems in the Jahn Ferenc, Károlyi Sándor, Szent János and Bajcsy-Zsilinszky hospitals of Budapest, among others. In the case of pathogens resistant to antibiotics, the hospitals of Cegléd, Eger and Pápa performed very poorly.

The comparison is based on data from previous years, which the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union has obtained from the state through a lawsuit and made available to us. The data is from 2015-16, however, there are several indications that the situation has not changed significantly.

Firstly, hospital-acquired infections have continued to rise year after year, and a record amount of infections were reached during the coronavirus pandemic: by 2021, the total amount of hospital-acquired infections had increased by around two and a half times compared to 2015. The overall trends revealed by the 2015-16 data have not changed either. No data is available for individual hospitals since then, but there is region-specific information in the public statistics of the National Centre for Public Health and Pharmacy (NCPHP). These show that the same regions – mainly Central Hungary and the northern part of the Alföld region – continue to perform poorly every year.

Here are the results

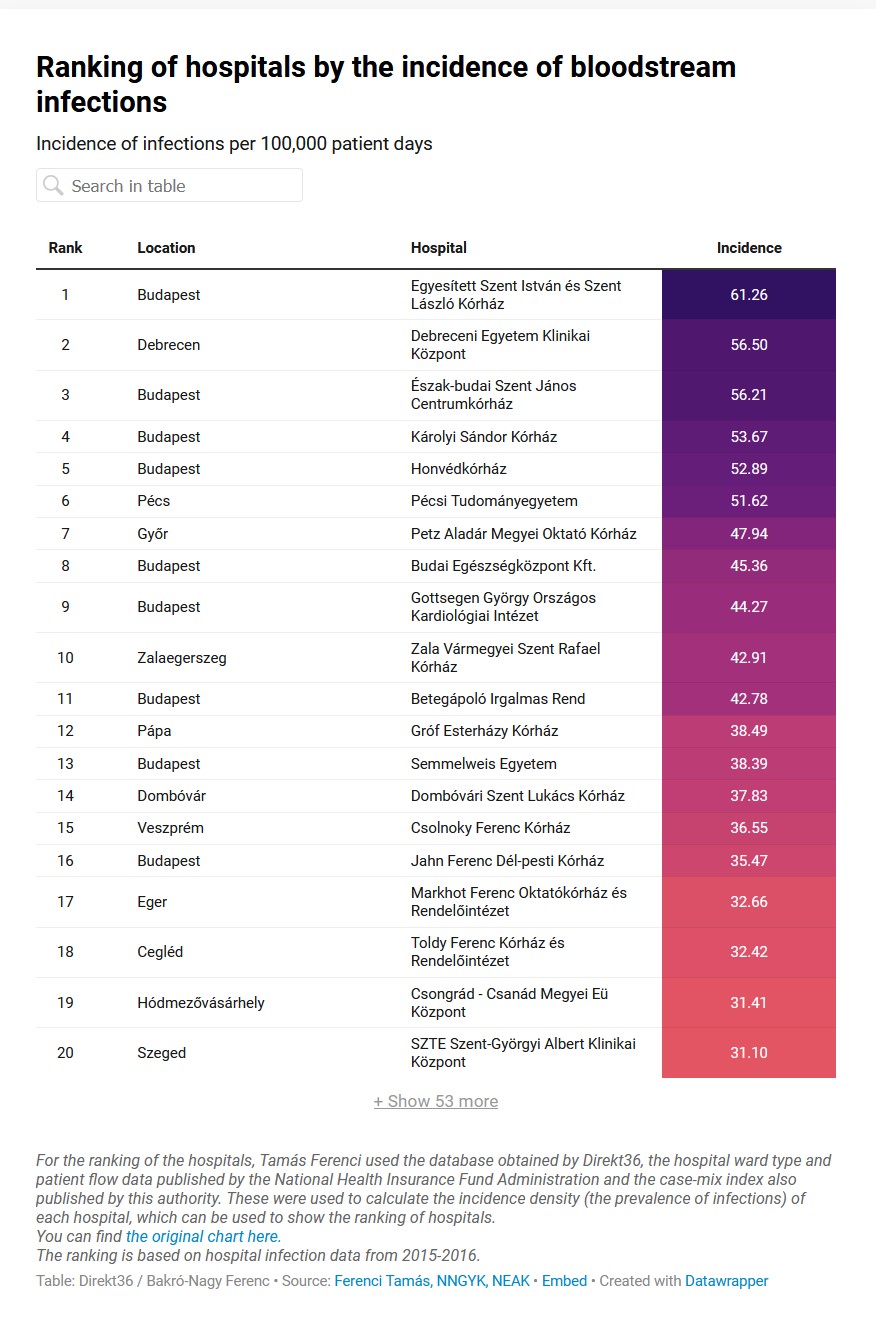

Below you can see the rankings of Hungarian hospitals by different hospital-acquired infections. At the top of the charts are the hospitals with the highest incidence rates, and at the bottom are the hospitals with the lowest. The number in the “Incidence” column shows the number of infections per 100,000 patient days, according to our calculations. You can also filter by location in the search box. (We have created three different charts as the NCPHP also collects data on different infections separately, and the numbers cannot be simply added together due to possible overlaps.)

The first chart shows infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens, by hospital. These are bacteria that are resistant to several types of strong antibiotics, which is why they are so dangerous: they are difficult to kill and can cause serious complications for already sick patients.

The second chart shows the incidence of Clostridium difficile infections. This is a common hospital-acquired infection causing severe diarrhea and, in weakened hospital inpatients, can lead to life-threatening bowel inflammation if not treated properly. Once again, the most problematic hospitals in terms of reported infections are at the top of the list.

The third graph shows the incidence of bloodstream infections. These are cases in which pathogens enter the bloodstream and cause a profoundly serious condition – sepsis or septicaemia – which is fatal in a significant proportion of cases.

If you are also interested in the ranking of each hospital department, you can also browse through that: here you can download the multidrug-resistant pathogen infections per 10 000 patients and 100 000 patient days, here the clostridium infections per 10 000 patients and 100 000 patient days and here the bloodstream infections per 10 000 patients and 100 000 patient days

And from here you can download in .xlsx format the full, original database on which our analysis is based: all the data for all reported infections, by hospital and hospital department.

Large hospital, small hospital

The charts clearly show the significant differences in the incidence of infections between hospitals, even after adjusting for biases. There is also a huge deviation in the number of cases: there is a Hungarian hospital that, for example, has not reported a single clostridium infection (and thus does not appear in the ranking), and another that has reported well over 400 in a single year. The same is true for multidrug-resistant pathogens and bloodstream infections.

For infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens, the four hospitals with the most problems are smaller institutions. In first place is Toldy Ferenc Hospital in Cegléd, where these pathogens are the most common in the whole country, according to our calculations. Markhot Ferenc Hospital in Eger and Gróf Esterházy Károly Hospital in Pápa do not compare well either. Károlyi Sándor Hospital in Budapest is among the worst in all three types of infection – in the top five.

We contacted the mentioned hospitals, but none of them answered our questions.

We did not rank how many people died from infections in each hospital. Although a significant percentage of patients who get an infection never return home, hospitals only see a link between death and infection in a small portion of cases. The assessment of what led to the death of a patient is highly subjective, with often no time to investigate the causes thoroughly, and also depends on self-reporting by hospitals.

A corpse in the bathroom

We did not have the opportunity to explore the reasons behind the performance of all hospitals individually, however, we wanted to take a closer look at some of the seemingly more problematic hospitals to see what is behind the high number of reported infections. Therefore, we selected four of the hospitals that are among the worst performers in our rankings for all three types of infection. These are Toldy Ferenc Hospital in Cegléd and Jahn Ferenc Hospital, Károlyi Sándor Hospital and Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Hospital in Budapest.

Toldy Ferenc Hospital in Cegléd is the place where – at least according to the 2015-16 data – superbugs resistant to antibiotics are infecting patients at the highest rate in the whole country. At the hospital in Cegléd, they know there is a problem. In a document uploaded to their website, which reads like a cry for help – and which sets out the hospital’s strategy for 2018-2023 – they openly admit that “the number of infections caused by special multidrug-resistant pathogens is increasing year by year, while no new antibiotic is expected to be developed to solve this problem. In the treatment of (…) infectious patients, the difficulties of isolation and the insufficient number of isolation wards are a cause for concern. The prevalence of (…) infections is also currently making medical work difficult.”

They also describe the dramatic conditions under which the staff of the institution have to provide treatment. They say that the Pesti Road facility is in conditions “reminiscent of the 1950s”, with a steadily increasing volume of patients in the four-bed surgery unit, which has long been over capacity.

“The wards are overcrowded, with 6-8 beds and we have no wards with separate water blocks (…). In summer months, the heat in the wards is unbearable. The kitchen, the laundry and the energy centre also need renovation”, says the report.

None of this helps to reduce infections. Our database shows that the surgical, intensive care, urology, cardiology and neurology departments have serious difficulties in preventing infections. For multidrug-resistant infections alone, the hospital has reported 130 cases in two years. There have been 145 cases of clostridium infections acquired in the hospital and 74 patients have received blood poisoning as a result of infections in the two years.

According to our calculations, Jahn Ferenc Dél-pesti Hospital had the highest prevalence of clostridium difficile infections in the whole country, with the most severe situation in the internal medicine department in 2015-16. The institution ranked fifth worst for multidrug-resistant pathogens. An exceptionally high amount of infections occurred in the hospital’s psychiatric ward, where out of the reported 7 cases in two years, 3 patients died from infections of MRSA and Acinetobacter baumannii pathogens.

Jahn Ferenc Hospital is struggling with the well-known problems of Budapest’s major hospitals, from outdated infrastructure to severe staff shortages and overcrowding to a lack of funding. In 2022, more than 1,500 people worked at the hospital, but 332 positions were unfilled.

Overcrowding and inadequate cleaning may have led to the 2016 national scandal following the discovery of a dead body in a visitors’ restroom at the hospital. As it turned out, the corpse had been lying there for days. The hospital launched an investigation, apologised and concluded that no one was at fault, nevertheless a number of changes were announced regarding the use of toilets, the operation of the reception service and cleaning. The cleaning service, for example, was ” partially taken back into institutional responsibility to ensure higher standards”.

This, however, did not last long, as in 2018 they contracted the external company responsible for cleaning the hospital at the time of the incident. The company won against several applicants because it significantly underbid the hospital’s estimated price: it undertook the work for 60 percent less. Price was a deciding factor of 98 percent at the time of the evaluation, while quality accounted for 2 percent.

Károlyi Sándor Hospital in Újpest has a much lower volume of patients than Jahn Ferenc, yet according to our calculations it still has one of the highest infection rates in the country: uniquely, it is among the worst five institutions in all three infection types. Within two years, the hospital has reported over a hundred cases of both clostridial and multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

There is little public information about the work being done within the walls of Károlyi Hospital, although the documents uploaded to the hospital’s website reveal a lot. Staff turnover is very high, with more than half of the hospital’s staff leaving in 2011, hundreds of people leaving over the last decade, and by 2021 the number of staff have halved compared to ten years earlier.

Károlyi Hospital has published a pessimistic report for the year 2021, which is the last available written report on their official website. In a document signed by the hospital’s Chief Financial Officer and Director, they stress that the institution has been struggling with underfunding for a decade, its IT system is outdated, and staff headcount is constantly decreasing. They added that the introduction of the 2020 law on employment in the health service has led to a further decline in staff numbers, as more staff have not signed new contracts. “Further reductions in staffing levels, which are barely adequate for current patient care activities, would put patient care at risk,” they write.

The toughest surgical and internal medicine department in the country

Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Hospital is a large institution: it serves patients from Kőbánya, Rákosmente, Monor, Gyömrő and their surrounding areas, treating 40,000 inpatients a year. Our calculations of infection incidence ranked Bajcsy as the sixth worst performing hospital in the country for the most common types of infections: for both clostridium difficile and infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Outbreaks have also occurred, for example in the department of internal medicine, where an outbreak of clostridium affected 14 people in the summer of 2015 alone (May to September). This is hardly surprising, as our calculations based on 2015-16 data show that the hospital’s internal medicine department is the second worst in the country when it comes to diarrheal infections.

Beáta Dunavölgyi, a former nurse at the hospital, recalls there were many shortcomings in the institution.

She worked full-time in the oncology department for most of the 2000s and 2010s and was deputising in the surgical department. „The surgical department was a disaster. It was hot, the air-conditioning didn’t work and they put a fan in the septic area. You can imagine what was spreading in the air”, she recalled. The cleaning, she said, was done by the hospital’s employed cleaners, who were all very elderly. “Poor Mária was pushing the cart at the age of 84 and helping to serve food, it was a disaster. There were other cleaners like that, well, they clowned around like that,” she said, referring to the fact that hospital cleaning was entrusted to people who were too old for this physically hard job.

“There were not enough rubber gloves, disinfectant, nappies, sheets, the list goes on. The rules can’t be followed like this,” said the nurse, adding that if a hospital-acquired infection had occurred, they did not investigate why it happened, they only isolated the patient using a privacy screen. “Not by placing the patient in another room, but with a screen,” she said. She also noted that no feedback or statistics were shared on how many cases of infection or even malpractice had occurred, there for they did not talk much about these things.

None of the detailed four hospitals answered Direkt36’s questions.

During Covid, things got even worse

When Covid came everything became even worse with hospital infections. Interventions for less serious cases were postponed, intensive care and covid wards became filled with infected people gasping for air, suffering from serious underlying conditions, while nurses untrained in caring for the seriously ill had to be put to work next to ventilators. In the shadow of Coronavirus the already well-known hospital-acquired infections were still spreading and taking their victims among the weakened patients in Hungary, despite all the protective suits, rubber gloves and hand disinfection.

The NCPHP’s national statistics clearly show the serious crisis that has emerged in the health sector. The incidence of all three types of infections has increased by around two and a half times compared to 2015. At least according to the number of infections reported to the NCPHP by hospitals – and this does not include the number of covid infections contracted in hospitals, which was quite common.

According to Dr. Ágnes Galgóczi, the NCPHP’s professional responsible for the issue, the number of hospital-acquired infections increased so dramatically during the coronavirus epidemic because hospitals were not prepared to isolate patients properly and the “patient material”, i.e. the condition of the people admitted to hospital changed. “Covid infection, even with healthy people, could result in long ICU stays, a major risk factor for nosocomial infections [hospital-acquired infections]”, Galgóczi said.

In contrast, in Austria the incidence of clostridium difficile has decreased during the years of Covid, which the Austrian Ministry of Health’s press spokesperson attributed to the success of the stricter measures. We have not received an answer from NCPHP as to why such a large gap developed between Hungary and Austria during the epidemic.

DISCLAIMER:

This article is a summary of articles published in October, November and December as part of Direkt36’s Semmelweis Project. The articles published so far in the series can be read in full here:

- “Washing our hands” – here is the documentary uncovering the secrets of hospital-acquired infections

In February, we published the rankings of hospitals using the latest data from 2017 to 2022

Cover art (the pictures uploaded to supporting materials):

Péter Somogyi (szarvas) / Telex

Data Visualizations:

Ferenc Bakró-Nagy / Telex

Contributors:

András Pethő – editor

Tamás Ferenci – biostatistician

OCCRP data team

Telex.hu

Documentary film:

Máté Kőrösi – director

Máté Fuchs – director